When news of the Thai government’s move to ratify the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO’s) Work in Fishing Convention (Convention 188) reached fisher associations, they came together to protest. This week, fisher associations from 22 coastal provinces of Thailand threatened to bring the country’s fishing industry to a halt by ceasing work if the government there fails to address their grievances within seven days. According to the fisher associations, Convention 188 that aims to ensure decent working conditions for fishers is too strict and ‘does not suit local conditions’.

Ranong Fishermen Association’s Vice President, Surasak Jimaphan, said that the appendix of this convention requires that “each fishing boat has one bathroom per four crewmen, a library, a fitness room and a recreational room”. Their protest is manifested in simultaneously submitted petitions by the 22 fisher associations to Prime Minister General Prayut Chan-o-cha via their provincial governors. The petition listed seven demands for the government, with the main demand to refrain from ratifying the convention and solving the labour shortage in the fishing industry.

The petition stressed the need to cater to the labour shortage by allowing illegal migrants to work in the sector for two years, registering them for fishing-related identification papers. Other demands include a mechanism for the government to take over fishing boats from those who are opting out of the industry due to the stricter regulations, as well as a demand for harmonisation of the many regulations currently governing the fishing industry in Thailand.

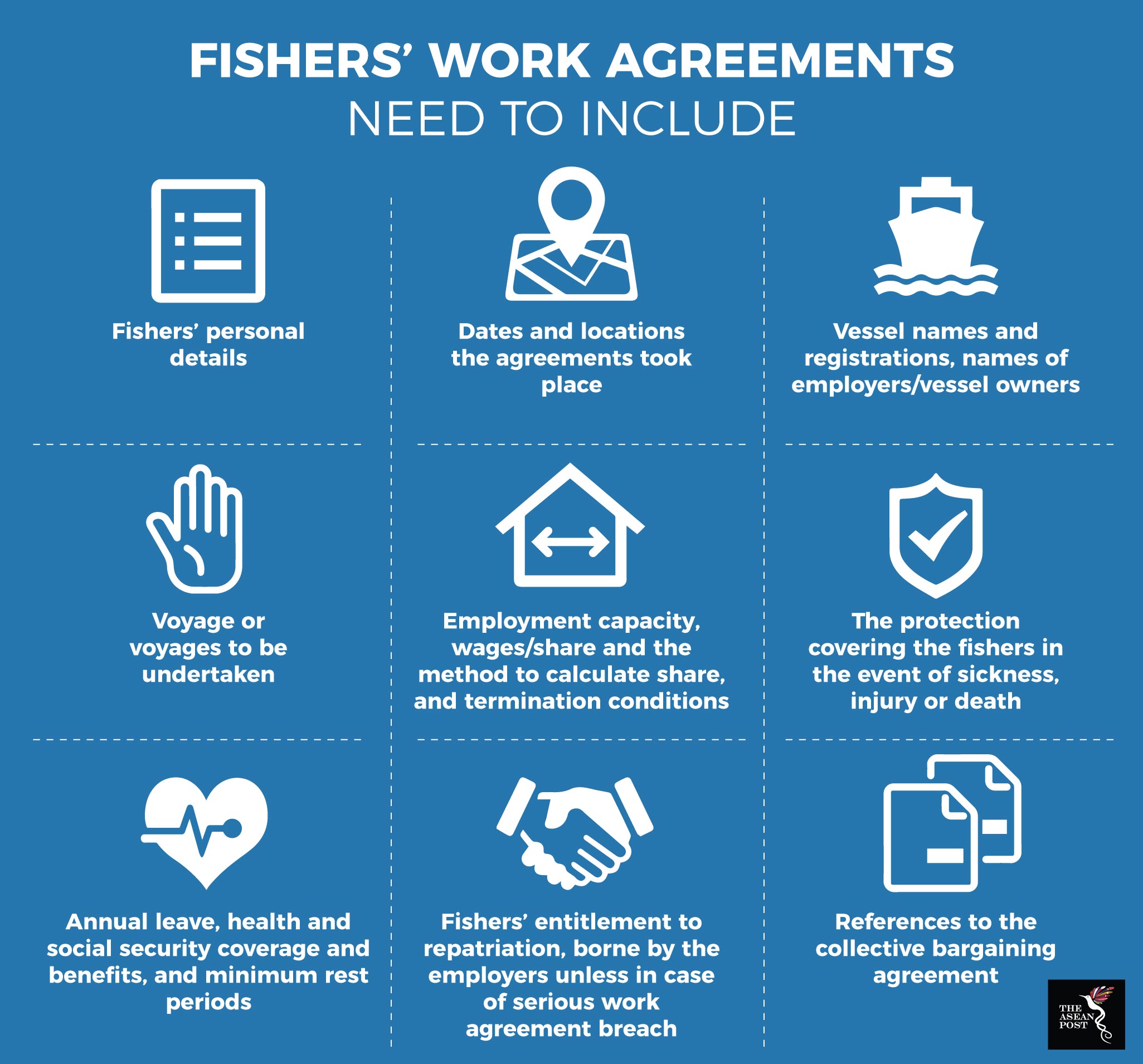

Convention 188 was adopted at the 96th International Labour Conference (ILC) of the ILO in 2007. It covers minimum requirements for work on board, conditions of service, accommodation and food, occupational safety and health protection, medical care and social security for all fishers. The convention came into force on 17 November 2017, 12 months after it was ratified by 10 countries. If the country goes ahead with its plan, Thailand will be the 11th country to ratify the convention. The other countries that have ratified the convention are Angola, Argentina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Republic of the Congo, Estonia, France, Lithuania, Morocco, Norway, and South Africa, all of which are coastal countries.

Not enough people

A survey carried out in June 2017 found that fishing operators across Thailand suffered labour shortage of up to 74,000 people. According to the survey, at the time of data collection, up to 30 percent of boats or around 4,000 fishing vessels have remained docked because of the shortage. Others have estimated the shortage to be around 42,000 to 50,000 fishers.

Recently a number of measures have been reviewed and planned to address labour shortage in the fishing industry. This include discussions held between the Thai government with its Myanmar counterparts to seek the legal immigration of labourers and easing of restrictions on foreign labour for 12 industries including the fishing industry.

Convention 188 covers not only issues relevant to the rights of 38 million fishery workers worldwide, but also addresses human trafficking, which is rife in the fishing industry. Around a third of victims of human trafficking in the Southeast Asian region were trafficked for forced labour, especially in the fishing industry in Cambodia, Indonesia and Thailand. A 2017 report by Human Rights Watch on Thailand’s fishing industry exposed forced labour and other human rights abuses, as well as poor working conditions, recruitment processes, terms of employment, and industry practices that puts migrant workers in situations vulnerable to abuses.

Source: ILO.

Dens of abuse

The report, based on interviews of 248 current and former workers in the fishing industry including 95 victims of trafficking, highlighted concerns of killings and beatings of migrant fishers, many of whom come from Myanmar and Cambodia. According to the report, accounts of human trafficking and abuses in the Thai fishing industry were the key trigger for the United States (US) Department of State’s demotion of Thailand to Tier 3 of its ranking of the world’ governments’ efforts to meet the minimum standard of the US Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA). The European Commission (EC) also threatened to ban Thai fishing products.

This galvanised the Thai government to undertake significant measures to reduce illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, as well as fulfilment of Convention 188’s requirements on member countries. In March 2018, a new order was passed by the Thai Labour Ministry requiring bank accounts for migrant fishers in the country, as well as issuance of new employment contracts, setting of minimum wage for fishers at 350 baht (US$10.50) per day, and coverage of medical and housing expenses. Thailand's Department of Fisheries is also currently drafting a law to support its readiness to ratify Convention 188. In the latest TVPA ranking, Thailand has improved its position to Tier 2. Myanmar and Lao PDR are the only two Southeast Asian countries to be ranked in Tier 3, while Malaysia is ranked in Tier 2 – Watch List for its unresolved issues in human trafficking.

In June 2018, Taiwan became the first country to have a fishing vessel detained under Convention 188 since coming into force in November 2017. Detained in Cape Town, South Africa, following complaints by the crew about working conditions, the owners are now required to take steps to rectify problems revealed by the South African Maritime Safety Authority’s (SAMSA’s) inspection, including lack of documentation, poor accommodation, insufficient food for fishers, poor safety and health conditions on board, and unseaworthiness of vessel. South Africa is a member of the convention, while Taiwan has not ratified the convention.

A cursory reading of the convention, however, revealed much misinformation including requirements on vessels. While larger vessels of 24 metres and bigger are subjected to more stringent requirements, requirements on smaller vessels are more lenient, with opportunities for customisation by the national authorities to fit into local conditions. Thailand will need to undertake more dialogues with its stakeholders, not only to localise an international set of requirements, but also to correct much of the miscommunication and misinformation.

As with many of the issues plaguing Southeast Asia, labour shortages as well as abuses and human trafficking are regional and transboundary due to porous borders and a lack of enforcement. Improved management in one key and committed country like Thailand will hopefully kick off a domino effect for further improvements in neighbouring countries.