According to the Energy Transition Index (ETI) published by the World Economic Forum (WEF) recently, the world’s 114 countries are not making the transition to sustainable energy systems fast enough to tackle the issue of climate change.

In general, the term ‘energy transition’ refers to the shift from current energy production and consumption systems, which rely primarily on non-renewable energy sources, to a more sustainable, lower-carbon energy mix.

The ETI benchmarks countries based on the performance of existing energy systems, as well as their readiness to transition to a secure, sustainable, affordable, and reliable energy future.

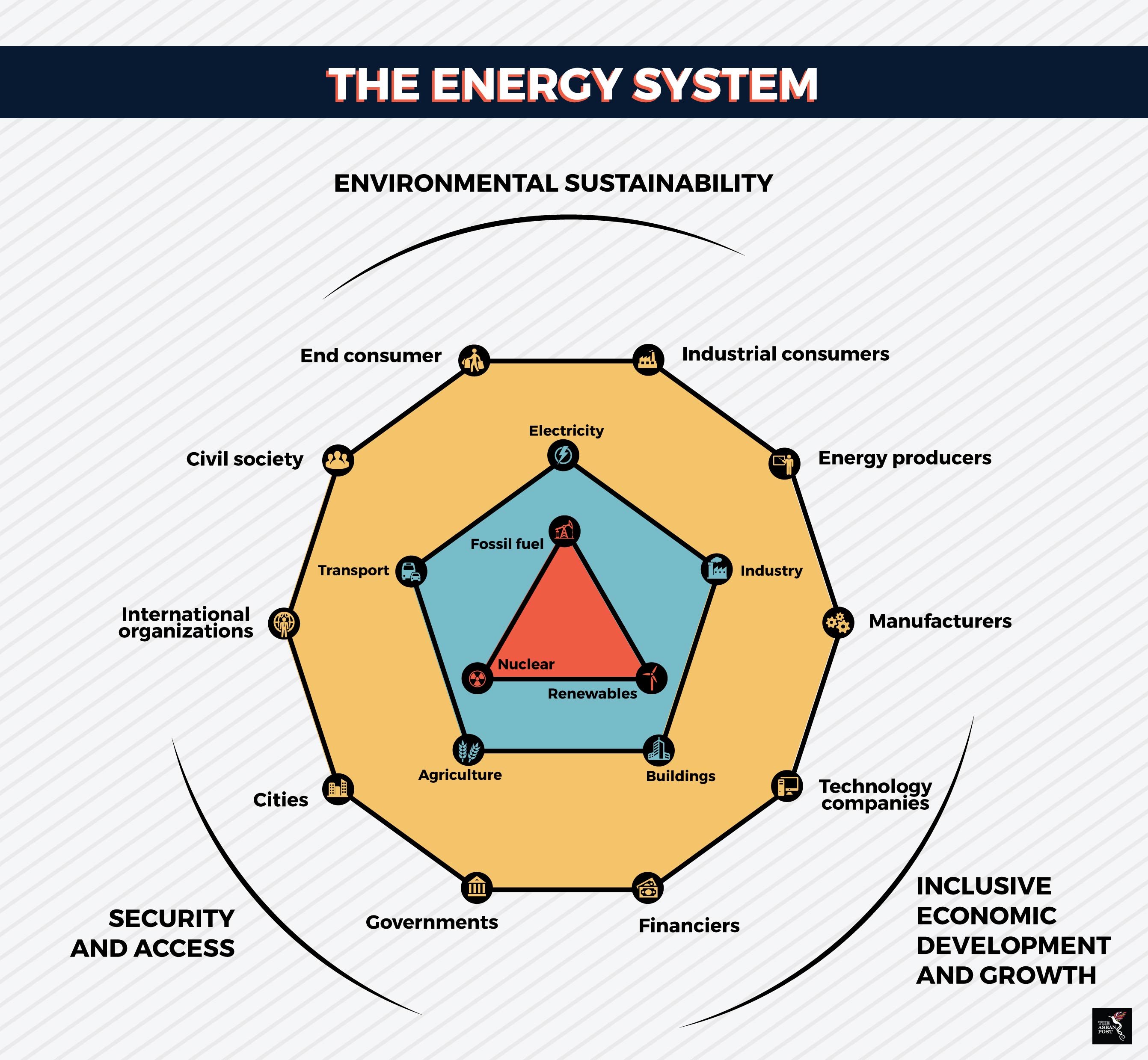

An energy system comprises a country’s entire energy picture, including all its stakeholders, various energy sources and multiple energy-consuming sectors.

‘Transition readiness’, meanwhile, refers to the degree to which a company’s energy system has the political, economic and social structures in place to allow a transition to a more secure, reliable, inclusive and sustainable energy system that fosters greater economic development

Out of the 114 countries surveyed, 93 were reported to have experienced overall improved ETI performance. Singapore, in 12th spot, ranked highest in Southeast Asia, while Malaysia ranked 15th.

In general, energy systems are meant to support society in the three energy dimensions, namely secure and reliable access to energy, environmental sustainability and inclusive economic development. These three dimensions comprise the energy triangle that measures the effectiveness of any energy transition strategy in the long-term.

Source: World Economic Forum, McKinsey & Company

How ready any one country is for the energy transition, on the other hand, depends on the standard of existing energy infrastructure in a country, the credibility and stability of long-term political commitments, and the availability of capital to finance the energy transition.

All these factors are still in early growth stages in Southeast Asia, which is expected to remain heavily reliant on fossil fuels in the short term to meet growing energy demands.

Energy consumption in the region is expected to increase 4% annually, hitting 595 Mtoe in 2025. This increase is anticipated to be driven mostly by the electricity and demand sectors. The demand for energy to produce electricity is expected to increase 95% by 2025, and for industry by 63%.

Southeast Asia’s energy transition is driven by longer-term goals like the need to provide greater energy security and access, as well as to address issues of human health and environmental degradation.

Energy production related emissions in Southeast Asia could rise by 61% to 2.2 gigatonnes in 2025, according to estimates by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Yet high carbon emissions are also the product of industries such as forestry and agriculture in countries like Indonesia, where these sectors provide high contributions to economic growth.

In making the energy transition, Southeast Asian countries have so far implemented policies that both, encourage the development of renewable energy and simultaneously increase energy efficiency.

In order to reach a 17% renewables share in the energy mix by 2025, the region needs to accelerate its efforts to create an enabling environment, including setting the right policy and putting the financing landscapes in place.

Any policies made have to balance the need for certainty against room to integrate new technologies and business models when needed. On the other hand, adequate financing structures, such as financing schemes, partnerships and funds would also need to be provided by governments to foster these initiatives.

In terms of energy efficiency, Southeast Asia is on the right track. Its energy intensity, which measures energy efficiency, has been on a steady decline between 2005 and 2014.

Each ASEAN nation has also allocated the necessary financing to back efforts to reduce energy consumption and intensity. The use of public-private partnerships is still growing in the region, while partnerships with energy service companies are also being tested to create more low-cost and more flexible energy solutions for governments to work with. Barriers may persist concerning fixed electricity pricing structures, due to the imposition of government subsidies on fossil fuels but these are also deeply entrenched issues which require political will to upheave.

Southeast Asia’s energy transition is still unfolding. Targets to keep it on track are also being supplemented with the necessary policies. What still remains to be done is to input the necessary regulatory frameworks that will help attract higher foreign investment. Southeast Asia, after all, has the same energy goals as everyone else, and will likewise have to do what it takes to meet them.