Malaysia celebrates the 60th anniversary of its independence from the British Empire on August 31, 2017. For sixty years, this proud Southeast Asian nation has adopted its own currency that is known today as the ringgit. Following the story and the origins of the ringgit, The ASEAN Post met with a Malaysian currency collector in the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur - the capital city of Malaysia. A collection of precious banknotes was on display in his shop including the very first "paper money" that was introduced to its citizens.

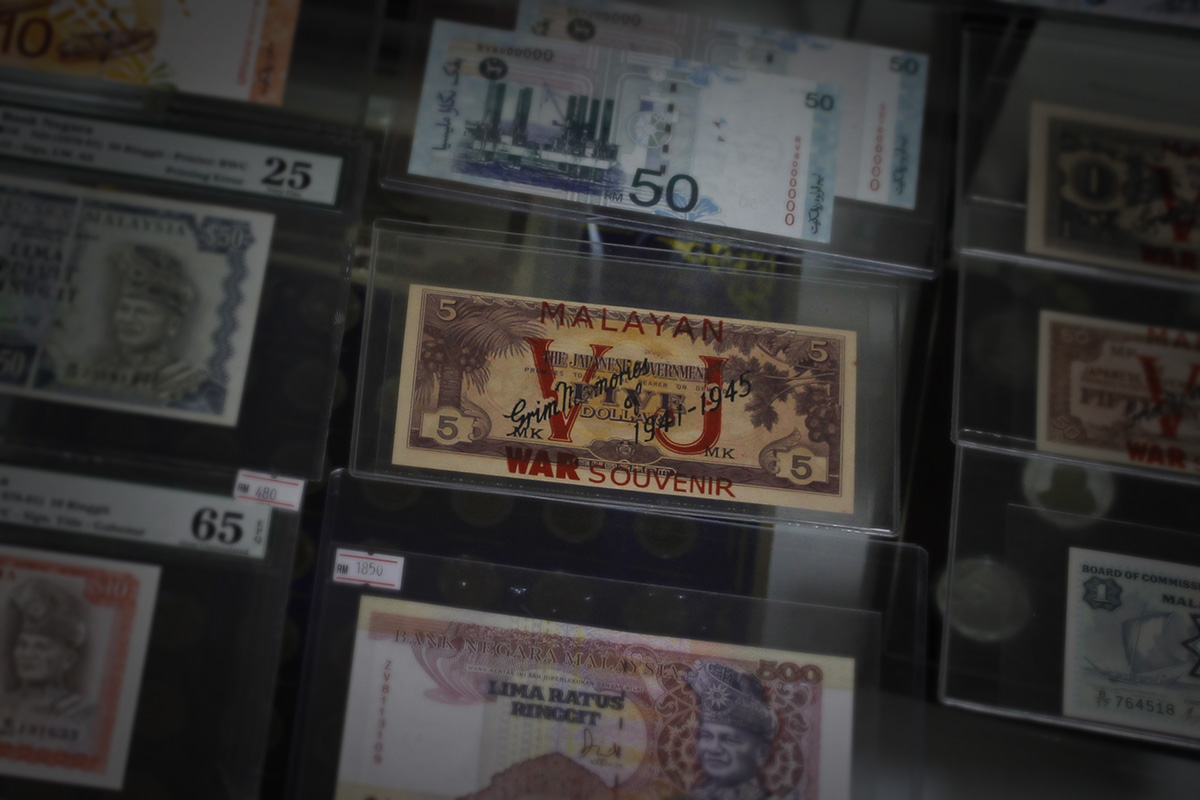

Currencies circulating in Malaya prior to the ringgit are highly sought after amongst traders and collectors for their rarity after going out of circulation. Many currency collectors travel overseas to verify the authenticity of these notes and their value. “Ringgit notes during the time of former Malaysian central bank governor Ismail Ali are often sought for and other notes with a higher value could even go into an auction,” he added. Other popular notes among collectors in the numismatic community include those from the era of the Japanese occupation of Malaya - more commonly referred to as the banana leaf note - which was in circulation between 1942 and 1945.

Brief history of the ringgit

The word ringgit is a Malay term derived from the word “jagged”. The official name for the Malaysian currency (ringgit and sen) was adopted in August 1975. Prior to this, it was known as the dollar and cent. In 1993, the currency symbol “RM” was introduced to replace the use of the dollar sign “$”. In 2004, BNM (Central Bank of Malaysia) had issued new "RM10" notes with additional security features including holographic strips that were only seen on the "RM50" and "RM100" notes previously. On July 16, 2012 BNM unveiled a new series of Malaysian banknotes and coins that was placed into circulation alongside existing banknotes, which have continued to be legal tender. Themed "distinctively Malaysia", the latest banknotes series draws inspiration from the country’s cultural diversity, rich heritage and biodiversity. The new banknotes series uses latest banknote technologies to enhance security features which include shadow image, clear window, watermark portrait with pixel and highlighted numerals, colour shifting security thread, micro lens thread, perfect see-through register and coloured glossy patch. The visually impaired are also able to benefit from specific features such as tactile identification to identify and distinguish the different denominations.

Malaysian currency display at the Bank Negara Malaysia Numismatics Gallery in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia on August 21, 2017. (The ASEAN Post/Khusrin Lani)

The Asian Financial Crisis

The Malaysian currency came under speculative attack after the baht (Thailand's currency) had also been attacked by unscrupulous speculators. In the case of Thailand, the baht was vulnerable to speculative attacks as much of its borrowings were from foreign sources and denominated in US dollars. So, when the baht dropped, speculation was rife that the borrowers’ cost of borrowing and servicing its facilities would increase and they may not be able to service their debt and repayment existing loans. This led to a pullback of foreign funds and short-selling of the baht resulting in further devaluation of the currency. And that triggered a frenzy of speculative attacks on to the baht.

Speculators then turned their attention to other currencies in the region including the ringgit. “And our currency was attacked till it hit the low of 4.54 to a US dollar. The speculators felt that the other regional currencies were similarly vulnerable as the Thai Baht. But, BNM was a prudent central bank. It did not allow much borrowing in foreign currencies, chiefly in US dollar. So, while we were attacked we were able to withstand it through capital controls and pegging the ringgit to the US dollar at 3.80. And we had reserves,” Dr John Anthony Xavier, Principal Fellow at Graduate School of Business, UKM (Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia) told The ASEAN Post. “So, we did not have to go to the IMF (International Monetary Fund) with a begging bowl in our hands as Indonesia was forced to do when its rupiah collapsed upon severe speculation.”

The impact of the financial crisis to the Malaysian economy

The attack on currencies across the region caused damage to economic fundamentals of many countries. In Malaysia, as was the case elsewhere, businesses failed as banks tightened lending and dished out less loans, thus making the availability of capital in the market limited. Lending was tightened because of increasing non-performing loans as businesses began to default shortly after the crisis. As businesses failed and workers lost their jobs coupled with decreasing government revenue, government expenditure had to be cut and it resulted in a contraction of the Malaysian economy.

Unpegging of the ringgit

Malaysia unpegged the ringgit on July 21, 2005 immediately after China abandoned its own currency peg, thus removing the near two-decade peg against the US dollar at 3.8. This allowed the currency to perform based on demand and supply without active intervention by BNM, limiting the role of the central bank in managing sharp spikes or falls in the ringgit’s exchange rate, or fluctuation in short.

“Also, there is no massive speculative attack as our currency is still non-convertible. Meaning, you cannot legally buy or sell currency overseas. So, they can’t buy overseas and dump ringgit to depress the exchange rate of the ringgit.” So, BNM’s policy is to let the ringgit float and let the economic and market fundamentals determine its true level. “If you peg it just because it is low, then it is going to distort trade – by making our exports more or less expensive depending on whether the ringgit is pegged higher or lower than its true value,” he added. Also pegging now will result in a confidence crisis on the economy and the ringgit and cause another massive outflow of funds.

Former Malaysian Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad can be credited with the masterful and contrarian move made during the Asian financial crisis - a move that raised eye brows and brought about many queries by traders and economists in the international markets when he had pegged the ringgit to the dollar. Such was its brilliance, the IMF had actually acknowledged the policy even though the IMF’s standard prescription was to cut budgets and remove subsidies, which was what happened in Thailand and Indonesia. “We had to peg the ringgit because it was being mercilessly assailed against by unscrupulous speculators. They lost money as a result of the peg and capital controls. But without the peg we would have been defenceless as our reserves were getting lower and would not have been able to support the ringgit,” Xavier said.

Having come a long way: ringgit's performance against other ASEAN currencies

At present the ringgit is performing well against other currencies in ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations). Prior to this, in the second quarter of 2017, the ringgit was also the strongest currency in ASEAN. This is because Malaysia’s economy has become more resilient, having recovered from the recent economic crisis. GDP (Gross domestic product) is forecasted to grow at 5.2 percent in 2017 and 2018. “With the gradual world recovery, we can expect greater demand for our exports, consequently, greater demand for our ringgit. US jobs growth is especially strong. So, with a strong economic growth in the US – another major market of ours – we can see the ringgit strengthening further.”

Further liberalisation of the currency market by BNM will see greater inflows of foreign funds and consequently the strengthening of the ringgit. Also, the BNM’s requirement to repatriate 75 percent of exporters’ receipts to the ringgit will continue to prop up the currency.

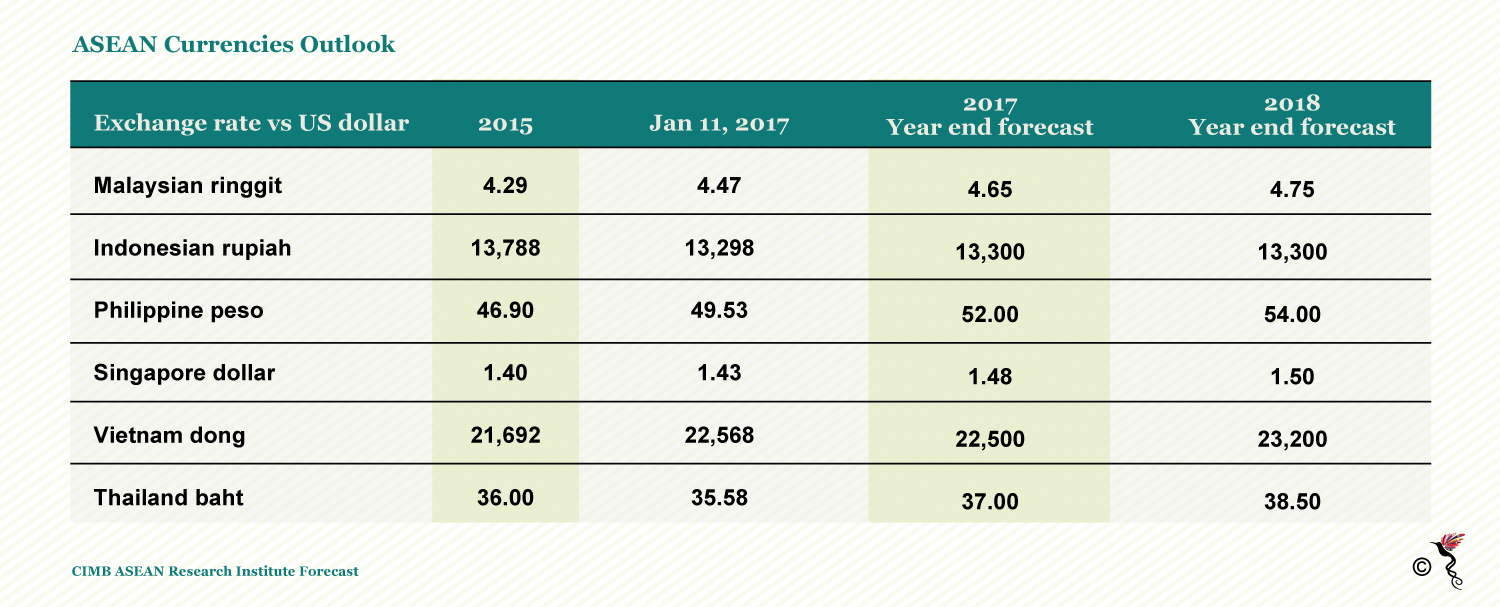

The outlook of ASEAN currencies in 2017 and 2018

As a 60-year-old country, the ringgit has endured many ups and downs while growing alongside the nation as part of its national identity. While CARI (CIMB ASEAN Research Institute) has forecasted that the ringgit will depreciate in value by the end of 2017 and 2018 based on current market sentiments and fundamentals, others remain optimistic the ringgit will strengthen against the US dollar for the rest of the year as the US executes a tighter monetary policy with further increases in its benchmark interest rate. Stable commodity prices for crude oil and palm oil - Malaysia's main exports - will also enable the ringgit to stabilise and strengthen in the coming months, reinforced by the recovery of the world economy.