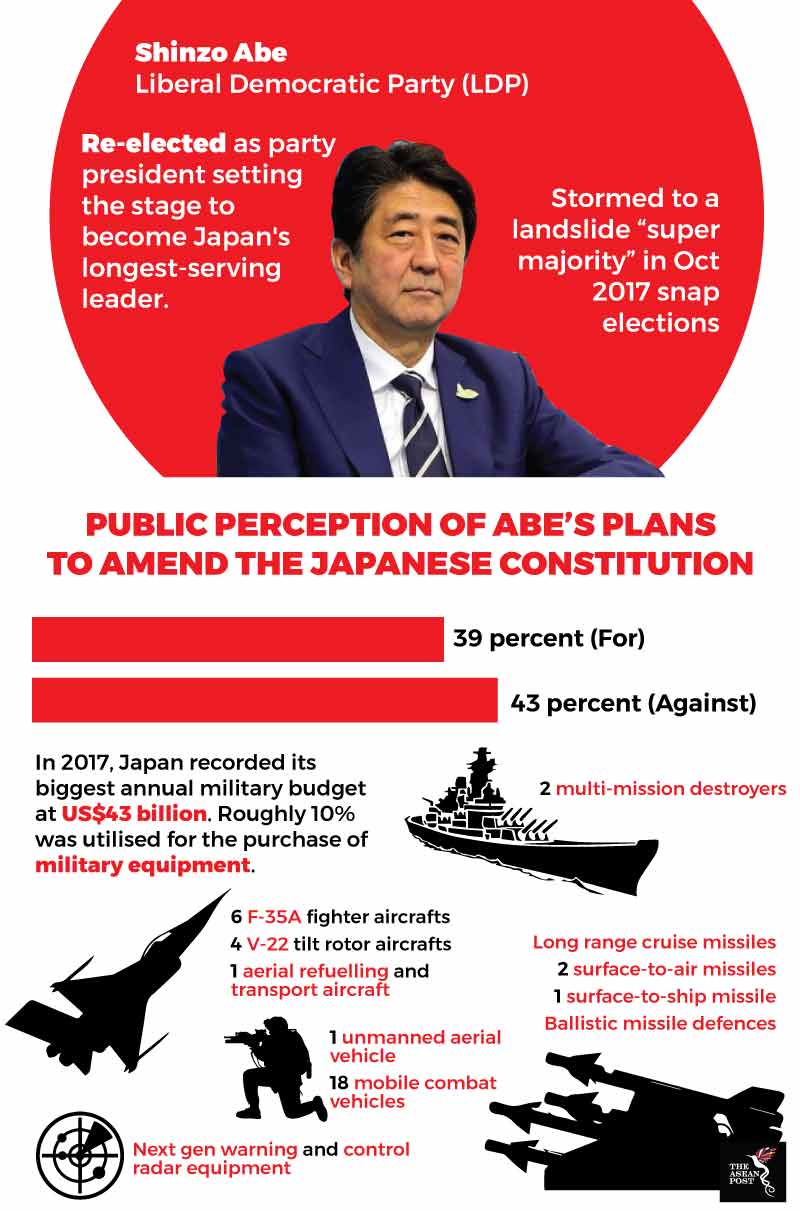

Last week, Japanese Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe emerged victorious in party polls, earning him a third consecutive term as leader of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). Abe took close to 69 percent of the vote, handing a thumping defeat to his sole challenger, former defence minister, Shigeru Ishiba.

With this victory, Abe is on course to becoming Japan’s longest serving Prime Minister. General elections won’t have to be called until 2021, hence he will likely surpass the 2,886 days spent by Taro Katsura – Japan’s Prime Minister in the early 1900s – in November next year.

Coupled with a strong majority in both houses of parliament, Abe is set to begin long desired changes to the Japanese constitution.

Revising Article 9

Abe’s fixation on Japan’s security policy stems mostly from his intention for his country to be more assertive in international affairs and not be held back by its belligerent past. Article 9 of the Japanese constitution which has largely shaped the country’s post war identity calls for the renunciation of “war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes.”

Nevertheless, Japan still maintains a pseudo-army - the Japanese Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) - which it argues is for “self-defence” against enemy threats. Although many critics of the JSDF claim that its existence if a violation of the country’s pacifist constitution.

Last year, Japan recorded its biggest annual military budget at US$43 billion. Although 44.2 percent of the budget was allocated for personnel maintenance like salary, retirement allowances and meals, roughly 10 percent was utilised for the purchase of military hardware and equipment. This included the procurement of several fighter aircraft, long range cruise missiles, radar equipment and the commissioning of two multi-mission 3,900-ton class destroyers.

With a fresh mandate from his party, the confidence of a majority of lawmakers and time on his side, Abe intends to move to add an additional paragraph to Article 9 which would officially recognise the JSDF. Symbolically, it would help legitimise the JSDF and raise its profile within Japan’s national bureaucracy.

According to Dr Bhubhindar Singh, Associate Professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, the functions of a legitimised JSDF would not differ much from the status quo of its current operations.

“I do not see a radical change in Japan’s military following the revision of the constitution. In fact, Abe will avoid this,” he said.

“The JSDF has increased its profile over the course of the post-Cold War period. It has expanded its capabilities, mandate, and influence over the security policymaking process,” he added.

Abe may also have to contend with domestic opposition to his plans. A recent poll by Tokyo-based Yomiuri Shimbun found that only 39 percent of respondents support this move – down from 45 percent previously. Meanwhile, 43 percent – up from 38 percent – are against the constitutional amendment.

Source: Various

Geopolitical domino effect

A “legitimised” JSDF would definitely raise the eyebrows of Japan’s immediate neighbours, especially China and the Koreas. Already, Japan is embroiled in a maritime dispute with China over the sovereignty of a group of uninhabited islands in the East China Sea which are believed to hold large oil reserves.

Singh, who is also an expert on international relations in Northeast Asia remarked that in light of maritime tensions with China, Japan strengthening its military would not be out of the norm, but he argued that this expansion of military capacity must be conducted within the United States (US)-Japan alliance.

“I think Japan is well aware that any military development on its part tends to raise suspicion amongst its neighbours. Hence, it works hard to strengthen the alliance with the US – not only to mitigate the negative reactions towards its own actions but for its national security,” he opined.

Yesterday, Abe met with US President, Donald Trump on the side-lines of the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in New York in what he described as a “very constructive” dinner meeting. While the meeting centred mainly on economic issues concerning Trump’s threat to impose tariffs on imported automobiles – a move that would severely impact the Japanese economy – other matters related to defence and security, including the progress of denuclearising the Korean Peninsula were also discussed.

The tremors of Abe’s actions would also be felt in Southeast Asia. For long, member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have relied on Japan to counteract Chinese hegemonic ambitions in the region.

“Japan is already assuming the role of a balancer against China’s widening influence and presence in Southeast Asia and East Asia. While ASEAN states have not openly said this, there is clear support for Japan to remain strongly engaged in Southeast Asia to counter China,” Singh explained.

Since the early 1990s, analysts and observers have pointed to ASEAN’s new role as “manager of relations” between competing spheres of influences to ease great power competition in the region. Most importantly, its role is endorsed by these greater powers due to ASEAN’s perceived centrality.

In responding to calls for a regional security dialogue, ASEAN rejected proposals that wouldn’t suit an Asian culture and instead, posited its own. The ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the East Asia Summit (EAS) were designed to function on the backbone of “The ASEAN Way”; a framework of cooperation reliant on the principles of non-intervention and consensus. It is only such an arrangement which can bring together major rivalrous powers like the US, China, Japan, Russia and even North Korea to the same table.

Singh further reiterated that an important component of Japan’s balancing strategy is to strengthen ties with Southeast Asian states via a range of areas namely East Asian multilateralism, maritime security and even defence diplomacy.

“Such a strategy will augment ASEAN’s role as a ‘manager’ within an ASEAN-led multilateral structure,” he concluded.

Related stories: