Liberalising the ASEAN-EU market for trade was a key objective of the sixth ASEAN-EU Business Summit held in Singapore on 3rd March. Foundational to this, however is ASEAN integration, which contemplates the free movement of goods, services, investments and skilled labour in order to unify businesses and consumers in the Southeast Asian region.

Key building blocks for realising the full potential of ASEAN economic integration include improved connectivity and the implementation of an efficient, secure and integrated transport network. One of the ways to facilitate greater trade is to improve customs procedures. The recent adoption of the ASEAN Single Window by five ASEAN member states was a milestone because it implements a single platform for the exchange of electronic certificates between ASEAN countries. Once it is fully ratified, electronic certificates will be used to assign preferential tariff rates which will further expedite goods exchange.

How precisely does ASEAN integration foster trade liberalisation? Panellists in the first plenary session at the summit pointed out that the possibility of a region-to-region free trade agreement between the EU (European Union) and ASEAN was in the works, but regional trade liberalisation could only be fostered once the necessary frameworks and systems were in place in each country.

Even if it imposes lower regional tariffs to the outside world, existing disparities in the minimum wages of workers across Southeast Asia would still afford them unequal access to incoming imports of goods and services. In some cases, according to U Moe Kyaw, Managing Director of Myanmar Marketing Research & Development Co, an entire day’s wages received by any one worker was equivalent to the price of a Starbucks drink in the United States.

Immigration barriers between ASEAN countries also makes it difficult for EU businesses looking to come in to do business for prolonged periods of time in the region. Additionally, even if barriers to free labour movement could be overcome, it is difficult to demand uniform standards throughout the region since the levels of skills and talent pools still differed between countries. Yet, this was something more developed ASEAN nations, such as Singapore could assist in terms of knowledge transfer.

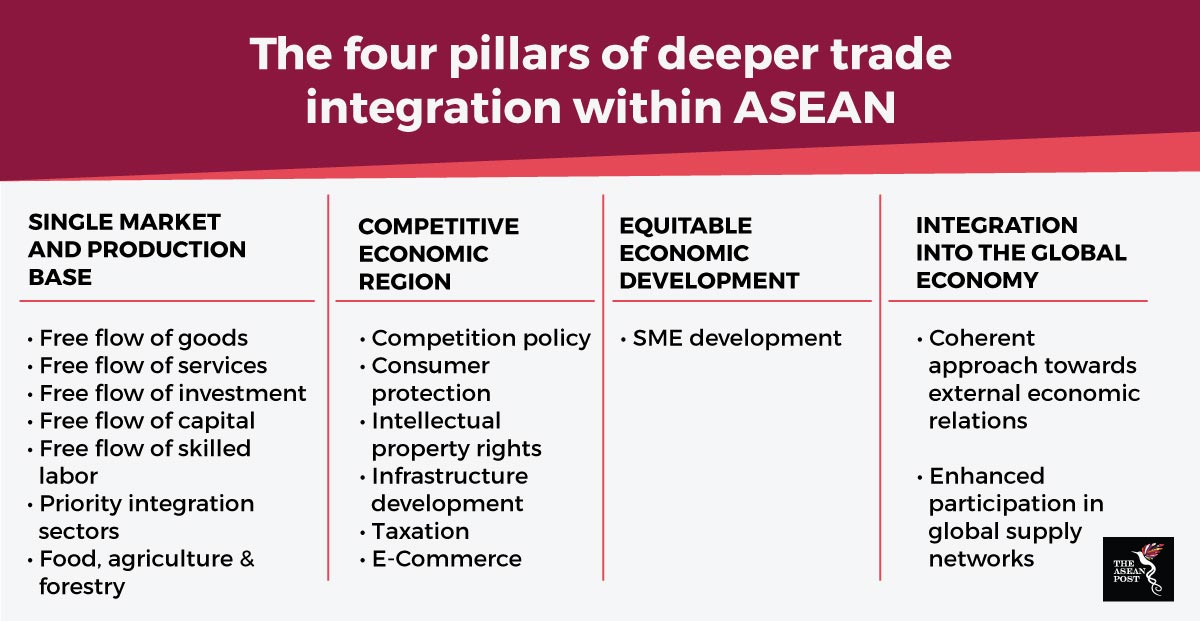

Source: ASEAN Economic Community

Stefano Poli, President of the European Chamber of Commerce Singapore acknowledged that technology talent in Singapore was at a skilled enough level to impact the rest of Southeast Asia, should there be government policies to support such knowledge transfer initiatives throughout the region.

Foreign direct investment would further increase when a legal framework was present to provide due stability. A sense of expectancy is fostered when investors are aware of the legal implications of entering and exiting investments, for example.

“We try through organizing industry working groups to put out proposals. Sometimes they’re just from our councils but many times they’re done jointly or consultation goes on between our business councils and ASEAN business councils and businesses,” said Donald Kanak, chairman of the EU-ASEAN Business Council in an exclusive interview with The ASEAN Post.

With an ASEAN-EU trade agreement in the works, surrounding issues also need to be addressed. With regards to the reported European Parliament resolution to ban palm oil, EU Trade Commissioner, Cecilia Malmstrom, was quick to point out that there were no sanctions on palm oil as yet, because the EU resolution was not in fact final.

“We have had discussions. In fact, we had very open and frank discussions with our friends from Malaysia and Indonesia. I met the ministers here and I updated them with the legislative proposals, and it is not the final outcome by the European Parliament,” said Malmstrom during a conversation with Channel News Asia.

The issue has been a sensitive one to Southeast Asia. Indonesia and Malaysia produce a combined total of 90% of global palm oil supply and could potentially affect the livelihoods of over six million people involved in supply chains surrounding the industry.

As ASEAN’s second largest trading partner, the EU too exported €118 billion worth of goods to ASEAN in 2016. Region-to-region Free Trade Agreement (FTA) talks were put back on the table in 2017, after stalling for 19 years. In the interim, the EU has managed to completed bilateral trade talks with Singapore, the outcome of which is something both parties hope to put into force by the end of 2018.

“These agreements are important in their own right but they are also part of the bigger picture. We see them as building blocks on the way to broader integration,” Malmstrom said at a forum held concurrently with the ASEAN-EU Business Summit.

Even as a regional FTA between ASEAN and the EU looks increasingly likely, no time should be wasted in fostering deeper integration within the region. The sooner this happens, the better for all parties concerned.