Last July, The National Legislative Assembly in Thailand voted unanimously to approve, with binding effect, the country’s 20-year National Strategy. The National Strategy overlooks six strategic areas: security, competitiveness enhancement, human resource development, social equality, green growth and rebalancing and public sector development.

All government agencies and public organisations must comply with the master plans outlined by a drafting panel and approved by the National Strategy Committee and then the cabinet. Budget allocations must also be in line with them. Any policy proposed by a political party, government policy statement or budget allocations must be within the national strategic framework. Non-compliance from government agencies could mean its chief would face suspension from public office or removal from position, expulsion or a jail term.

The National Strategy Committee comprises of the prime minister; speakers of the Houses and the Senate; a deputy prime minister or minister; Defence permanent secretary; chiefs of the armed forces, army, navy, air force and police; secretary general of the National Security Council; chairman of the National Economic and Social Development Board; heads of the Board of Trade, Federation of Thai Industries, Tourism Council of Thailand and Thai Bankers Association.

The question is whether such a strategy allows for the military junta to hold future elected leaders to ransom for the next 20 years.

Source: Various

Source: Various

Politicians cry foul

Just recently, political parties complained about the 20-year plan saying the rules would prevent them from initiating policy platforms or reformist agendas. Key Pheu Thai Party member Chaturon Chaisang slammed the regime's 20-year national strategy and reform plans, saying the long-term strategic and reform blueprints were forcing the hands of political parties, which were unlikely to bring about the much-desired national reforms.

"The country needs reforms in several areas, especially democratic development, distribution of wealth, and education. It isn't easy. We will tackle a strategic plan that controls our thoughts for 20 years," he said at a seminar on political parties and the path to reform hosted by the King Prajadhipok's Institute (KPI) to mark its 20th anniversary.

Democrat Party leader Abhisit Vejjajiva expressed concern that political parties would be restricted by the new laws and issues arising from it have to be addressed.

The laws on political parties are forcing [them] to be 'ready-made political parties', so it is an obstacle to their evolution," he said.

But why is the current junta and Thai Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha so keen in implementing a 20-year national strategy plan in the first place? According to the junta, it’s all about consistency.

Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office Kobsak Pootrakool, in marketing the controversial plan, said it is designed to solve the issue of inconsistency of government policies. “New governments often cancel the policies of previous governments and initiate new projects and each government has an average of two years in office,” he explained.

Kobsak’s words seem to be alluding to something the current government is working on: The Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC).

Eastern Economic Corridor

The Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) involves three eastern provinces off the coast of the Gulf of Thailand: Chonburi, Rayong, and Chachoengsao. It spans a total of 13,285 square kilometres and is expected to cost US$43 billion. The National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) believes the EEC will turn these provinces into a hub for technological manufacturing and services with strong connectivity to its ASEAN neighbours.

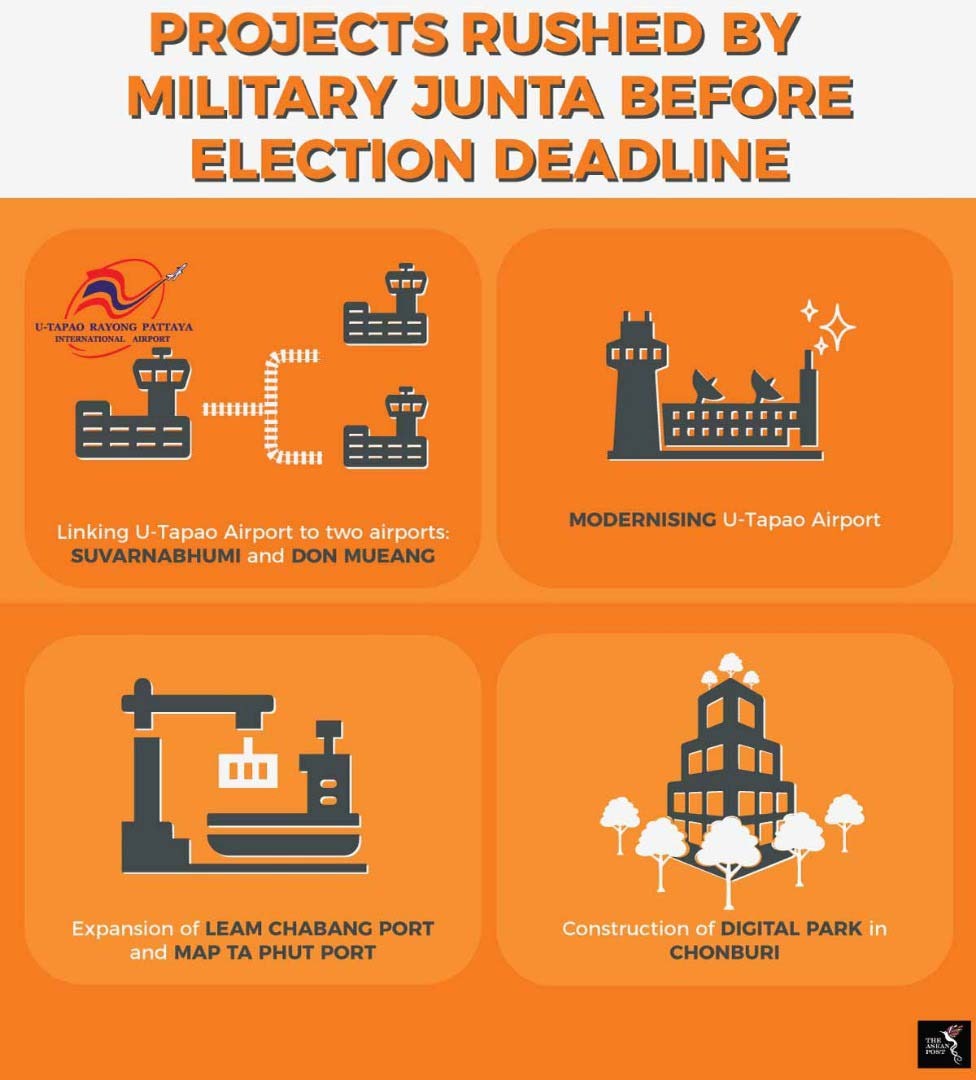

Previously, the junta was seen as rushing to develop the EEC before the coming election. It even opted to fast-track Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) to fund six of the most crucial infrastructure mega-projects worth US$20 billion with hopes that they will be well underway before the next election and instalment of a new government. The projects include a 220-kilometre high-speed airport rail linking U-Tapao Airport in the Rayong province to two airports in Bangkok: Suvarnabhumi and Don Mueang, the modernisation of U-Tapao Airport - a maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) facility at U-Tapao, the expansion of Laem Chabang Port and Map Ta Phut Port, and the construction of a “Digital Park” in Chonburi.

Thailand's groundwork with international investors found that potential bidders would only be interested if they were assured a majority equity stake in any joint venture with local firms to build and operate the line.

Now, with the 20-year plan restricting policy-making, it doesn’t seem like Thailand’s junta needs to rush anymore.

Related articles:

A revitalised Thailand by 2019?

Thai junta eyes Chinese investment