The discovery of 28 abandoned human-trafficking camps and multiple unmarked mass graves in the dense jungle of Wang Kelian near the Thai-Malaysia border in May 2015 sent a shock wave through ASEAN and the rest of the world. Almost 800 victims were suspected to have been held in squalid conditions, in crudely built wooden cages and barbed wire that were too small for adults to even stand in. The discovery of a pink teddy bear and other children's items, as well as bullet casings and metal chains indicated that children were also trafficked through the area and victims may have been tortured. The remains of more than 150 victims were exhumed. Autopsies revealed stories of death by starvation and disease while waiting for ransoms from victims’ families before being smuggled into Malaysia.

In July 2017, more than two years after the gruesome discovery, a Thai court found guilty 62 out of more than 100 accused on charges of forcible detention leading to death, trafficking, rape, and membership in transnational organised criminal networks. 15 Thai state officials were also implicated in the case, including a high-ranking officer, Lieutenant General Manas Kongpan. Out of the 100 accused, 91 were Thais, nine Burmese and four from Bangladesh. No Malaysians were implicated in the case. A 2017 exposé by local media identified 12 Malaysians involved in the human-trafficking case, one of whom – a local “suffering from vitiligo” – acted as the middleman.

Throughout the trial, multiple reports were made of unchecked threats against witnesses, interpreters, and police investigators. The reading of the 500-page verdicts for the more than 100 suspects by the judge took 12 hours during which he detailed the roles of each defendant in the massive criminal ring; ranging from agents and transporters to guards, financiers and overseers. Jail sentences ranging from 27 to 78 years were meted out and those convicted were also required to pay approximately US$132,000 to 58 victims. The trial was regarded as an unprecedented effort by the Thai authorities to hold perpetrators of human trafficking accountable.

The case highlighted not only the linkages between human trafficking and civil unrest and conflicts, but also the overlap between refugees, smuggled migrants and victims of human trafficking. According to a report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 63,251 victims were identified in 106 countries and territories between 2012 and 2014, although 42 percent of the victims did not cross international borders. Factors such as presence of transnational organised crime elements in the victim’s country of origin and his/her socio-economic profile could increase a person’s vulnerability to human trafficking during the migration process. According to the report, people escaping from war zones and from persecution were particularly vulnerable to human trafficking as they were more likely to make dangerous migration decisions out of desperation.

Forced brides, sham brides and child brides

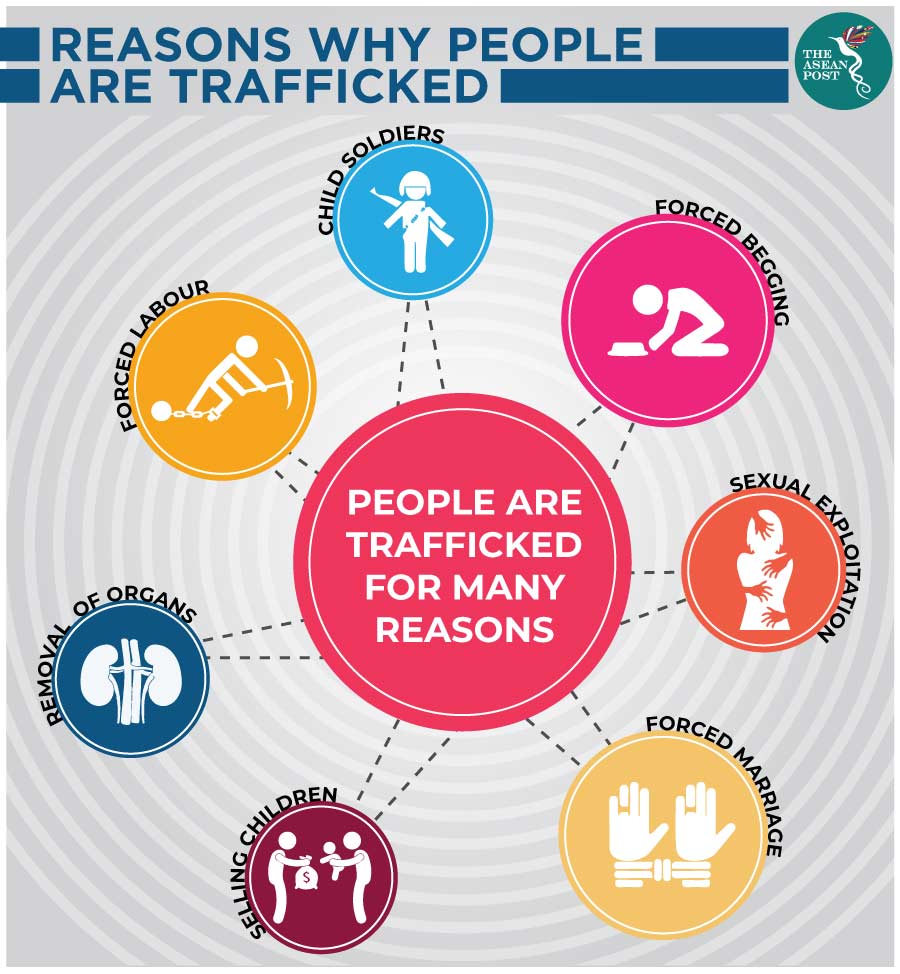

The most prominent forms of human trafficking detected by the report was for sexual exploitation and forced labour, which was reported nearly everywhere. Women especially are vulnerable to trafficking for forced marriage especially in Southeast Asia, and for sham marriages in affluent countries. Other victims were trafficked to be used as beggars, to benefit fraud, and for the production of pornography. 10 countries were also involved in human trafficking for the trade in human organs.

In East Asia, Southeast Asia and Pacific regions, most of the approximately 2,700 victims detected during the 2012-2014 period with determined age and sex were females, including a significant number of girls especially in Southeast Asia. Aside from the high number of girls trafficked, children made up almost a third of human trafficking victims in the combined regions. More than 60 percent of human trafficking victims in these regions were trafficked for sexual exploitation, while a third were trafficked for forced labour, especially in the fishing industry in Cambodia, Indonesia and Thailand. Another reason for the trafficking was domestic servitude, both within the countries of origin as well as across international borders.

“The high prevalence of females among trafficking victims is connected to the fact that women and girls are not only trafficked for sexual exploitation, but also for forced labour and other purposes. Within the broad category of ‘other’ forms of exploitation, trafficking for forced marriage was prominently detected, accounting for four percent of victims detected in East Asia and the Pacific between 2012 and 2014. Forced marriages were reported in the Mekong area, Cambodia, China, Myanmar and in Vietnam. This form of trafficking involves the recruitment of young women or girls to be sold on as wives, often abroad.”

More than 85 percent of human trafficking victims detected in East Asia and the Pacific, as well as in richer countries in the region such as Australia and Japan, were trafficked from within the region. Six percent were trafficked from South Asia, in particular from Bangladesh and India, while the last five percent were members of ethnic minorities in Southeast Asia who are stateless. Destination countries for human trafficking in the region include Australia, Japan, China, Malaysia and Thailand. Malaysia mostly received trafficked victims from Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, while Thailand detected victims from Cambodia, Lao PDR and Myanmar.

According to the report, what sets the region apart from others, is the global dimension of the trafficking flows that originate from it. Victims from the region have been detected in or repatriated from more than 60 countries in all regions and sub-regions of the world. Significant trafficking flows have been detected by many countries in Western and Southern Europe, North America and the Middle East.

United Nations (UN) Secretary General, António Guterres, in his 2018 World Day against Trafficking in Persons message said that in many cases of human trafficking, women and girls are targeted, and they end up in brutal sexual exploitation, including involuntary prostitution, forced marriage and sexual slavery, as well as the appalling trade in human organs.

“Human trafficking takes many forms and knows no borders. Human traffickers too often operate with impunity, with their crimes receiving not nearly enough attention. This must change,” said Guterres.

ASEAN governments

Every year, the United States’ (US) Department of State ranks countries around the world on the extent of governments’ efforts to meet the minimum standard as stated in the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) of 2000 for the elimination of human trafficking. The TVPA is generally consistent with the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime or the Palermo Protocol, addressing prevention, suppression and punishment for trafficking in persons, especially women and children, as well as smuggling of migrants by land, sea and air. Ranking has no implication on the severity of human trafficking in the countries.

Since its (US Department of State) previous report in 2018, things continue to look grim for ASEAN, with the exception of the Philippines. Countries such as Brunei and Cambodia dropped from Tier 2 to Tier 2 Watchlist while most countries maintained their previous placings, largely located within Tier 2. The Philippines is the only ASEAN country that managed to continue being placed in Tier 1. Myanmar performed the poorest and is placed in Tier 3.

For most of us, it is hard to imagine what it takes for a human trafficker to treat another person as nothing more than a commodity or property. However, the process of becoming such a cruel person for some offenders usually starts as being victims themselves. What makes it more difficult for trafficked persons to seek help is also the fact that their victimisation started with some level of consent although it was later trounced by fraud, coercion, deception, threats, and abuses including the abuse of power. The transectionality, complex and inter- as well as intra-regional nature of human trafficking further complicates matters.

Efforts to end human trafficking must never stop, either through legislation and international treaties, preventive actions through education and socio-economic development, or rescue of trafficked victims through various mechanisms, in countries of origin and destination. But first, we much recognise that the crime, criminals and victims exist within our own communities, and some are even entrenched within the political and cultural systems. It is after all, by any parameter, a form of modern slavery.

Related articles: