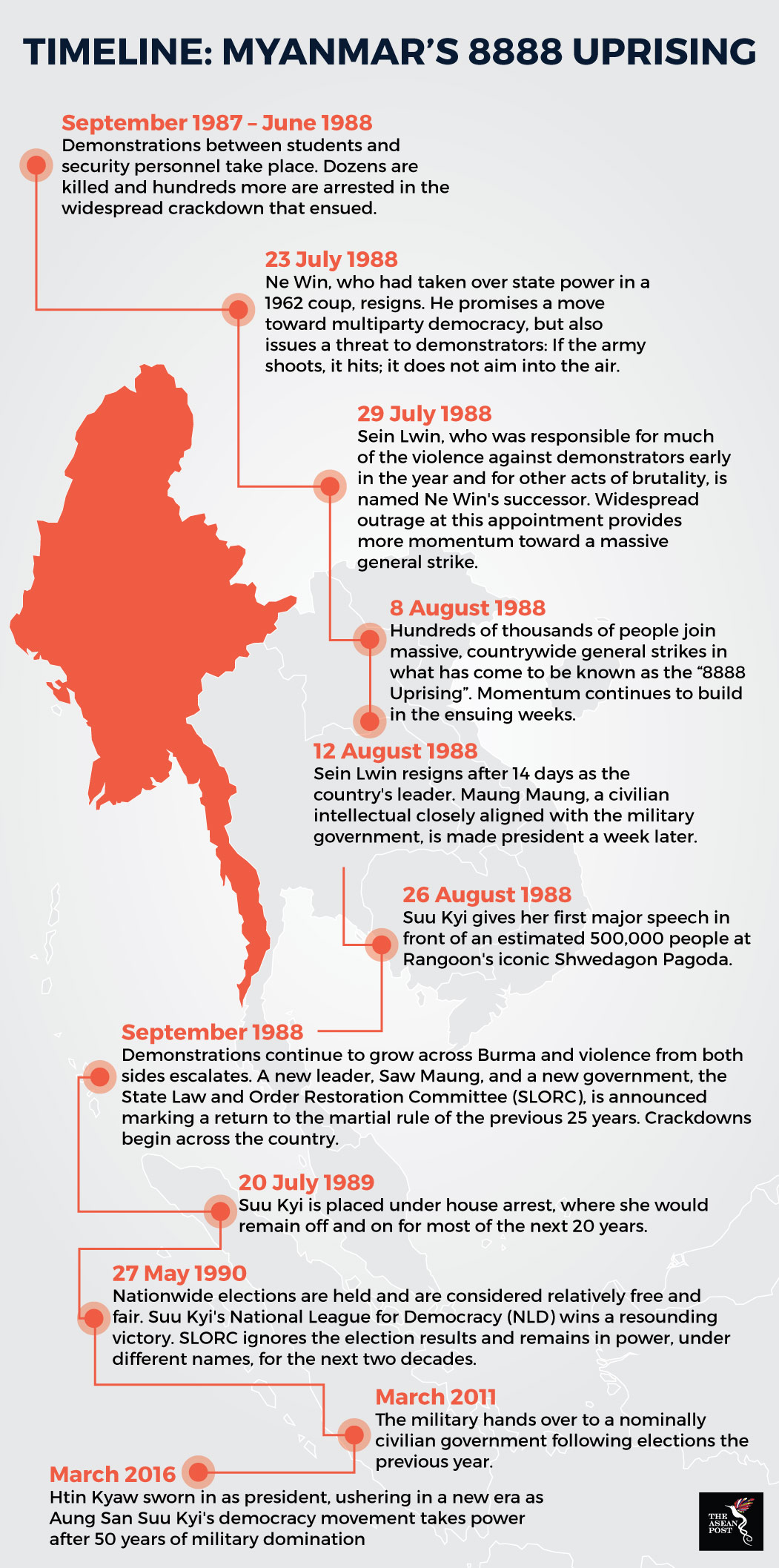

30 years ago, nationwide pro-democracy demonstrations in Myanmar saw hundreds of thousands of protesters take to the streets of then capital, Rangoon. Led mostly by student leaders, it was the largest mass protest in the country since its independence in 1948.

The 8888 Uprising, named after the date of the protest, 8 August 1988, remains a watershed moment in Myanmar’s history. Columns of demonstrators from all walks of life stood united under the emblem of the fighting peacock which would go on to become a powerful symbol of democracy in the country. Their goal - ousting a dictatorial regime under which, the country had been systematically oppressed since 1962.

Events, however, quickly took a turn for the worse. Troops known as the Tatmadaw began opening fire on protestors. In the weeks that followed, at least 3,000 demonstrators died as a result and thousands more were jailed. The military then took firm control of the government and initiated further crackdowns in September.

In the midst of the crackdowns, one icon would rise to become the face of the pro-democracy movement in Myanmar. Aung San Suu Kyi, daughter of Aung San who was a prominent figure in the nation’s fight for independence from the British would follow in her father’s footsteps and become the poster image for a renewed and democratic Myanmar.

On 26 August 1988, she stood outside the iconic Shwedagon Pagoda and addressed an estimated crowd of 500,000 people on the urgent need for the nation to transition to a democracy after an unsuccessful experiment with socialism.

However, the military would prove to have an upper hand in matters related to politics in the following years. Suu Kyi was placed under house arrest in 1989 and a year later, her party, the National League for Democracy (NLD) won a resounding victory in the national polls – sweeping 80 percent of the seats in parliament and 60 percent of the popular vote. However, the military led government there ignored the election results and remained in power for another two decades.

Source: Various sources

Lessons from the uprising

If there is one recurrent theme in Myanmar, it is that its military will always play a fundamental role in politics. The events of 1988 had initially sparked a fervour for democracy in the fledgling nation which has since been ebbed by the continuous heavy handedness of the military in state affairs.

Suu Kyi’s triumph in the 2015 general elections was heralded by the international community as the start of a fresh democracy in the Southeast Asian state. However, the veneer of the NLD’s civilian government hides the bitter truth that the military still wields significant power in the country.

In 2008, a new constitution was minted and as part of a political bargain to allow for the smooth transition from military to civilian rule, the Tatmadaw were allocated 25 percent of seats in Parliament. This unequivocally gave the military a veto to overrule any constitutional amendment which requires 75 percent support in parliament.

Besides that, the military also holds key ministerial portfolios and the constitution also contains vague clauses which allow for the military to resume charge in the event the country falls into disorder. In essence, Myanmar has remained a quasi-junta state.

The lack of frank and critical discussions of Burmese history and politics in the nation has also led to the events of 8 August 1988 to be consigned to vague memories and oral recitations of its survivors. History has always been a delicate subject in the nation and has been shielded from public debate for fear of corrupting the official, state-controlled narrative.

Most distinctly, renderings of history by the military government capitalising on ethnic fault lines have given rise to the humanitarian crisis in the northern Rakhine State. The Muslim minority living there are considered illegal “Bengali” immigrants from Bangladesh squatting on Burmese land and have been on the receiving end of a brutal crackdown campaign by the Tatmadaw.

Myanmar’s history is a sullen one, marred by instances of violence and military control. Moving forward, there is not much optimism that the junta there will relax its grip and make way for a proper democratic government. If the 8888 Uprising proves anything, it is that the people of Myanmar are not resistant to democracy. All that remains is for the army to relinquish its hold on power and allow the natural course of events to take place.