She is Thai, he is a Malaysian. She is 11, he is 41. She used to play with one of his children from another marriage. He has two other wives. He was her Quran teacher. She says she loves him and doesn’t want a divorce. He says their marriage is not driven by lust because he knew he would make her his wife years ago – when she was just seven.

They say they have been ‘in love’ for three years. He says they will not consummate their marriage until she turns 16. In the mean time she will remain with her parents. She has never been to school. Her family lives in poverty and are rubber tappers. Her husband is a rubber trader. Her parents sell their rubber to the man she now calls husband. He has also helped them financially over the years. She has never been to school. She didn’t have a chance.

As both of them are Muslims, their marriage falls under the purview of the Syariah or religious law. Under the Syariah law in Malaysia and Thailand, the minimum legal age for marriage for girls is 16 years and 18 years, respectively. But in Malaysia, marriages at a younger age are possible with permission from the Syariah Court. Thailand says they haven’t registered the marriage, Malaysia hasn’t either. It was later revealed that they were married by an imam (Muslim religious leader) in Sungai Kolok district of Narathiwat province in southern Thailand, without the permission of the state but with the girl’s parents’ blessing. The Gua Musang Syariah Court in Kelantan, Malaysia, fined the man RM1,800 (US$442) for marrying a minor without prior consent and for engaging in polygamy without permission from his existing spouse.

This is the story of one girl. Sadly, there are millions like her. Some cases involve underage girls marrying boys of a similar age while some cases involve marriage with much older men. Many of these girls are married against their will.

Global scourge

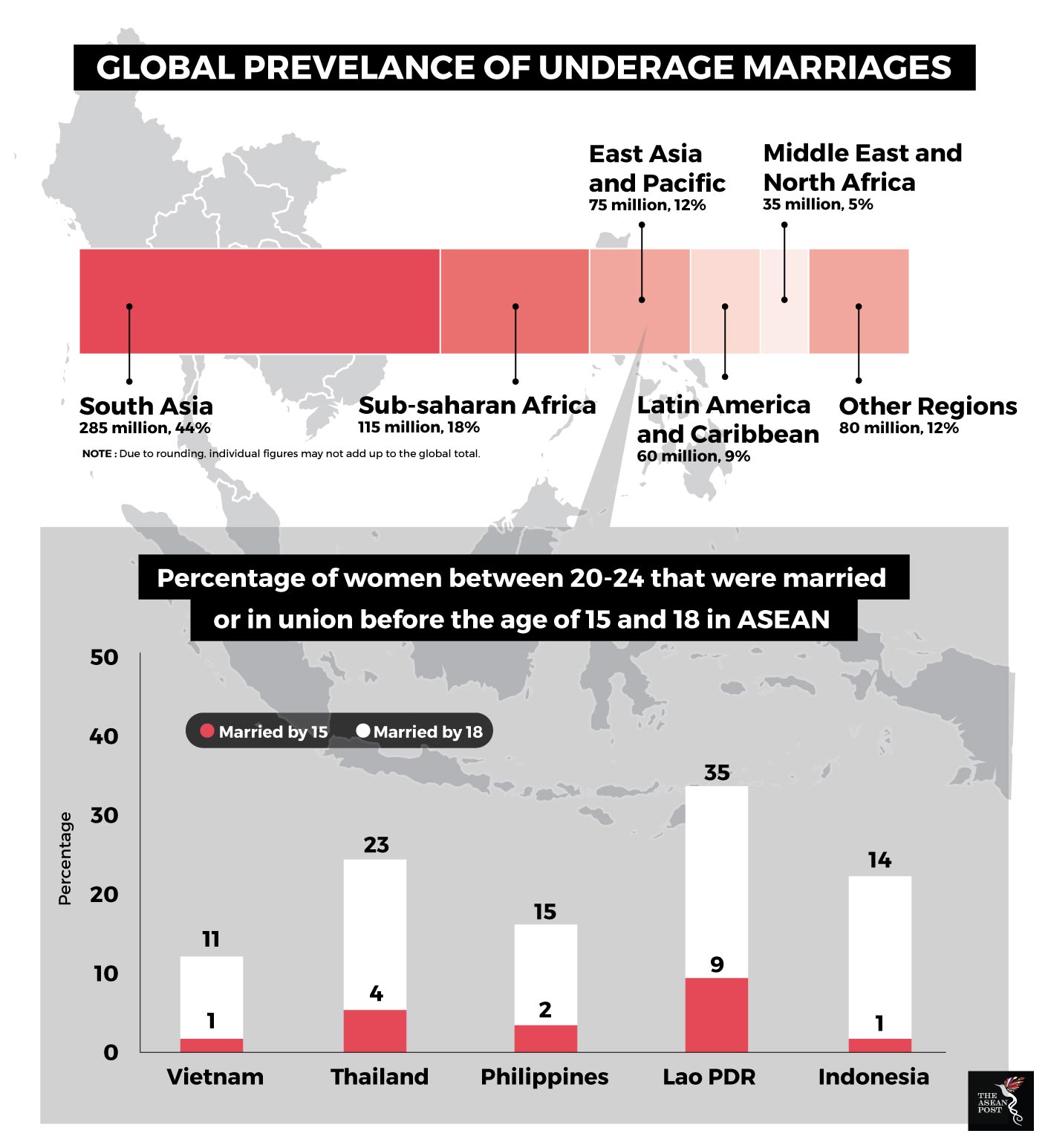

A report on latest trends and future prospects of child marriages by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) puts the number of girls and women alive today that were married before their eighteenth birthday at 650 million. 44 percent of this number include 285 million women living in South Asian countries like India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan and Maldives. This is followed by Sub-Saharan Africa (115 million, 18 percent), East Asia and Pacific (75 million, 12 percent), Latin America and the Caribbean (60 million, 9 percent), and Middle East and North Africa (35 million, 5 percent). Other regions accounted for 80 million or 12 percent of married women under the age of 18.

Among ASEAN countries, UNICEF data shows the highest proportion of child marriages occur in Lao PDR, with nine percent of women there aged 20-24 years old who were married or in union before the age of 15 and 35 percent of women aged 20-24 years old who were married or in union before they reached 18 years of age. Lao PDR is ranked 24th in the order of countries with highest prevalence of child marriages. This is followed by Thailand at four and 23 percent, the Philippines at two and 15 percent, Indonesia at one and 14 percent, and Vietnam at one and 11 percent.

Source: UNICEF

“Child marriage is an egregious violation of every child’s right to reach her or his full potential. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) enshrine a target to eliminate this practice by 2030.

The practice of child marriage has continued to decline around the world. During the past decade, the proportion of young women who were married as children decreased by 15 percent, from one in four (25%) to approximately one in five (21%).”

“While the global reduction in child marriage is to be celebrated, no region is on track to meet the SDG target of eliminating this harmful practice by 2030. In order to meet the target of elimination by 2030, global progress would need to be 12 times faster than the rate observed over the past decade,” the report stated.

Reports that analyse data from national surveys such as the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) and Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) record no data for Malaysia, Brunei or Singapore. However, a 2018 working paper from the National University of Malaysia for UNICEF Malaysia quoted data on 15,000 girls who were married before the age of 15 as of October 2010. According to the working paper, there were 5,215 cases of married, non-Muslim female children (16 to 18 years old) from 2005 to October 2015. The document also quoted data from the Malaysian Department of Syariah Judiciary that recorded 6,584 cases of marriage involving Muslim children from 2011 to October 2016. The working paper also quoted the 2010 Census on Indigenous People that reported 196 married children out of 63,883 married couples in the community that year.

What is more worrying is the fact that obtaining accurate data in most countries on the incidence of child marriage is difficult due to under-reporting, in particular due to unregistered or unofficial marriages, as well as customary marriages. This includes the case in Malaysia where the public were only made aware of the marriage when the man’s second wife complained on Facebook.

Not the full story

Most worrying are the unknown statistics on refugees and stateless children that are not captured. There have been reports of Rohingya girls escaping persecution, violence and apartheid-like conditions in Rakhine, only to be sold into marriage to Rohingya men in neighbouring countries. Some were even forced to marry their own human traffickers.

When reported, these cases are usually met with outrage from the public.

At the very heart of the problem is poverty as well as inadequate healthcare, a lack of education, poor living standards, and a lack of empowerment. UNICEF ranks countries around the world with the highest rates of child marriages. These include Niger (76 percent), Central African Republic (68 percent), Chad (67 percent), Bangladesh (59 percent), Burkina Faso (52 percent), Mali (52 percent), South Sudan (52 percent), Guinea (51 percent), Mozambique (48 percent), Somalia (45 percent), Nigeria (44 percent), Malawi (42 percent), Eritrea (41 percent), Madagascar (41 percent), Ethiopia (40 percent), Nepal (40 percent), Uganda (40 percent), Sierra Leone (39 percent), Democratic Republic of Congo (37 percent), and Mauritania (37 percent). 18 of them are from the African region and two are from Asia. In terms of religion, these countries are divided right down the middle with eight being majority Christian and seven majority Muslim. Three countries have equal followers of Islam and Christianity. Madagascar has a majority of traditional belief followers while Nepal is majority Hindu. Five are war-torn countries.

A shared commonality is the fact that all of these countries reside at the bottom of the Human Development Index (HDI) rankings. The HDI is a composite index of life expectancy, education, and per capita income indicators. A country gets a higher HDI score when its citizens’ average lifespan, education levels and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita is higher. Somalia, a country trapped in a protracted crisis, is not ranked as data for the country is unavailable. However, Somalia’s gross national income per capita is US$294, the lowest out of almost 200 countries ranked. Besides Nepal and Bangladesh, all 18 countries are categorised within the low human development tier. In these countries, the mean years of schooling for their citizens ranges between 6.1 to 1.4 years, while life expectancy goes as low as 51.3 years.

Human development enlarges people’s choices. The higher the human development level, the more control one has over his/her life choices. This may range from small choices like what to wear and which brand of smartphone to choose, to larger more serious issues like career path choice or choosing a life partner. With universal access to education, proper healthcare and the eradication of poverty, perhaps then, stories like that of the 11-year old girl from Malaysia will be only found in history books.