Part 1: The need for e-commerce taxes in local economies

The introduction of e-commerce taxes in Singapore is very likely, a Bloomberg survey conducted between 12 economists in February 2018 concluded. Singapore’s next budget tabling, scheduled to take place on 19 February, is anticipated to provide for the taxation of online vendors operating within that region.

E-commerce is defined by the Financial Times Lexicon as the buying and selling of goods over the internet, and may refer to business-to-business (b2b), business-to-customer (b2c) or consumer-to-consumer (c2c) transactions.

"Currently companies are subject to different e-commerce tax regimes, in some cases, none, across ASEAN," Steven Sieker, head of Baker McKenzie's Asia Pacific tax practice group told the Financial Times in January 2018.

Projected growth of e-commerce in Southeast Asia is expected to grow from US$7.7 billion in 2017 to US$64.8 billion by 2021, according to analysis by BMI Research in 2017.

In Singapore, e-commerce spending is expected to increase to US$3.8 billion this year, rising 12.4% from 2017, according to data from Statista. Foreign e-commerce players like Tencent, Alibaba and Amazon are taking advantage of Singapore’s low-risk business environment to enter other markets in Southeast Asia, according to the Singapore Business Review.

E-commerce taxes are aimed at levelling the playing field between e-commerce players. Under existing taxation laws, only local players fall within local tax regimes, and not foreign companies.

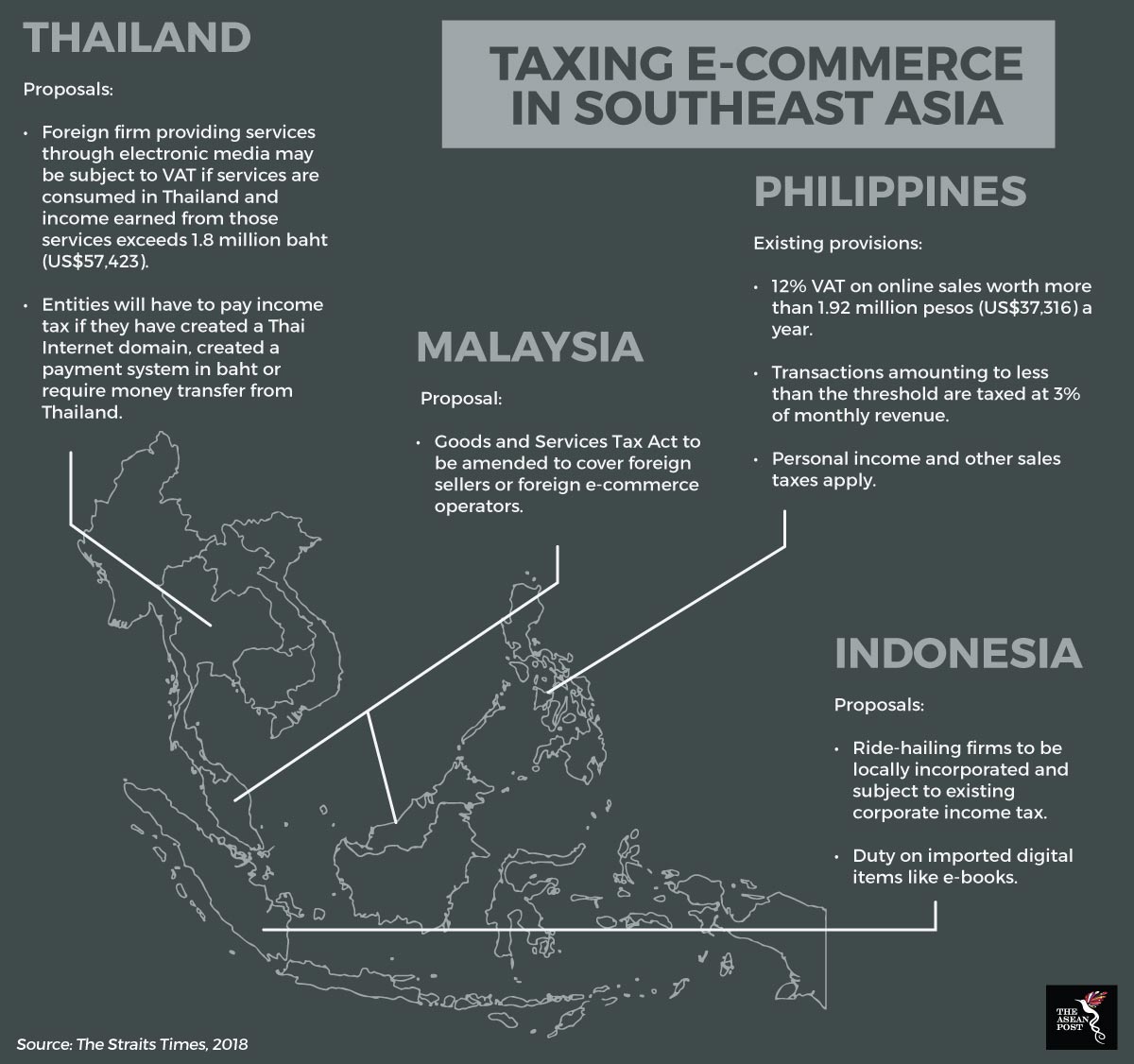

This was a point raised by Pawoot Pongvitayapanu, president of the Thai E-commerce Association which pushed a draft e-commerce tax law there. As of July 2017, Thailand, through its Inland Revenue Tax Department’s draft e-commerce tax law, includes a 15% taxable income rate for foreign online businesses who receive advertising fees, hosting fees or any other types of income prescribed under the Ministerial Regulation, according to Lexology.

Pongvitayapanu said that embracing foreign e-commerce players only offered short-term benefits for the local economy.

“In the long run, it will create dominant players, similar to the US retail market dominated by Amazon.com. Chinese players will dominate every aspect of logistics, payment and retail,” she told TechWire Asia in November 2017.

One option for Singapore is to remove the S$400 threshold beyond which GST becomes chargeable for online transactions.

“There is a significant portion of consumers not paying GST, as they don’t need to pay that if they buy less than S$400 from an overseas site,” Kurt Wee, Singapore’s Small & Medium Enterprises (ASME) president told Today Online recently.

Comparisons can also be made with e-commerce tax regulation models in other Southeast Asian countries.

Indonesia’s e-commerce revenue makes up just 0.75% of its GDP to date, according to the Institute for Development of Economics & Finance (Indef). Yet Indonesia is likely to introduce e-commerce taxes as a way to boost government revenues for infrastructure spending, according to reporting by Nikkei Asian Review in November 2017. This was confirmed by Sri Mulyani, Indonesia’s Finance Minister on 19 January 2018, after conducting a number of consultations with local agencies and ministries, as reported by Bloomberg.

She stressed that the Indonesian government is likely to protect small and medium enterprises, which form a large part of the newly-taxed vendors, by imposing lower taxes on them. The backlash by such businesses has delayed initial plans by the Center for Indonesia Taxation Analysis to finalise e-commerce tax regulations by October 2017, according to reporting by the Nikkei Asia Review. Bridging the gap between offline and online tax revenue models would mean imposing a 10% value-added tax (VAT) on online vendors, boosting government revenues by 20 trillion rupiah annually but also hampering the growth of small-scale vendors.

“They want to help, but then they also want to have their share. So, what is their position?” queries Hermawati Setyorinny, chairman of the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises and Industries Association of Indonesia.

Meanwhile, it was announced by Malaysia’s government in 2017 that it was mulling the extension of its 6% Goods & Services Tax (GST) to foreign e-commerce providers.

“We are amending a few of the tax laws, especially with regards to the GST, to collect taxes from foreign companies that offer digital services in Malaysia,” Subromaniam Tholsy, director-general of Malaysia’s customs department told The Financial Times in January 2018.

The Philippines is the only Southeast Asian country which has already implemented e-commerce taxation. Currently, a 12% VAT is placed on total value of online transactions of more than US$37,310 since 2016. For transactions less than that, a 3% VAT on online transactions is levied instead. Still, the Philippines faces difficulties enforcing these taxes on different online business models; clamping down on websites only leads to them forming a similar one under a different IP address.

As is clear, each government is beset by its own challenges in introducing e-commerce taxation and these will have to be met on a localised level, given the various localised issues. Southeast Asian governments would need to give the actual implementation of e-commerce taxes a lot of thought before these taxes can serve as a useful tool in advancing individual economies.

In Part 2, we will explore further the wider challenges of imposing e-commerce taxes on an international scale.