A week ago, Malaysians were shocked with news of the gruesome death of 11-year old Cambodian girl Siti Masyitah Ibrahim. The girl had been missing since 30 January, and her body was found a mere three kilometres away from her home. Her hands had been tied behind her back, she had been decapitated, and – perhaps most sinister of all - some of her internal organs had been removed.

The ASEAN Post would like to make it clear from the beginning of this article that Malaysian police have denied any elements of organ harvesting and have stated that there was, instead, a possibility that the body's condition was caused by wild animals and possibly exposure. The police also suspect revenge as a possible motive for the child’s murder.

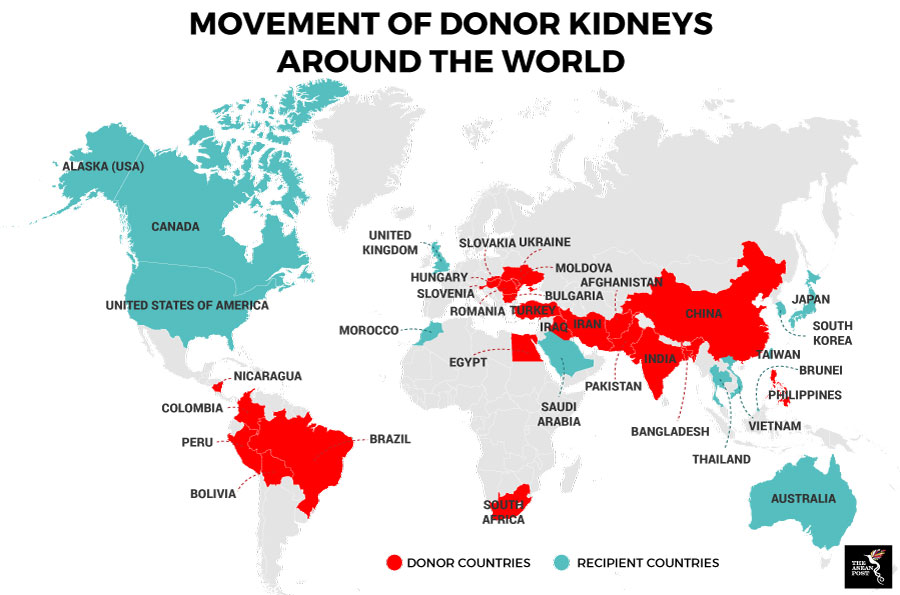

The case is both stomach-turning and heart-wrenching. Even if the disappearance of her organs were due to more natural causes, the case does at least bring some attention to the macabre - yet globalised - organ trafficking trade existing not only in Malaysia, but in the rest of the region as well. This sinister trade often involves multiple countries in a global network.

Globalised trade

While organ transplants save thousands of lives every year, health experts point out that the demand far outweighs supply. This phenomenon has unfortunately created the avenue for the illicit trade in human organs.

According to a 2015 report from the European Parliament's Directorate-General for External Policies titled "Trafficking in human organs", since 2000, organ trafficking has spread from mainly South and Southeast Asian countries to Latin America, North America and other regions afflicted by poverty and political instability.

The document cited a World Health Organization (WHO) 2007 estimate that five to 10 percent of all kidney and liver transplants performed globally were conducted with illicitly obtained organs.

The fact that a 2015 document cites a 2007 estimate could be due to the difficulty in getting new data on the subject. This was reiterated by Francais Delmonico, a professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School, last year when he said that the illicit nature of the trade made it difficult to measure its impact, but that global inequality made the poor "ripe for exploitation".

Source: Coalition for Organ Failure Solutions, Organs Watch, European Society for Organ Transplantation

“People who are rich are able to buy organs and it’s the poor who end up being the source of these organs. You can go to a country such as India and get an organ there (illegally) or you could get the donor coming to India from Africa and do the transplantation there. It happens every day. The extreme aspect of this picture is that this process becomes even more abusive.”

According to END IT Alabama (a human trafficking task force), human trafficking is a very lucrative business. It is estimated to be worth US$32 billion (RM127 billion) annually, second only to the drug trade. The task force says it would only be a matter of time before human trafficking surpasses the drug trade.

Unfortunately, like Delmonico says, it is the poor who end up becoming the victims and that includes the poor in ASEAN.

In 2016, Australian-based ABC News found evidence of organ trafficking in West Java, Indonesia, where residents had sold their kidneys. According to ABC News, eight residents of a local village had sold their organs for around US$7,500 each.

Senior Police Commissioner Umar Fana Surya was in charge of the investigation into the organ trafficking trade. He was reported as saying that 30 victims had come forward, and three suspected brokers had been arrested, adding that kidney recipients paid as much as US$30,000 each but the broker received most of the money.

In August 2014, media reports emerged about new alleged organ trafficking cases at a military hospital in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Phnom Penh’s deputy police chief Prum Sonthor, who investigated the case, said it was a training exercise between Chinese and Cambodian doctors, using voluntary Vietnamese donors and patients. But he was unable to rule out whether money changed hands.

That same year, reports emerged of an 18-year-old Cambodian who had undergone surgery in a hospital in Thailand to remove and subsequently sell his kidney. In 2014, in Thailand alone, there were 4,321 people on the organ waiting list up until August. Deceased donors’ organs accounted for around half of the 581 kidneys transplanted last year, according to the Thai Red Cross Organ Donation Centre (ODC).

Strict rules needed

In June 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) called on governments around the world to do more to stop the “thousands of organs” being trafficked every year, including strengthening legislation and improving regulations for hospitals.

Delmonico claims that only a handful of countries including the United States (US), Spain and Sweden had dedicated laws for organ donation.

"In the transplantation sphere, governments should be monitoring who are the donors, who can be the recipients. At the moment, this transparency doesn’t exist," he said.

The organ trade, like human trafficking, is often a globalised operation involving several different countries. If legislation and regulation are truly the way to go in addressing this issue, then ASEAN should come together and see what it can do as a bloc to combat this scourge.

Related articles: