Item 10 on the United Nations’ (UN) list of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) is to reduce inequality by 2030. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) called income and gender inequality a growing global problem. The World Economic Forum (WEF) estimated it would take 217 years for women to close the gender gap in employment and pay.

To nudge governments forward and achieve this goal quicker, international non-profit groups Development Finance International (DFI) and Oxfam decided to publish report cards on 152 countries’ commitment and progress in reducing the gap between the rich and poor.

Oxfam has said that inequality has reached crisis levels. The world’s richest one percent raked in 80 percent of the wealth created between mid-2016 and mid-2017, while the bottom half of the world’s population did not increase their wealth. This is far more dramatic than the UNDP’s estimates that the world’s richest 10 percent earned up to 40 percent of the total global income while the poorest 10 percent only earned between two and seven percent.

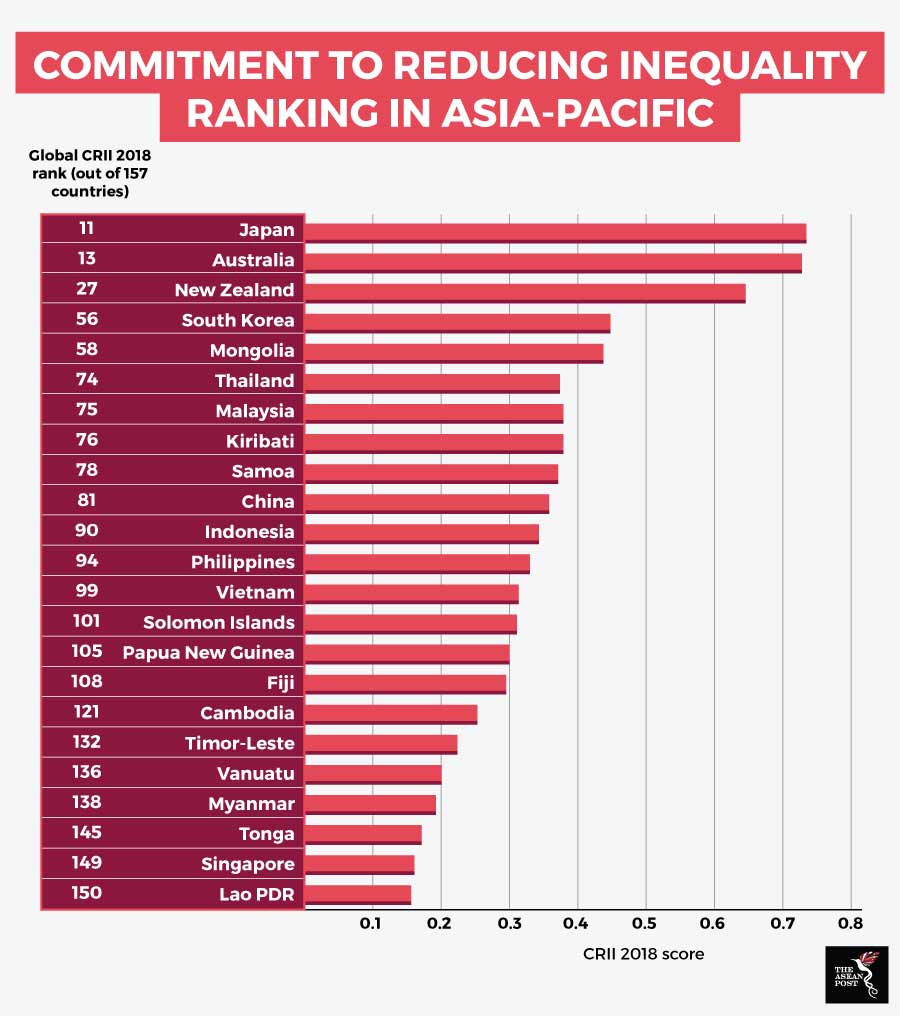

For the Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index (CRII) 2018, DFI and Oxfam used a database of indicators covering 157 countries. The indicators measure government action on social spending, tax and labour rights - three keys areas considered critical for reducing inequality.

Progressive taxation – imposing higher taxes for higher earners – is seen as a way to fund healthcare and other social programs that can help reduce the rich-poor gap. Countries that do not impose such taxes or have very low tax rates typically obtain lower scores.

“Children are dying from preventable diseases because of a lack of healthcare funding, while rich corporations and individuals dodge billions of dollars in tax,” said Winnie Byanyima, Oxfam’s executive director.

Furthermore, countries with very low tax rates tend to be tax havens for corporations and individuals to avoid and evade taxes.

Other indicators used in the CRII include minimum wages and the enactment of laws against sexual harassment and rape.

Favourable scores for some

DFI and Oxfam recently released the second edition of the CRII and gave favourable scores to Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Myanmar for improvements over the previous year’s report.

Thailand is ranked highest among ASEAN member states, sixth in the Asia-Pacific region, and 74th in the world. The kingdom was praised for setting aside half its national budget for education, health and social protection. It also allocates a high proportion on housing.

Malaysia sits second among ASEAN countries, rising dramatically to seventh in Asia-Pacific (from 15th previously) and 75th in the world (from 106). DFI-Oxfam commended Malaysia for increasing the minimum wage in the country by more than 20 percent of per capita gross domestic product (GDP). countries

Indonesia comes in third place, 11th in Asia-Pacific (from 14th) and 90th in the world (from 101st). Its scores improved due to efforts to increase the minimum wage (which rose nine percent) and to equalise wages across the country, especially in the poorer regions.

Oxfam noted that at 11 percent, Indonesia has one of the lowest tax collection rates in the world, despite its population being richer in terms of per capita income. It suggested that more could be done to raise funds for healthcare. “If Indonesia increased the amount of tax it collected by just two percent of GDP, it could more than double spending on health”.

Fourth-placed Philippines is 12th in the Asia-Pacific region (from 17th) and 94th globally (from 114th). Its ascent can be attributed to raising income taxes and efforts to increase maternity leave from 18 to 26 weeks.

Vietnam slipped in all rankings for making no improvements in its labour laws to narrow the inequality gap.

Cambodia dropped one spot in Asia-Pacific to 17th and fell to 121 (from 111) in the world, despite increasing the minimum threshold for paying value-added tax (VAT) which helps small traders by exempting them. Cambodia’s CRII scores declined because of its low social spending and for implementing minimum wages only for specific sectors.

Source: DFI and Oxfam

Source: DFI and Oxfam

Oxfam noted that women may still be trapped in a cycle of poverty although they receive minimum wages and work overtime. In many countries, minimum wages do not equate to wages needed for living expenses. A 2013 study found that wages in garment-making countries like Cambodia declined in real value by 14.6 percent between 2001 and 2011. Around 80 percent of garment sector workers are women, Oxfam said.

Myanmar improved its ranking from bottom to seventh in ASEAN, 20th in Asia-Pacific (from 23rd) and 138th (from 150th) in the world. This was aided by an increase in spending on housing.

Lao PDR replaced Myanmar in bottom spot on the ASEAN list, falling to 23rd in Asia-Pacific (from 20th) and 150th (from 134th) in the world. Although it increased spending on health, Lao PDR’s lack of progress in improving labour laws dragged it further down.

Singapore’s ranking slips

Singapore had the biggest drop in the CRII, falling from third in ASEAN to eighth, 22nd (from 12th) in Asia-Pacific, and 149th (from 86th) globally, sitting in the bottom 10th. Oxfam said this was due to Singapore introducing "harmful tax practices." Personal income tax was raised by two percent but the maximum rate for high earners remains capped at 22 percent.

Singapore also lost points for its relatively low-level of public social spending. Only 39 percent of its national budget goes towards education, health and social protection. It also lacks anti-discrimination laws for women, has inadequate rape and sexual harassment laws, and only stipulates minimum wages for cleaners and security guards.

Clearly irked by this unflattering assessment, Singapore’s Minister for Social and Family Development, Desmond Lee, dismissed the report as a “collection of ideologically driven indicators” that ignores “real outcomes.”

“In Oxfam’s view, Singapore’s biggest failing is our tax rates, which are not punitive enough,” he said in a statement. “Yes, the income tax burden on Singaporeans is low. Almost half the population do not pay any income tax. Yet they benefit more than proportionately from the high quality of infrastructure and social support that the state provides.”

He also pointed to the performance of Singapore students, the high ranking of Singapore’s healthcare system, long life expectancy and low infant mortality as evidence that debunk the ranking. Although the island-state has no minimum wage in place, it provides income support for low-income workers, upskilling schemes and a progressive wage model for certain low-paying jobs.

“That we achieved all of this with lower taxes and spending than most countries is to Singapore’s credit rather than discredit,” he said.

Efforts to reduce inequality should not be a competition and the CRII is just that, an indicator. It encourages countries to redouble their efforts to address income inequality and perhaps, in Singapore’s case, gender as well.

Related articles: