“Where is ASEAN?”. This is the question that Charles Santiago, chairperson of the ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR), heard the most when he was in Bangladesh recently.

Earlier this year, Charles led a team of current and former legislators from Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand on a fact-finding mission to Bangladesh. The mission was to examine and experience first-hand the refugee crisis in Bangladesh following the crackdown by Myanmar security forces on Rohingya Muslims in the northern Rakhine state.

The question posed to Charles is a question that has been on people’s minds ever since the persecution of the Rohingya Muslims began in 2017.

Last year, ASEAN received strong criticism for their acquiescence of Myanmar’s actions during the 20th ASEAN Plus Three Commemorative Summit in Manila. The summit saw the attendance of leaders from all 10 ASEAN countries but only two voiced out their concerns about the situation in Myanmar. Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte also received backlash for his “Chairman’s Statement” which merely mentioned the crisis in passing.

While the Rohingya have been discriminated and targeted by the Myanmar military since the country’s independence in the late 1940s, the last exodus happened after a small faction of Rohingya militants called the Arakan Rohingya Solidarity Army attacked police posts in October 2016, killing 12 members of Myanmar’s security forces. As a result of this, the Myanmar military went on a massive crackdown targeting the Rohingya which led to many of them fleeing and seeking refuge in Bangladesh.

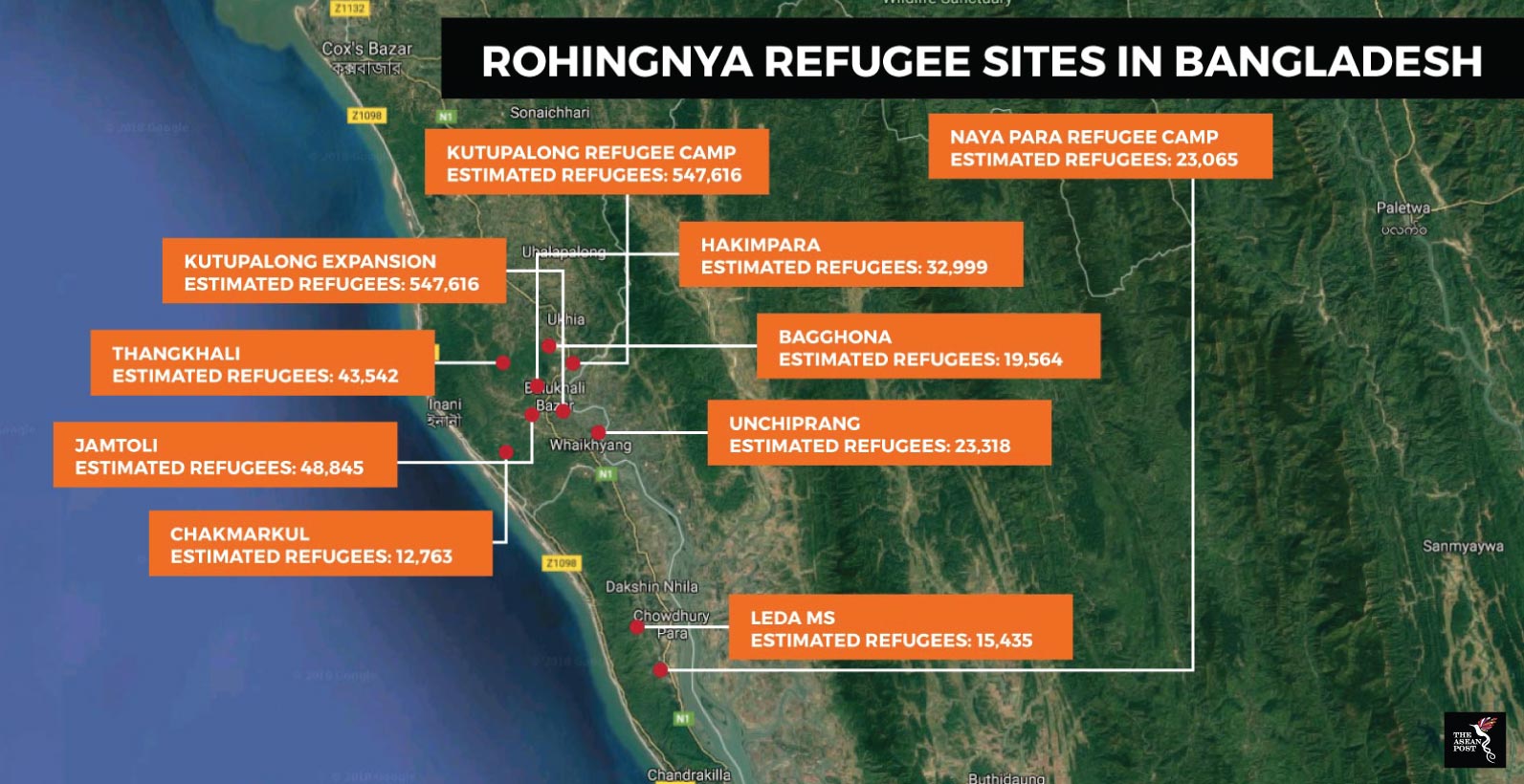

A recent biometric registration programme carried out by the Bangladeshi army to aid efforts for repatriation found that Bangladesh is hosting more than one million refugees – more than official estimates.

Yanghee Lee, Special Rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar told the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva last week that the situation in Myanmar amounts to genocide.

“I am becoming more convinced that the crimes committed following 9 October, 2016 and 25 August, 2017 bear the hallmarks of genocide and call in the strongest terms for accountability,” he said.

As a response to the crisis, most ASEAN countries have stepped in by offering aid and help to the refugees. For example, Indonesia sent 34 tonnes of aid to the Rohingya in September 2017. Some countries in Southeast Asia have also taken in Rohingya refugees.

However, many have pointed out that this is not enough and does not address the root of the issue – state sanctioned persecution of a minority group.

“Financial commitment to support humanitarian assistance is critical, but it must be accompanied by pressure on the Myanmar military to end persecution that lies at the root of the crisis,” said Rachada Dhnadirek, a former MP from Thailand who also went on the APHR fact-finding mission.

As it stands, ASEAN practices a policy of non-interference which is enshrined in its charter. While that may be true, ASEAN still has plenty of other options in dealing with this issue. Not enough leaders of ASEAN member states have come out and clearly condemned Myanmar and their leaders for the atrocities going on in the country. If condemnations are seen as counter-productive, then maybe these leaders could open up a dialogue with the Myanmar government about their policies. The silence from ASEAN leaders has been deafening.

Aside from that, ASEAN could also take responsibility by providing assistance to refugees who flee to their countries. While countries such as Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia have been taking in Rohingya refugees, their treatment of the refugees hasn’t been great. For example, Malaysia does not legally recognise refugees, so refugees in the country have a difficult time finding jobs and have almost no legal protection.

At the moment, it seems that the APHR are the only ones voicing their concerns about the situation in Bangladesh and Myanmar. ASEAN member states need to realise the gravity of the issue and take a united stand against such atrocities. Addressing the issue won’t be undermining their non-interference policy but instead it would strengthen the core principles of the ASEAN Charter.