Oceans cover more than 70 percent of the earth’s surface and provide for the coastal communities that accounts for 35 percent of the global population. ASEAN’s 173,000 kilometres of shorelines has at least 500 million coastal people living within 30 kilometres of the reef. This proximity has made nearshore ecosystems vulnerable to habitat change from destructive human activities such as overexploitation, pollution, ineffective governance and coastal development. Climate change is also threatening the reef’s ecosystem.

There are 5.1 million hectares of coral reefs in Indonesia, of which 65 percent face extinction due to destructive fishing practices. Protecting marine life and the reefs indirectly protect the fish. If coral reefs die, so do the fish. Scientists have predicted 90 percent of coral reefs will be in extinction by 2030. The reefs also protect coastlines from waves, storms and floods.

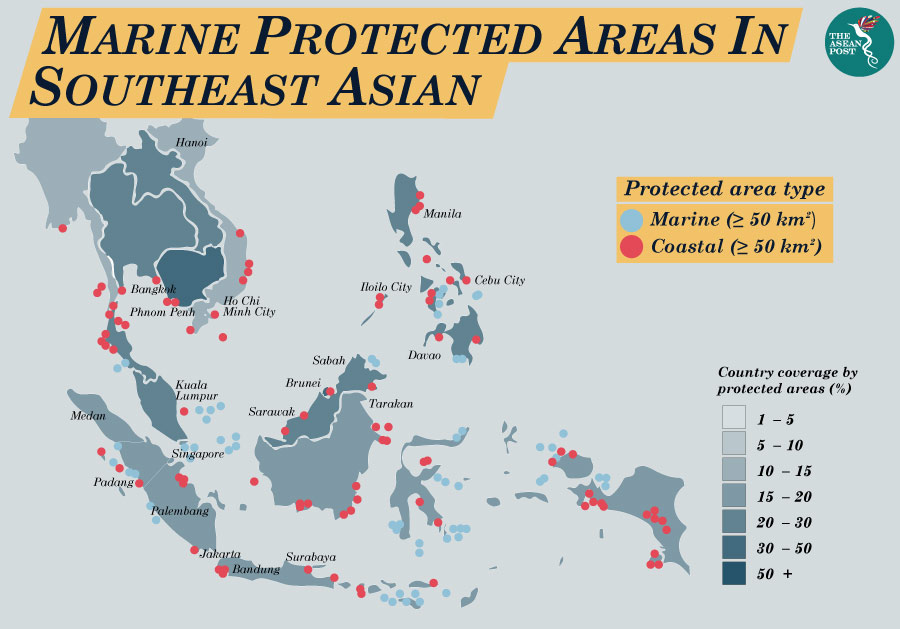

The United Nation (UN) Environment and its partners have promoted the implementation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) to revive the biodiversity of reefs and to secure fish populations, ensuring wide-ranging benefits to people and societies. MPAs are categorised into extractive zones, multipurpose zones and no-take zones.

MPAs can help maintain and restore the health of ocean and coastal ecosystems says UN Environment Ocean’s expert, Ole Vestergaard. “In the long run, using the ocean in a sustainable way is our best option for preserving the abundance of resources that we take from them – the recently announced UN Decade of Ecosystem Restoration 2021-2030 should help provide impetus to protection efforts.”

The last 15 years have seen a 25 percent increase in designated MPAs. There are currently 14,882 protected areas in 2019, covering 7.6 percent of global oceans. The Sustainable Development Goal 14 (SDG14) targets a 10 percent increase of MPAs by 2020.

Opposing camps

MPAs are helping the coasts, estuaries and seas in many ASEAN countries, however, questions have been raised on the selection of areas and whether quotas are filled to achieve targets of conservation benefits.

Opposing camps to the system exist. The Nature Protectionists (NPs) assert that fisheries are in crisis, and conventional fisheries management has failed. Whereas the Social Conservationists (SCs) believe that the crisis has been overblown, and conventional management is doing its job at improving fish stocks. The NPs see the importance of preserving vulnerable species, while SCs believe the benefits of sustainable development outweigh the value of biodiversity. The critique is that while MPAs preserve reef habitats they do not necessarily benefit fisheries.

Though in many cases, traditional fisheries management approaches were not successful in preventing overfishing and dwindling fish stocks. An example of this is the continuation of the coral trade for aquariums at Pulau Bidong island in the state of Terengganu in Malaysia, despite the declining levels of living corals in its waters.

However, Seraya Besar in Indonesia has been able to reap the benefits of its MPA. Fish stocks have been boosted to 1,000 fish per 100 square metres. Together with Coral Guardian, a non-profit conservation organisation, natural reefs have begun to prosper, with bigger fish such as groupers, trigger and butterfly-fish returning to the area.

MPAs are central in efforts to protect the world’s sea life and biodiverse habitats. But, small teams of rangers and managers are understaffed, poorly equipped without basic information on damaging activities that are taking place.

Involvement of locals

To be more effective, MPAs needs strong governance that promotes a sense of stewardship to demonstrate the social, economic and environmental benefits for communities.

Collaboration with local fisher communities is imperative. Martin Colognoli, Coral Guardian’s Co-founder and Scientific Director gave credit to Seraya Besar’s fisher communities for their efforts with the project, which include construction and deployment of concrete-iron cage structures that hold the newly implanted corals, as well as the deployment of ecological and social surveys. They also prevented further fishing and boats anchoring in the area during the restoration process.

“We believe that effective biodiversity protection requires the involvement of local populations, their participation in its conservation and their capacity to sustainably manage the ecosystems on which they depend,” said Colognoli.

In order for the MPA strategy to succeed, it must be managed effectively. The Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool (SMART) was developed with the collaboration of nine global conservation organisations to improve the performance of protected areas, both on land and at sea. SMART eases the process of collection, storing, communicating and analysing risks. It has been used in at least 600 sites across 55 countries.

MPAs are a key strategy for simultaneously protecting marine biodiversity and supporting coastal livelihoods. And it is important that everyone understands that protecting the ocean is a collective responsibility.

Related articles: