With social media already playing a role in human trafficking, arms trading and drug smuggling, it is perhaps no surprise that the illegal wildlife trade is the latest cross-border crime to go online.

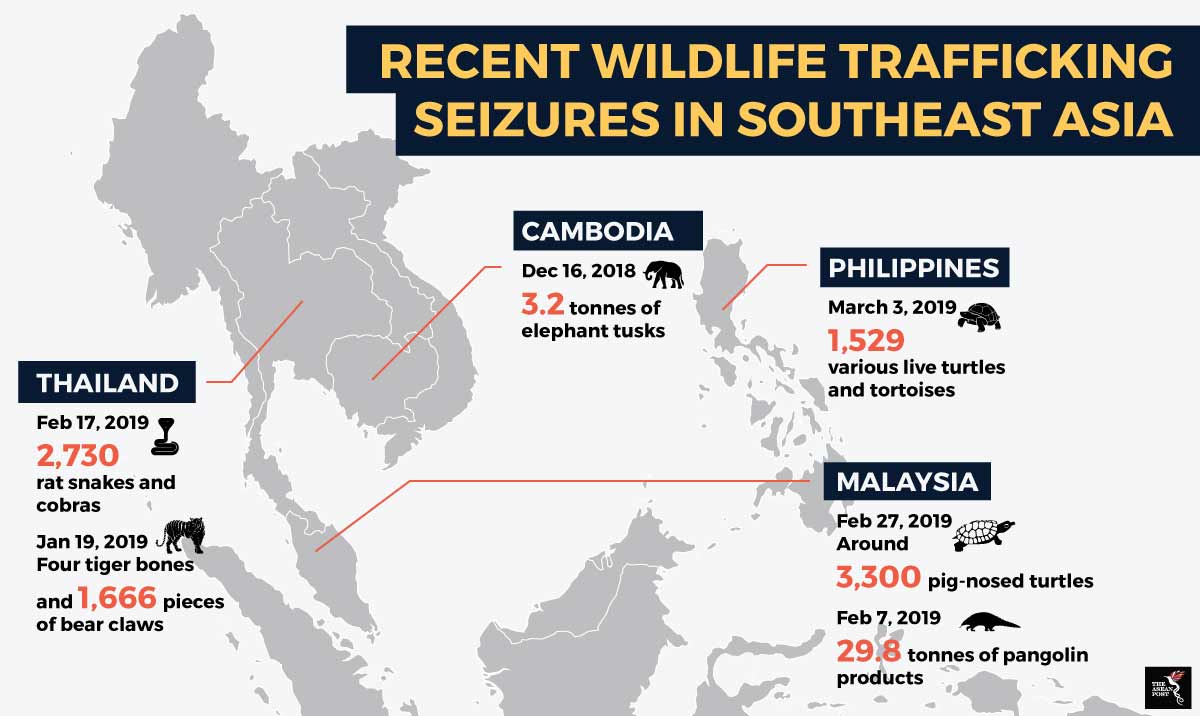

Long known as a hub for wildlife trafficking, Southeast Asia’s unsavoury reputation has been enhanced by social media – with numerous cases of buyers and sellers conducting deals while hiding behind a cloak of anonymity.

The region’s high mobile penetration rate offers buyers easy access to black market traders and vice versa, and the lack of effective monitoring combined with the popularity of social media platforms means wildlife cybercrime is a growing concern.

It marks a shift in goalposts for legislators and enforcement officers, who as it is, are hampered by a lack of resources as they try to stem a problem worth an estimated US$2.5 billion a year according to the ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity.

Southeast Asian traffickers unfazed

In 2016, CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) agreed to engage with relevant social media platforms, search engines and e-commerce platforms to address illegal international trade in CITES-listed species.

However, it seems that the international wildlife trade treaty has done little to deter Southeast Asian offenders.

In January, a man in Indonesia was arrested when his alleged involvement in illegal poaching surfaced after he posted a video of himself chopping an endangered hornbill on social media before eating it.

In the same month, a Malaysian was arrested after using social media to sell a live pangolin.

In Vietnam, a total of 3,195 ivory items in 165 advertisements from 53 sellers in 10 groups were found on social media from January to April 2017, according to a report by wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC published last December titled ‘From tusk to trinket: Persistent illegal ivory markets in Vietnam’.

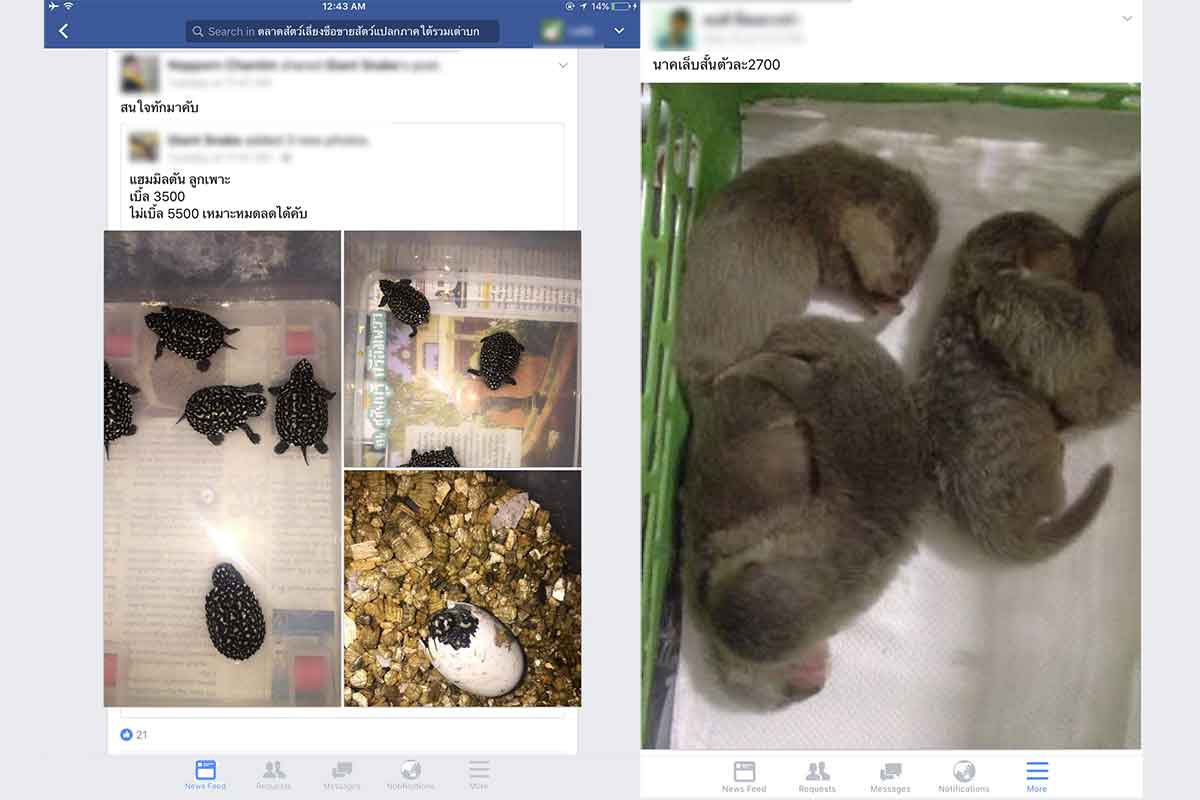

Meanwhile in Thailand, TRAFFIC found 1,521 live animals for sale online on 12 Facebook groups in 2016. Titled ‘Trading Faces: A rapid assessment on the use of Facebook to trade wildlife in Thailand’ and published last September, follow-up research on the same 12 groups in July 2018 showed that only 10 remained – but total membership had almost doubled from 106,111 to 203,445.

Among the 200 species offered for sale in the Thai report included two that are critically endangered; the Helmeted Hornbill and Siamese Crocodile. However, close to half of the species found in the report do not receive protection under Thailand’s primary wildlife law as they are not native to the country and have no legal protection or regulation.

What can ASEAN do?

The monitoring of social network platforms to weed out illegal wildlife traders is a time-consuming and resource-draining task, but technology can provide a solution to the problem it helped create.

Researchers at the University of Wyoming last year used Artificial Intelligence (AI) for wildlife image classification by first training its high-performance computer cluster to classify wildlife species by using 3.37 million camera images of 27 species from five states. Going through nearly 375,000 images, it then achieved an accuracy of 97.6 percent when identifying them – processing 2,000 images per minute, much faster than any human could.

The university has made the computer model available in a software package for Program R – a widely used programming language and free software for statistical computing.

Using this technology to scan social media platforms and send a red-flag to authorities once photos of endangered animals on sale are detected would save time and cost – especially since many endangered species are facing extinction on a daily basis.

Regionally, the ASEAN Wildlife Enforcement Network (ASEAN-WEN) which was set up in 2005 has to be revitalised. Aimed at facilitating the exchange of best practices and knowledge in combating illegal trade in endangered flora and fauna in the region, its website isn’t even functional and there have been no updates from the regional grouping for years.

One coalition which might just pull the plug on illegal wildlife trading online could be the newly formed Global Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online which counts social media giants Facebook and Instagram as among its founding members.

Formed last year in partnership with TRAFFIC, WWF (World Wildlife Fund) and IFAW (International Fund for Animal Welfare), the 21-company coalition realised that traffickers were simply shifting platforms once they were detected – thus creating the need for industry-wide cooperation.

With the goal of reducing online trafficking up to 80 percent by 2020, the coalition also includes Microsoft and Google as well as e-commerce giants Alibaba and eBay.

“Advances in technology and connectivity across the world, combined with rising buying power and demand for illegal wildlife products, have increased the ease of exchange from poacher to consumer,” said WWF when announcing the coalition.

“In partnership with the world’s biggest online companies, we're now fighting back against wildlife cybercriminals seeking to exploit web-based platforms to profit from endangered wildlife.”

Related articles:

Asia couldn't quit Facebook even if it wanted to