Airbnb took the world by storm by serving as a marketplace connecting travellers to people offering short-term accommodation in their homes. Nearly a decade after its formation, blowback against home-sharing is threatening to take the wind out of its sails.

Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia decided to rent out three air mattresses in their San Francisco apartment living room. There was a severe shortage of hotel rooms in town due to a convention. Together with a former roommate, Nathan Blecharczyk, they formed Airbnb in 2008.

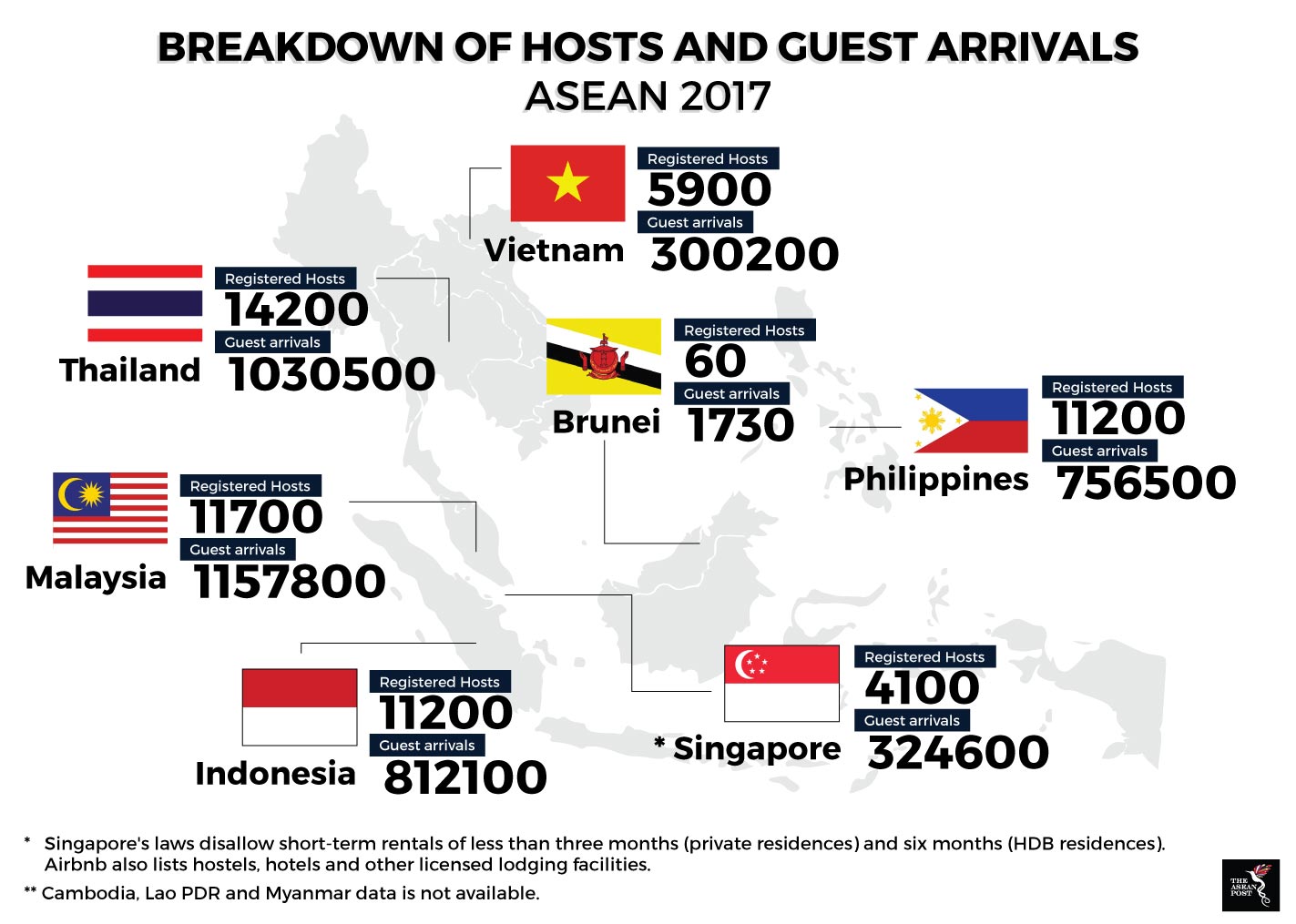

By March 2009, Airbnb had 10,000 users and 2,500 listings. Today, it boasts nearly five million listings in 81,000 cities in over 191 countries. Thailand hosted 1.2 million Airbnb guests in 2017, while Malaysia welcomed 1.5 million guests, despite Sabah – one of the country’s states – declaring Airbnb-type businesses as illegal.

Singapore also declared Airbnb illegal for the same reason as Sabah: residential properties may not be used for commercial or industrial activities. It outlawed rental of private residential properties for less than three months, and Housing Development Board (HDB) properties for less than six months. In April, two Singapore Airbnb hosts were fined US$44,085 each for flouting the law.

Restrictions and conditions

Most recently, Japan enacted new minpaku laws on short-term home-shares to increase lodging options for visitors travelling to the 2019 Rugby World Cup and 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

However, the law limits rentals to 180 days per year, making it harder to earn a profit. Home owners must register their properties with the local government, undergo fire safety checks and also prove that they are mentally sound.

Local governments added other restrictions and conditions. Tokyo’s Chuo ward bans weekday rentals to avoid having strangers around apartments while others are away at work. Some councils allow minpaku only during school holidays to avoid children bumping into strangers on the way to and from school. Kyoto permits minpaku only from 15 January to 16 March, outside the local peak tourist season.

Airbnb also faces resistance in cities such as Palma, London, Barcelona, Berlin, Amsterdam and New York revolving around zoning, vandalism, social, safety, taxation and regulatory issues.

Source: Airbnb

Short-term rental units are lucrative, prompting landlords to turn their units into home-shares or raise rent on their long-term tenants. This causes a shortage of affordable housing for locals, who either have to bear with higher rents or relocate to cheaper locations. This in turn, changes the character of the neighbourhood.

Residents are also concerned about their safety given the ever-rotating presence of strangers in their midst. Visitors may also turn rowdy, noisy and disruptive during their stay.

Home-shares directly compete with budget and small boutique hotels, which are licensed and comply with local laws and safety regulations. Home-shares are not held to the same standards.

The home-share industry is a double-edged sword. While it brings in tourists and much-desired revenue, it is also disruptive to local residents and authorities, prompting knee-jerk reactions. Japan’s stifling rules put a limit on the profitability of home-shares, to keep long-term rents low; and minimise the exposure of locals to strangers.

Well-intended or not, the minpaku laws have had unintended consequences: Airbnb was forced to remove almost 80 percent of its Japan listings in June.

Lucrative market

ASEAN countries are among Airbnb’s fastest growing markets in the world, said Mich Goh, Airbnb head of policy for Southeast Asia. “Tourists increasingly want new, adventurous and local experiences when they travel. For them, Airbnb is the antidote to modern mass tourism and a gateway to experience true ASEAN hospitality.”

She noted that 44 percent of all Airbnb guest spending takes place in neighbourhoods where they stay. In the Greater Mekong region, for example, Airbnb brought in five million visitors and generated US$1.67 billion in revenue for local economies last year.

“A typical host in Thailand earned US$2,100 renting out their space 29 nights a year. In Malaysia, a typical host earned US$1,200 renting out for 18 nights a year,” she added.

Airbnb compiled a Policy Tool Chest that documents how the company works with various jurisdictions and their policies. In some jurisdictions, it collects taxes for the government. In San Francisco and New York, Airbnb restricts hosts to only one address each. In London, hosts are automatically limited to 90 days of sharing; Amsterdam, 60 days; and Paris, 120 nights.

Future

The Policy Tool Chest provides real-world examples for local and national governments to consider. As home-shares grow and bring in valuable revenue, ASEAN countries need to formulate a consistent and sensible set of regulations that balances the needs of hosts and the communities they live in.

They could create a new category in the hospitality industry, with less stringent requirements on number of rooms, sizes and services offered. All hosts must then be licensed and comply with health and safety regulations.

Such hotels may be restricted to certain districts, thereby limiting the inflation of rentals only to those districts. For apartment buildings, home-shares may be confined to certain floors to minimise disturbances to residents.

With sensible management and regulation, governments will benefit from the influx of tourists and their spending, and hosts may earn an income without disrupting the lives of local populations. Then, the winds of change will be positive and not a blowback.