The ongoing trade war between the United States (US) and China is set to dominate discussions at the World Economic Forum on ASEAN currently being held in Hanoi. Some of Asia’s top business heavyweights and leaders are expected to attend the forum from 11 to 13 September.

Over the past few months, US President Donald Trump has not lifted his foot off the gas as he persists with a slew of tariffs on China, the country which the US imports the most goods from. Trump’s aversion with the US’ more than US$220 billion trade deficit with China risks not only trade relations with Beijing but market sentiments elsewhere, especially in the Southeast Asian region.

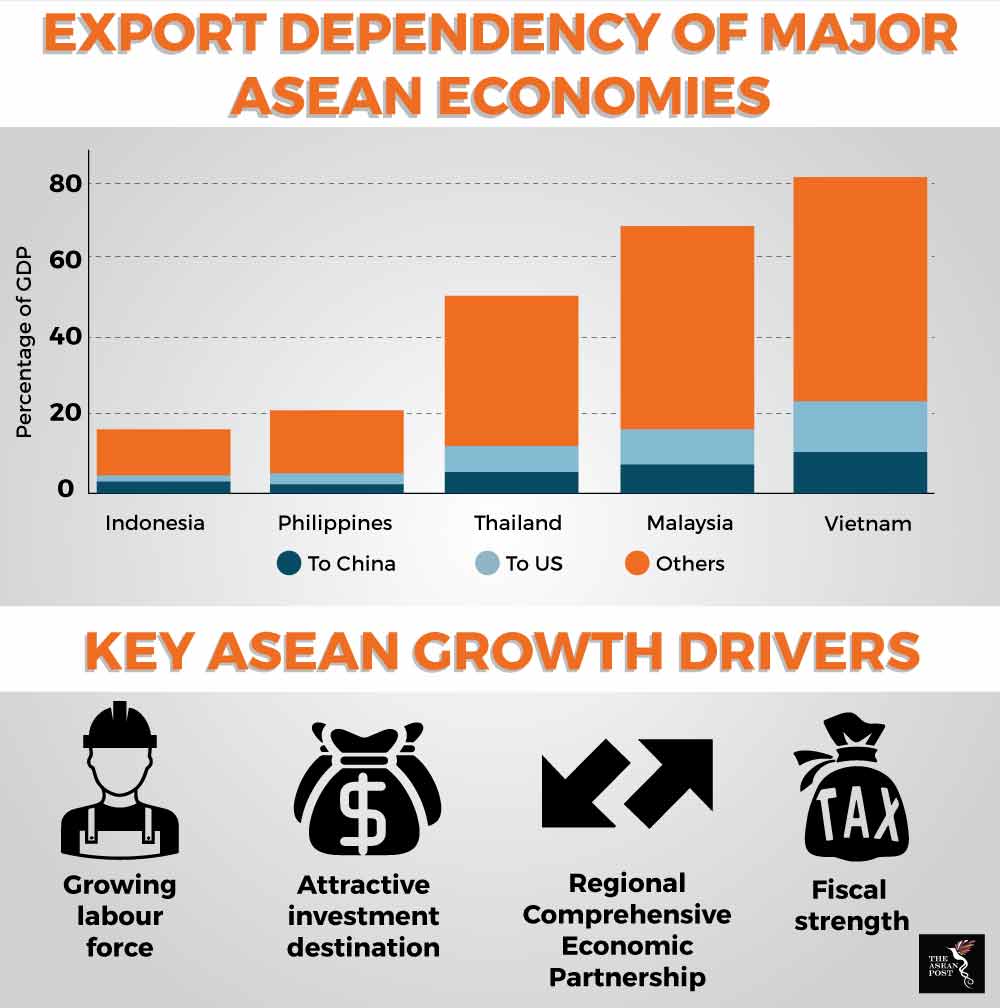

With Trump showing no signs of standing down, governments in the region which have embraced the values of trade liberalisation are now on the back foot – especially since most ASEAN economies are export-oriented. At around US$27 billion, Vietnam’s annual exports to the US ranks the first amongst its ASEAN peers making it relatively more exposed to the effects of tariffs and softening US consumer demand.

Countries like Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore could also suffer from the ripple effects of this trade tiff as they function as intermediaries within the global supply chain. Asia is home to a sprawling production network in which many Southeast Asian economies are at its heart – providing intermediate and raw goods to China which is then assembled and exported to predominantly western markets. According to a 2017 report by the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, intermediate goods account for upwards of 50 percent of Southeast Asian exports and imports with China.

In an effort to sidestep the effects of tariffs on production costs, many Chinese firms are looking to shift their manufacturing bases to Southeast Asia. This could be perceived as a net gain for economies in the region, coupled with lower labour wages here compared to mainland China.

However, in the longer term, the tariffs could dampen this rosy outlook if the Trump administration actively works to remove any loopholes that Chinese firms might exploit. Trump’s barrage of tariffs on Chinese solar panels earlier this year sought to plug gaps in the tariff regime of the previous US administration which allowed Chinese companies to skirt duties by moving production to neighbouring countries.

Source: Various sources

Regional cooperation

Amid global protectionist undertones, it is integral for economies in the region to improve domestic demand so as to fuel growth and reduce dependence on exports that have been slapped with tariffs. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates that strong investment and domestic consumption will accelerate growth in the region specifically in markets like the Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand while further industrialisation will boost Vietnam’s.

ASEAN’s emerging middle-class segment is slated to represent two-thirds of the overall population by 2030, more than double compared to 29 percent in 2010. This segment would be more willing to pay for products of higher quality, convenience and choice, thus driving demand for more goods in the market.

Moreover, ASEAN member states and several other Asia-Pacific economies are at the precipice of signing the largest free trade deal in the world. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) encompasses 25 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP), 45 percent of the world’s total population, 30 percent of global income and 30 percent of global trade.

In a recent round of negotiations held in July, two additional chapters namely the chapters on Customs Procedures and Trade Facilitation and Government Procurement were concluded, bringing the total concluded chapters to date to four. Leaders are now set to sign off on a broad agreement of the trade deal at the Singapore ASEAN Summit in November.

The signing of the RCEP goes against the current global flavour of a pushback against globalisation and economic cooperation. Ultimately, such a robust trade regime could lead to the grander aspiration of a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP).

The next chapter in the story of ASEAN’s growth would see deeper economic linkages developed between member states and regional partners. In doing so, ASEAN can serve as a riveting model of regional economic cooperation.

Related articles:

WEF on ASEAN: Asking the difficult questions