Vietnamese lawmakers have just passed a cybersecurity bill which would allow the government there to essentially censor the internet. The bill which was passed with an overwhelming majority by Vietnam’s rubber stamp parliament has come under fire from many quarters. The bill provides the government there with sweeping powers to control information on the internet.

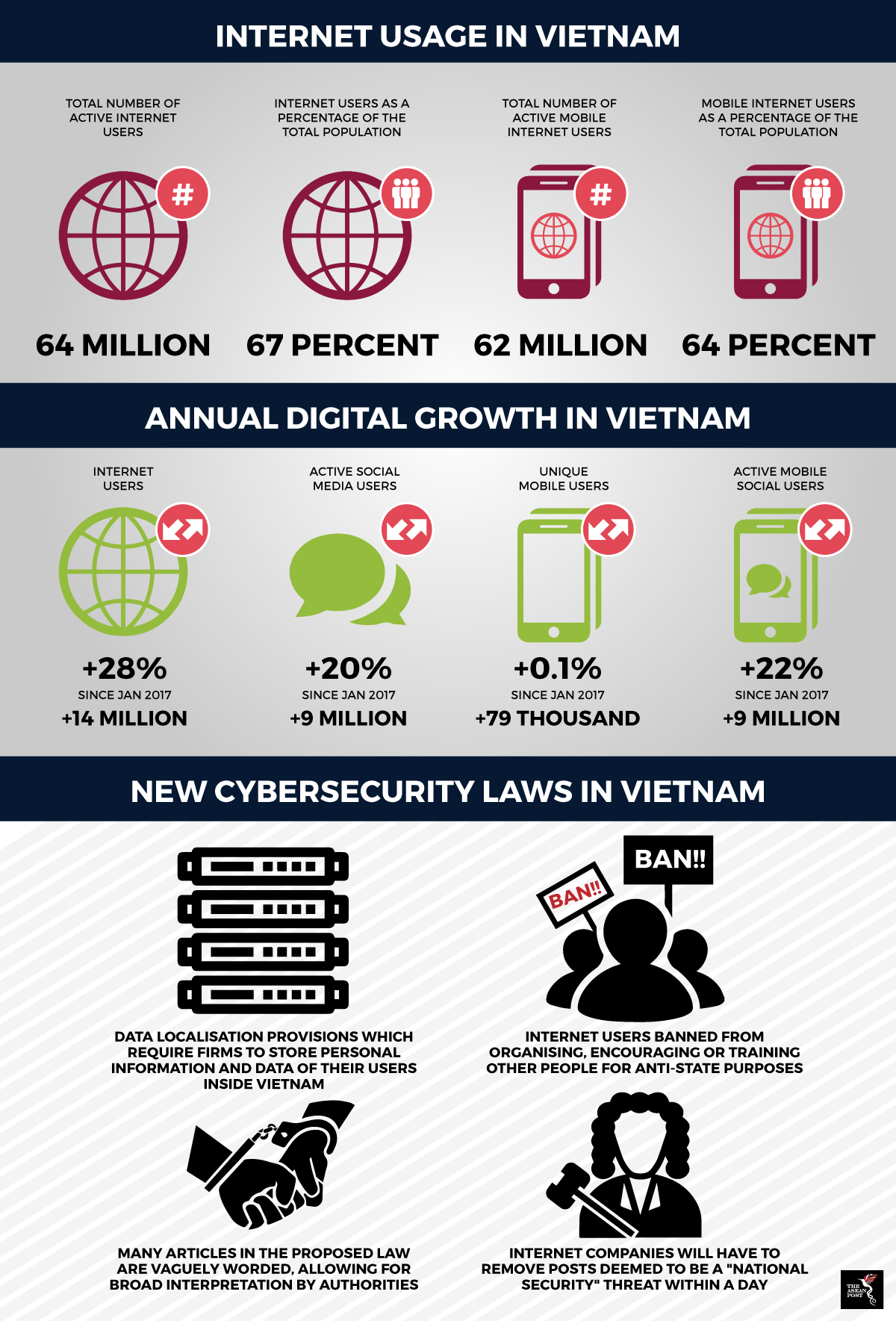

The new law, which comes into effect on 1 January 2019, disallows internet users from organising, encouraging or training others for anti-state purposes. People are also banned from distorting history and spreading false information which could create confusion or difficulties for the authorities when exercising their duties.

The ambiguous nature of the legislation’s wording which allows for broad interpretation by the authorities is also a worrying feature of the newly passed law. For example, several clauses could lead to people being charged for exercising their rights on seemingly broad and vague offenses like “negating the revolution achievement” or providing “misleading information causing confusion among the people”.

Reacting to the passage of this repressive law, Amnesty International’s Director of Global Operations, Clare Algar bemoaned that there is now no safe outlet for the Vietnamese people to express their ideas and opinions as the online space was previously the only place they could do so without fear of censure.

“With the sweeping powers it grants the government to monitor online activity, this vote means there is now no safe place left in Vietnam for people to speak freely,” she said in a statement released by the London based freedom watchdog.

Source: We Are Social

The country's leadership which has been in charge since 2016 is hyper-sensitive towards critical public opinion and has been waging a one-sided crackdown on dissidents. According to Human Rights Watch, an estimated 26 activists have been prosecuted in the first five months of the year.

At the end of last year, the government unveiled a 10,000-strong unit tasked to fight anti-state propaganda in the cyber realm. Dubbed Force 47, the brigade is already in operation to rebut government critics and to work to control web portals and blogs deemed to carry “wrong news.”

Inhibiting digital growth in Vietnam

The law also means that internet companies like Facebook and Google would have to remove posts that are deemed to breach provisions contained in the law within a day. Businesses are also required to store personal data within Vietnamese borders, thus dealing a blow to cross border data flows which are a vital feature of a growing digitalised global economy.

“Currently, Google and Facebook store personal data of Vietnamese users in Hong Kong and Singapore,” Vo Trong Viet, chairman of National Assembly's defence and security committee told lawmakers.

“Putting data centres in Vietnam will increase expenses for the service providers... but it is necessary to meet the requirements of the country's cybersecurity.”

Advocacy group for Facebook, Google, and other technology firms in the region, the Asia Internet Coalition, expressed their disappointment over this.

In a published statement, the group said that such data localisation requirements “will undoubtedly hinder the nation’s 4th Industrial Revolution ambitions to achieve GDP and job growth.”

“Unfortunately, these provisions, will result in severe limitations on Vietnam's digital economy, dampening the foreign investment climate and hurting opportunities for local businesses and SMEs to flourish inside and beyond Vietnam,” the statement read.

Data localisation remains a contentious issue as the world heads towards a more digital future. Supporters of such laws say that such enactments are vital to protect the privacy of Vietnam’s citizenry. Such arguments are also often rooted in the principle of national sovereignty as a breach of citizen’s data could constitute a threat to national security.

Others posit an economic and market driven argument. Barriers towards exchange of data could possibly harm economic welfare in a similar manner that tariff and non-tariff measures have on the free flow of goods and services.

Nevertheless, concerns surrounding data privacy are not to be understated. If anything, the Cambridge Analytica scandal and the recently revealed data sharing agreement that Facebook had with Chinese tech firms, only stand to validate fears that such amassed data could be put to use in nefarious ways.

However, the challenge for lawmakers is to construct legislation to curb misuse of data instead of stopping its free flow altogether. After all, such new challenges are a given as countries advance towards a more data-driven society.