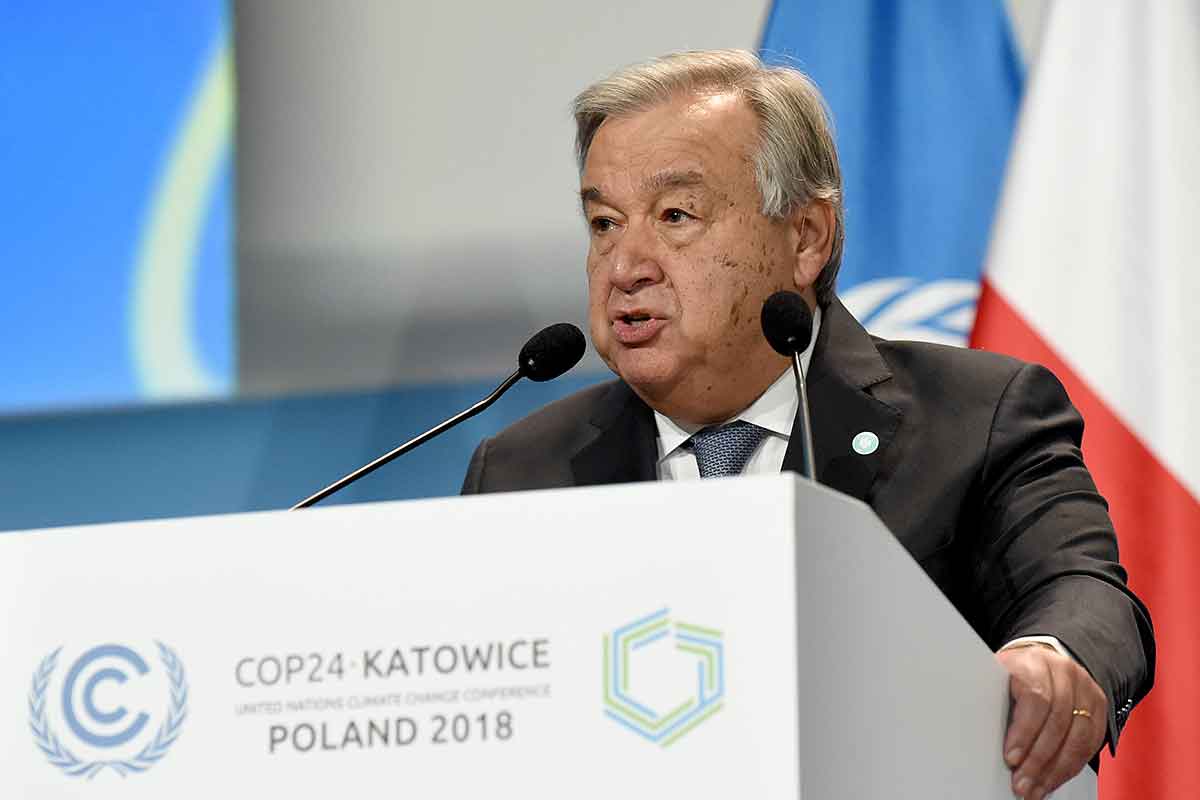

In the next two weeks, thousands of world leaders, business representatives, climate experts, activists and lobbyist, as well as indigenous and local communities, will be congregating in the Polish coal city of Katowice, for the 24th Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), or COP24. During this time, representatives of various countries, organisations and agendas will be lobbying and negotiating collective actions in addressing climate change.

In 2016, at COP21 in Paris, the conference agreed on the landmark Paris Agreement that sets the stage for further greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction and climate change adaptation. The Paris agreement which puts the onus of climate action on all countries globally, as opposed to just industrialised countries previously under the Kyoto protocol, will be implemented from 2020. The Paris Agreement set the goals of keeping global temperature rise well below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5 degrees Celsius. It also targets increasing countries’ adaptation ability and ensuring enabling climate financing.

The COP24 kicking off this week is of particular importance as it is the arena in which countries must agree on the implementation guidelines for the operationalisation of the Paris Agreement. The guidelines, known as the Paris Rulebook, is a set of tools and processes that will enable the advancement of full, fair and effective climate actions globally. Particularly, the guidance will cover rules on setting and strengthening of, as well as stocktaking, measuring and reporting on progress made on climate change mitigation, adaptation and financing against the national climate plans known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

Source: Various sources.

Ominous ticking of climate clock

In time for the start of COP24, the United Nations (UN) weather and meteorological agency or World Meteorological Organization (WMO) released a report stating record levels of GHG concentrations, threatening temperature increases of three to five degrees Celsius by century end. The WMO stressed that the global action to meet climate change targets is currently off track and heading in the wrong direction. Data from five independent global temperature monitors indicated that 2018 is on course to becoming the fourth hottest year on record.

“It is worth repeating once again that we are the first generation to fully understand climate change and the last generation to be able to do something about it,” said Petteri Taalas, WMO’s Secretary-General.

In October, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a special report on Global Warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius (SR15) that projected that the world has around 12 years before the increase in global atmospheric temperature is likely to reach 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2030.

The report warned that the magnitude of exposure, risks and impacts to natural and human systems between an increase of 1.5- and two degrees Celsius is disproportionately wide, cutting across sea-level rise, extreme weather events, habitat loss, biodiversity loss, natural resource loss, human health, livelihoods, food security, water supply, human security and economic growth.

Consideration for Southeast Asia

In setting and strengthening commitment to their respective NDCs, Southeast Asian leaders will have to come face to face with reliance on fossil fuels that dominate the region’s energy mix. Renewable energy like solar, hydro and wind constitute less than 15 percent of the region’s energy mix. Southeast Asia’s dependence on coal is of particular concern, in a time when the rest of the world is ditching it.

ASEAN leaders will also have to honestly re-evaluate their culpability in deforestation, from active involvement to tolerance, both to fulfil demand for timber and other natural resources, as well as for land to intensify commodities and food production, and urbanisation. Progress tracking for Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 15, earlier this year, found that the region has fared poorly in protecting, restorating and sustainably using forests and forested land.

Southeast Asia countries are particularly prone to natural disasters and climate-related events that also threaten to undo their hard-earned economic development. As a result, the region has experienced a resurgence in the number of hungry people mostly due to the adverse effects of climate conditions on food availability and prices. While the situation is less worrying compared to other regions, changes in climate such as temperature increase and climate variability, are undermining production of major crops like rice.

Regardless of where you stand on the climate spectrum, at the end of the day, the world will need to transition into a carbon neutral world. What’s more, we need to do this without compromising on the other sustainable development issues such as economic growth, food security, equality and biodiversity.

Related articles: