The 2018 euphoria of the #MalaysiaBaru movement that followed the historic win of the new Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan) coalition in the 14th general election (GE14) in Malaysia, have since died down. The now one-year-old government was recently given a “Fail” grade for its overall performance, according to a recent poll by the Merdeka Centre.

The nation-wide survey of 1,200 Malaysians saw only 39 percent giving the Alliance of Hope-led government a positive ranking, down from 79 percent in 2018. The same survey showed that 46 percent of voters were not satisfied with the performance of prime minister, Dr Mahathir Mohamed. This was a marked decline compared to the 71 percent approval rating for him recorded last year.

The ruling coalition is also losing the support of Malaysians in their twenties, who previously helped secure their surprise victory last year. Then, the unemployment rate was three times the national average and with the increasing cost of living, Malaysian youth saw a need for change.

According to the Election Commission of Malaysia, youths aged 21 to 39 made up 41 percent of the 14,449,200 registered voters who cast their ballots during GE14. Satisfaction among those in this age group have since fallen by 20.6 percent.

Youth cohort

The Pew Research Center, a Washington-based think tank, refers to the youth cohort born between 1981 and 1996 (aged 23 to 38 this year), as millennials.

Millennials have been subject to a great deal of scrutiny and characterisation. They are notably seen as tech savvy, mobile and demanding in terms of work scope, with a penchant for transparency and the work-life balance ideal. A 2019 study by Deloitte found them to be ambitious but feel that their dreams have been delayed by financial and other constraints.

In Malaysia, millennials are most aptly represented by the urban Kuala Lumpur youth, whose median age is 28, with the under 15 age group being the lowest segment. These young Malaysians are united by their inability to find gainful employment, along with a pervasive disenchantment with the alleged excesses and irrelevance of a system which has failed them.

High and low-skilled jobs

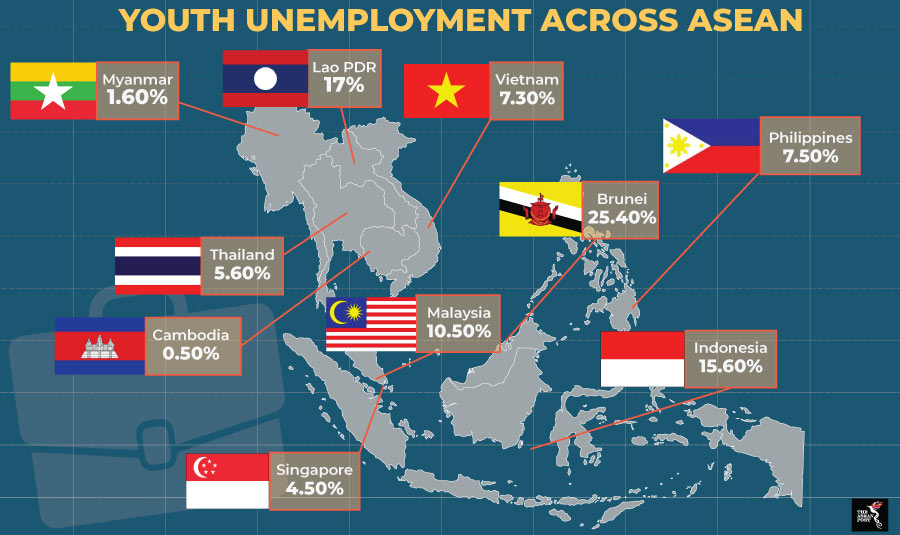

Youth unemployment in the country reached a record of 13.2 percent in 2019, according to the Economic Outlook Report issued by the finance ministry of Malaysia. The unemployment rate among those aged between 20-24 is at 11.9 percent. It is worth noting that this is not a regional high; Brunei, Lao PDR and Indonesia surpass Malaysia in this respect with rates of 25.4 percent, 17.0 percent and 15.6 percent, respectively.

A Central Bank of Malaysia (BNM) report published in March 2019, saw an average of 173,457 diploma and degree graduates entering the workforce annually. Unfortunately, the number of graduates surpassed the number of jobs available for them, at only 98,514. The lean job market is leaving Malaysian youth high and dry, with certificates but no work experience.

The BNM report also stated that Malaysia’s economy had not created sufficient high-skilled jobs to absorb the number of graduates entering the labour force. In 2018, most of the jobs created were in the unskilled and low-skilled categories, which are less preferred and not really suitable for graduates. Out of 1,473,376 job vacancies last year, 86.9 percent were for low-skilled jobs, while only 4.7 percent required any sort of tertiary education.

According to Mohd Redza Abdul Rahman, head of research at Malaysian Industrial Development Finance (MIDF), the government is planning to increase the number of skilled workers in the country’s manufacturing sector by 35 percent in 2025. He agrees that the trend favouring low-skilled jobs would affect youth unemployment, but noted the government’s efforts in promoting re-skilling and entrepreneurship in areas related to the Fourth Industrial Revolution. “We will look at whether graduates are willing to do jobs outside of their areas of studies, whether companies can provide good enough compensation (for them) to come and work in their companies,” he said.

The Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) Graduate Tracer study attributes rising youth unemployment in Kuala Lumpur and beyond to three “Ps”: poor families (low-income households), poor states (low-income states) and poor social standing (lack of access to social capital).

While there have been numerous success stories of entrepreneurs who made their fortunes despite coming from poor families, with Jack Ma as a celebrated example, data from the MOHE Graduate Tracer study shows that these cases are few and far between, with graduates from low-income households far more likely to remain unemployed.

The persistent issue of high youth unemployment is giving Malaysia’s one-year old government a headache as it grapples with a slowing global economy and the worsening US-China trade war.

Another challenge for Malaysia’s young workforce is declining monthly salaries for many fresh graduates since 2010. The BNM report also revealed a decline in the starting salaries for graduates with a basic and Master’s degree in 2018. The report noted however that the minimum wage has supported increases in salaries of lower-skilled workers in recent years.

An increase in demand for low-skilled jobs, the rising cost of education, low starting salaries and a drop in high-skilled jobs available for fresh graduates are all causes of major concern among young graduates and the government of the day. Failure to deal with this situation could see Malaysia left behind as its neighbours surge ahead to embrace the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Related articles: