Some years ago, I replaced my 36-inch television – grudgingly. I only had it for a little over 24 months. The Helpline diagnosed it to be a problem with the motherboard, which would cost more to fix than buying a brand new television with better sound, a sharper picture, et cetera et cetera. Recently, my Bluetooth speaker went blip. Same advice – go for the latest model.

It seems ridiculous to discard an entire product because one part is broken. Yet finding a repair shop these days is difficult. Perhaps because technology is advancing so rapidly, there is no worth in repairing a model that will shortly become obsolete. Perhaps because raw materials are in abundance, there is no urgency to conserve. If this is the belief, then everything we produce invariably becomes a disposable.

Growing up, we lived on a modest income. Mum would turn leftover roast into stew. Mum loathed to throw food away. Years later, I witnessed the same prudence in my friend, Jasmine, who reconstructed her wedding gown into a cocktail dress, and gifted it to her daughter. Jaz did well – the dress looked fresh and “haute” on the young bride.

How many of us reuse and recycle? We are conditioned to think “linear”. We take resources, we turn them into products, we throw them away.

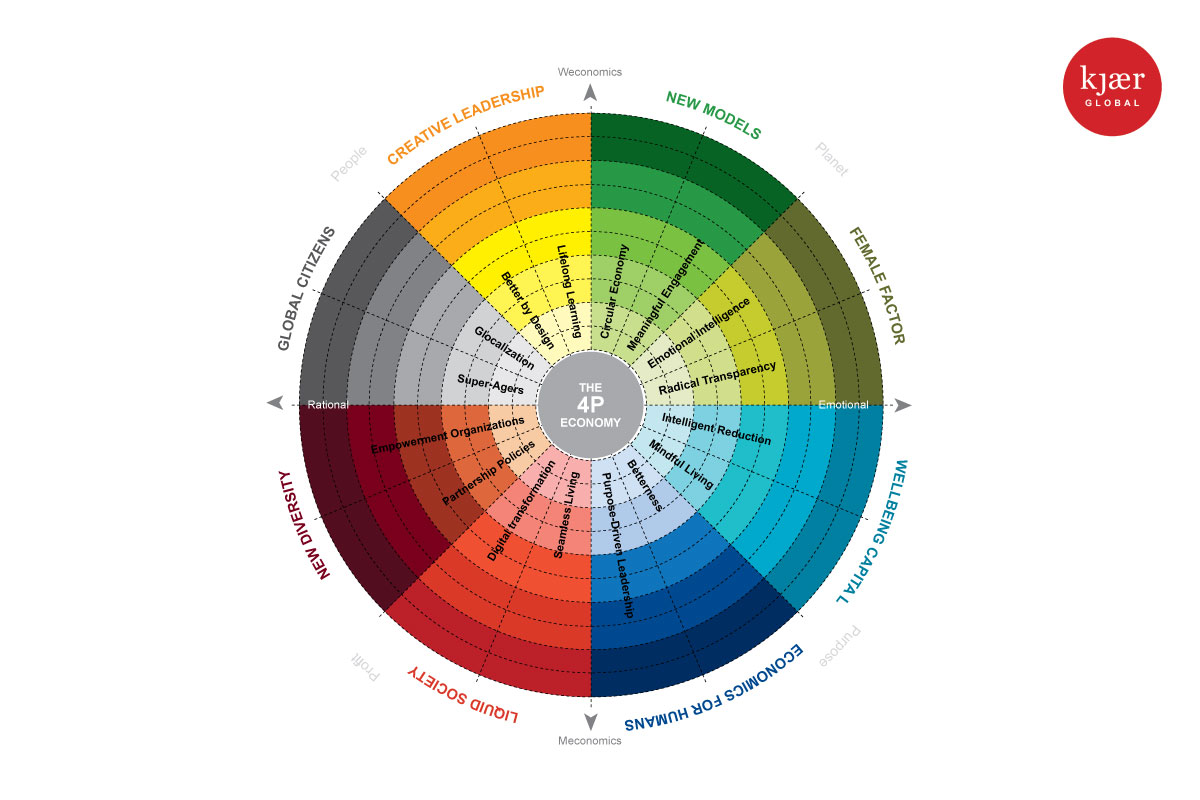

In a “circular” economy, there is little waste. The model advocates “upcycling”, challenging inventors to design products that can be deconstructed down to their raw elements when they reach end of life, these elements to become inputs to the next or new products. A company in Singapore uses a specially formulated rubber component in their tyres that can easily be separated and recycled into footwear.

The circular model also argues the case that consumers buy hardware when what they really want is service. We procure mobile phones and lightbulbs, yet, what we desire is the service of communication and illumination. Spotify understands that consumers wish for the service of music with no requirement for owning CDs.

“Circularists” would contend that I should have been offered to lease instead of buy a television, and when it no longer worked, return it to the same vendor for deconstruction in exchange for a working model. A boutique in Amsterdam rents out jeans. At the end of the lease, the customer gets a new pair, and the returned one is recycled into cotton for weaving again.

In theory, the restorative economic model is logical. In practice, it has encountered some resistance – like, implementing ride hailing in some countries. Making the circular model work requires clever “no alternative” policies (levy fines, offer incentives etc) to help markets believe, and witness, that the practice of conservation, preservation, and prudence makes good business sense.

As I write this, ASEAN heads have just concluded their 31st ASEAN Summit in Manila. The projection is by 2030, ASEAN as a single economy will grow from its current seventh to the fourth largest in the world. Marking its 50th anniversary, ASEAN’s collective appetite for higher living standards and resources can only increase. And with that, ever-growing volumes of waste.

ASEAN is the fourth largest exporting region in the world, feeding textiles, electronics, automotive parts, raw materials, etc to developed nations and member countries. No doubt, leaders at the Summit negotiated the best deals on trade and materials for their respective countries. Fast forward 30 years, how much of those materials will remain available, scientists have lamented.

Notwithstanding the warnings, it will be challenging to convert markets today on the promise of a leaner tomorrow, particularly for countries that consider it economically rational to opt for the cheaper “take-make-dispose” versus the more expensive upcycling.

ASEAN as an integrated economy is poised to beat the odds. It has direct access to many top global companies headquartered in the region. Its 600 million-strong population are relatively youthful, and of diverse ethnic backgrounds, cultures, religions and value systems.

ASEAN might want to take the dare of the circular economy, leverage its creative youth for design and research, draw on the natural resolve of women to save and salvage, and condition its markets for responsible consumption. It has, after all, the eco-system for trial and success.

Rowina Ghazali Seth spent 30 years in the Oil & Gas industry and is a jazz enthusiast.

Recommended stories: