ASEAN’s positive economic growth has seen many changes in the way its citizens go about their daily lives. With an economy that is fast improving and the potential for progress still intact, the rise of the middle class is very much apparent within the region. An increase in disposable income has allowed some room for people to spend on items or products that might not be a necessity. As such, F&B businesses are aware of this trend and are leveraging on the fact that more people in the region are now open to the idea of eating out, an option that was once unavailable to many.

Based on a study by the Pew Research Centre, the average middle-class income in general is between 67–200 percent of the average median income. In 2012, there were an estimated 190 million people in the region who could be defined as middle class; people with disposable incomes of US$16-US$100 a day. According to Nielsen, the aforesaid number will more than double by 2020 to 400 million.

The findings of the latest study by the Thammasat Business School on the region’s middle class shows an increase in the number of people who have more disposable income. The breakdown is as follows; Indonesia – 150 million, the Philippines – 48 million, Thailand – 40 million, Vietnam – 34 million, and Malaysia – 28 million; amounting to 300 million people in total.

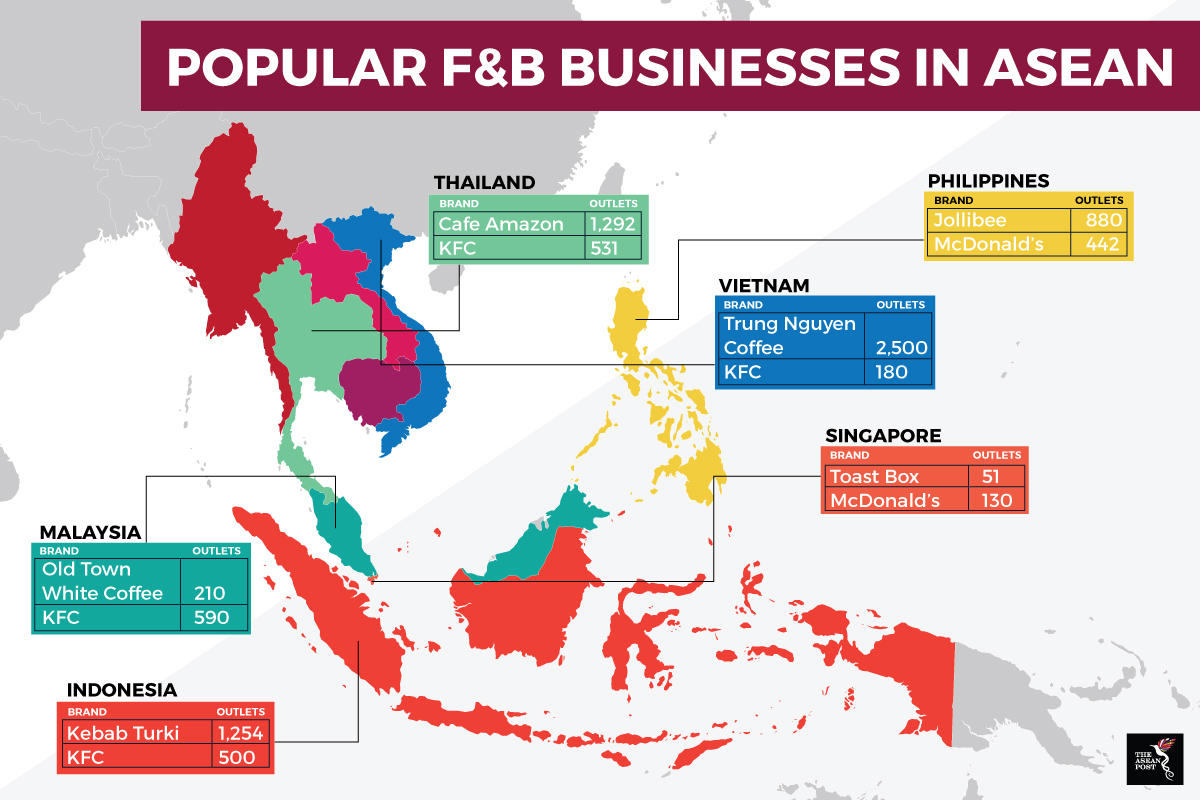

With people able to spend more, the demand for variety in terms of food will drive F&B businesses to open new franchises within the region. These businesses are aware of the potential gain that can be made by extending their operations to different locations within Southeast Asia.

Source: Various sources

Regional F&B businesses

An example of a regional player that is cashing in on the growing middle class is Marrybrown, a Malaysian quick service restaurant (QSR). As of 2017, the company has an impressive 450 outlets in 18 countries. All outlets outside Malaysia are franchised under master franchisees in the respective countries. In the region, Marrybrown has branches in Brunei, Indonesia, Myanmar, Singapore, and Thailand.

Another regional player is Dapur Penyet, an Indonesian franchise that serves ‘ayam penyet’, which translates to ‘smashed chicken’. As of this year, the business has expanded to Brunei, Malaysia, and Singapore. Founded in 2005 by Edy Ongkowijaya, Dapur Penyet also has plans to expand to the Philippines.

Southeast Asia is also more receptive of fresh produce imports, which is essentially part of the F&B industry as well. A report by the Australian Chamber of Commerce (AustCham) pointed out that approximately 90 percent of Australian firms have plans on growing trade and investment with ASEAN in the next five years. Of these, 44 percent indicated an anticipated substantial investment or growth in presence.

Australian farm exports to the 10 ASEAN nations in 2016 were valued at almost US$6.7 billion. In comparison, Australia’s farm exports to China in the same period amounted to nearly US$4.2 billion. Among the imported items from Australia include wheat, malt, milk and cream, cheese and curd, as well as meat (beef, mutton and lamb).

On the business side, there is better engagement between ASEAN and Australia after the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement (AANZFTA) came into effect in 2010. The region’s rising middle class is also seen as an important factor besides tariff reductions and greater investment opportunities. The fact that more people are able to spend on imported produce is one of the determinants to Australia’s exports to countries in Southeast Asia.

The recent expansion of F&B outlets in the region could be seen as an indicator of a growing middle class that has stronger purchasing power. The F&B industry as a whole could stand to benefit immensely in the coming years from a booming regional economy and a rapidly growing middle class.