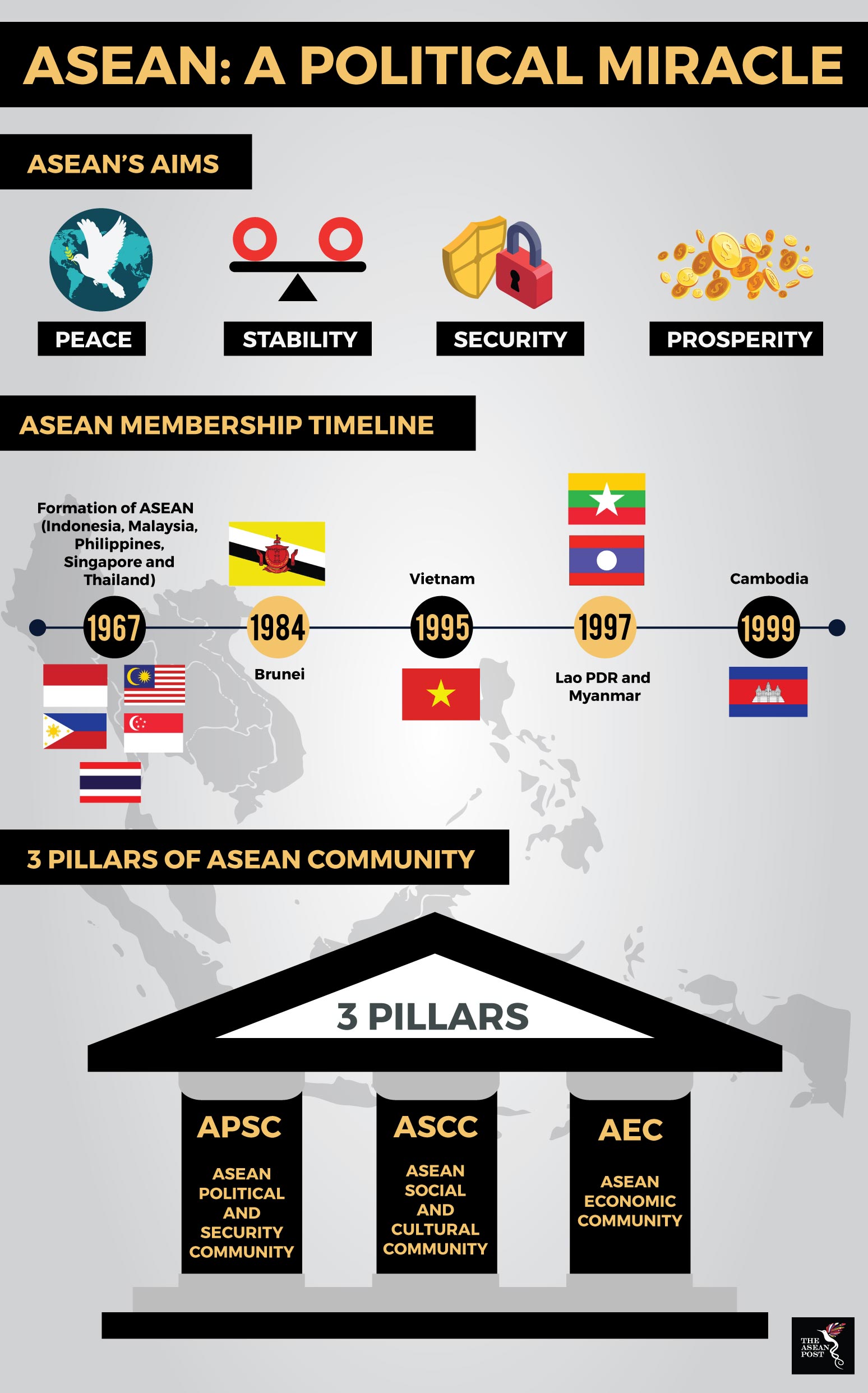

Today, diplomacy is still the preferred tool of international relations. Global multilateralism has seen the rise of regional intergovernmental organisations like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) which has served as a vital diplomatic instrument in enhancing regional cooperation and fostering unity within the Asia Pacific.

ASEAN has always been a mixed bag of sorts to diplomats and observers alike. Formed in the 1960s as a bulwark against the Soviet red scare, many had previously consigned ASEAN to an insignificant future after the fall of the Berlin Wall. However, ASEAN defied expectations and is still very much relevant today.

To understand how ASEAN accomplished this, it is useful to draw some parallels to jazz music.

“Diplomacy is like jazz: a constant improvisation on a theme.”

This apophthegm, credited to the late Richard Holbrooke – an exceptionally bright and formidable United States (US) diplomat who most famously brokered an end to the Bosnia-Herzegovina conflict – rings true amidst the shifting geopolitical tectonics of this region. What Holbrooke observed was that diplomacy wasn’t necessarily linear in fashion – in short, one knows the destination but can’t quite get there directly.

Harvard academic and expert on negotiation, Michael Wheeler in his 2013 book, The Art of Negotiation, makes a similar correlation. He argued that by mimicking what jazz masters do, we can become better negotiators ourselves.

Source: Various sources

Where classical forms of music are highly reliant on the conformity towards orchestral sonorities, jazz music flourishes on instrumental diversity. The harmony between the euphony of the soloist and the “comping” of the supporting musicians alludes to the defining characteristic of jazz music – improvisation.

“The answer in both jazz and negotiation is venturing out into unfamiliar waters far enough to be energized and creative, but not so far that you are in over your head,” he writes.

In many ways, ASEAN has been a maestro of “diplomatic jazz” in that it has improvised in its role and successfully waded into uncharted diplomatic territory. The reason why ASEAN survived well past its “best before” date is because it has evolved from its previous role, which was dependent on Cold War logic. Modern geopolitical realities are underpinned by stiff US-China competition in the region and within this context, ASEAN has secured a role as “manager of relations” between the competing spheres of Chinese and American influences in the region.

Most importantly, its role is endorsed by these greater powers due to ASEAN’s perceived centrality. In responding to calls for a regional security dialogue, ASEAN rejected proposals that wouldn’t suit an Asian culture and instead, posited its own. The ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the East Asia Summit (EAS) were designed to function on the backbone of “The ASEAN Way” – a framework of cooperation reliant on the principles of non-intervention and consensus. It is only such an arrangement which can bring together major rivalrous powers like the US, China, Japan, Russia and even North Korea to the same table.

In his book, Wheeler echoed Professor of Music in the Jazz Department at the University of Michigan, Ed Sarath’s 80-20 rule – that jazz musicians and likewise negotiators, should be 80 percent within their comfort zone and 20 percent outside of it. In this sense, ASEAN is very much comfortable working within the comfort of “the ASEAN Way” which others may perceive as stifling due to its slow process. However, because of ASEAN’s diverse constituents, that is the only way for such an organisation to remain intact. It cannot afford radical change which may disrupt its normative decision-making nature and risk undoing all that has been achieved thus far.

As a jazz ensemble, sometimes ASEAN makes it up as it goes along and this could have dire consequences on its strength as a regional association. ASEAN leaders must be mindful that between great powers which seek to ensnare ASEAN to their own orbits of influence – thus splitting the organisation – ASEAN need not choose. Instead, it can pick both sides and be creative in its diplomatic conduct as it endeavours to maintain regional peace and prosperity for years to come.