“The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was never an integration project but a sovereignty upholding project,” said Michael Vatikiotis, Regional Director for the Asia Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue at an ASEAN Roundtable held in Singapore last year.

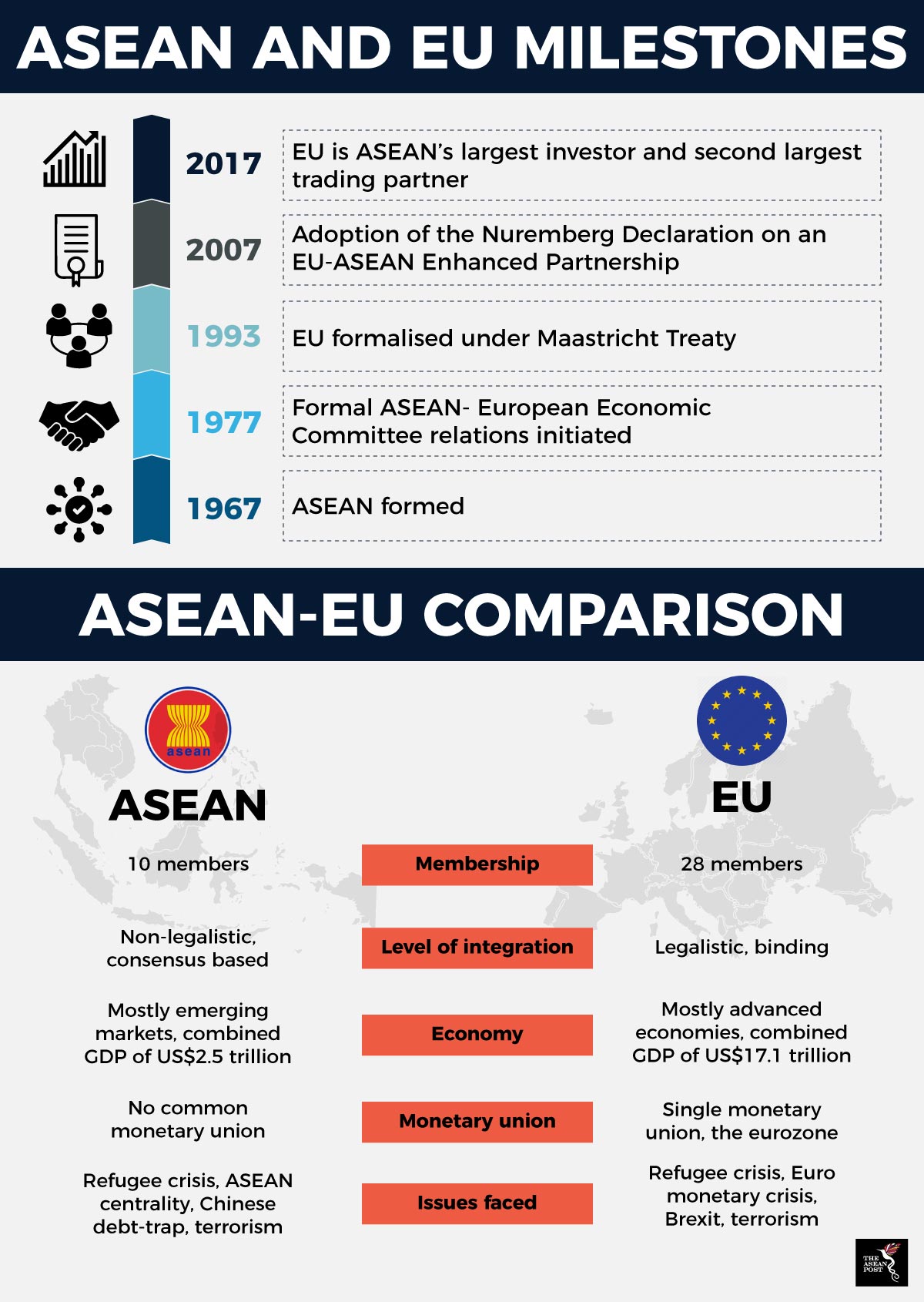

The comparison of ASEAN to the European Union (EU) is a thought exercise that many, would have no doubt contemplated for obvious reasons. Both are regional organisations representing a sizeable geography and economic clout and the EU more than ASEAN behaves as a single entity.

But most comparisons made often hold ASEAN to the standards of the EU. While such comparisons are not entirely wrong to make, the conclusion which is often drawn – that ASEAN lags behind the EU because of its failure to properly integrate politically and economically - is inherently flawed.

Which brings us back to Vatikiotis’ words and the harsh reality that the EU and ASEAN were formed for vastly different reasons.

Different formative philosophies

According to the official EU website, the union was founded “with the aim of ending the frequent and bloody wars between neighbours, which culminated in the Second World War.” The integration was aimed at minimising jingoistic tendencies amongst nations by adopting supranationalism. Under such a model, nations pooled their sovereignty into common institutions, legal frameworks and policies.

It started off with the formation of the European Coal and Steel Committee (ECSC) in 1951. The ECSC focussed on economic integration and the creation of an area of free trade for resources like coal, iron ore and steel between six nations – West Germany, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Italy. In 1957, it culminated in the signing of the Treaty of Rome, establishing the European Economic Community.

Fast forward to 1993, and the European Single Market was established – embodying the four freedoms of movement of goods, services, people and money. In 1999, the euro was adopted as the region’s currency and its management was put under the purview of the European Central Bank. Four years later in 2003, the Treaty of Lisbon was signed which amended two previous treaties and formed the constitutional framework for the EU which has since expanded to 28 nations.

ASEAN on the other hand was formed in 1967, not with the intention of Southeast Asian states pooling their sovereignty under a supranational entity but very much for the opposite of that. Where the EU was bent on dousing the flames of nationalism, ASEAN’s conception was to protect the newfound sovereignty of the newly independent Southeast Asian countries. All of ASEAN’s founding members with the exception of Thailand have been previously colonised by western powers.

ASEAN represents a project of cooperation amongst member states to protect the region from outside influence which could very well threaten the domestic affairs of its nations. In the words of former Indonesian Foreign Minister and one of the founding fathers of ASEAN, Adam Malik, ASEAN was borne out of a vision to develop “a region which can stand on its own feet, strong enough to defend itself against any negative influence from outside the region.”

At that point, during the height of the Cold War era, the imminent threat was communism which already took a foothold in the Indochina region. But in fending away the red scare and expanding ASEAN to its current 10-member configuration, the member nations adopted an informal approach to diplomacy – relying very much on a non-legalistic decision-making process.

The “ASEAN Way” as it is known today has been the subject of much envy and criticism depending on who one talks to. On the one hand, it has managed to keep the association from falling apart because member states cannot be forced into complying to any binding agreements that may be taken as a threat to that nation’s sovereignty. On the other, it’s slow process and the association’s strict adherence to the principle of non-interference can relegate it to an ineffectual talk shop with no real capacity for action.

Lessons from the European project

The paths taken since, by both the EU and ASEAN have been different. In pursuant of a more codified and legalistic manner of regionalism, the European experiment has taken quite a hit since the eurozone crisis and Brexit. ASEAN has had its fair share of criticism especially in the wake of the Rohingya humanitarian crisis in which the organisation reacted rather uninspiringly.

This doesn’t mean that parallels cannot be drawn between both organisations – although one must be mindful of the limitations that ensue.

ASEAN which has successfully survived the threat of communism in the region now has its sights on a grander vision – the establishment of the ASEAN Community based on three pillars, the ASEAN Political-Security Community, the ASEAN Economic Community and the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community. It is a sign that the association is now ready to move forward and adopt stronger rules based norms to be more relevant in the international fora.

As ASEAN trudges along this path, it risks repeating the mistakes made by the European integration project. Citizens of EU member states, have long been forced to battle an identity crisis between being a citizen of Europe or a citizen of a member state. This is largely caused by the lack of communication between the founding fathers of the EU and its citizens. It had led to a feeling of dissociation amongst Europeans who consider the union as being run by a set of political elites who fail to include the interests of ordinary citizens in its decisions.

The same problem is likely to repeat with ASEAN if such a top down strategy is applied.

Sitting on the same panel with Vatikiotis, former Philippine Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Delia Albert indicated that it is time ASEAN works on a regional community identity, after citing a study done by the ASEAN Secretariat which found that 76 percent or three out of four people lacked basic understanding of what ASEAN is.

“ASEAN urgently needs to be better understood by its people. There is a need to develop a ‘we feeling’ amongst the citizens of ASEAN. This is the challenge for the association in the coming decades,” she said.

ASEAN as we see it today shouldn’t remain like the ASEAN of 50 years ago. It must change. If it must integrate, so be it. Integration - if it is to bring about greater benefit to the region - must be based on an ASEAN brand of integration and not on the EU model.