The global population is expected to hit eight billion in 12 years. By 2050, that number will reach nine billion. ASEAN could hold the key to feeding this unprecedented number of people but only if its member countries can look beyond domestic political survival. While regional shot-callers are quick to sign multilateral agreements, the work that actually makes a difference involves engaging with 600 million or so people who live in rural areas.

To begin with, crop yields must be nutritious, bountiful, and produced with minimal environmental degradation. Before addressing climate change, there are a host of other challenges that need to be overcome. Various produce needs to be stored securely to reduce wastage. The infrastructure to get rice, cassava, coffee, soybeans and ground nuts through processing and packaging facilities swiftly have to be in place too. The drafting of mutually beneficial food pricing accords is then required to minimise the effect of existing protectionist policies. A thought also needs to be spared for the ageing farmer population.

Already in place are macro-level pacts such as the ASEAN Food Security Reserve – an agreement among member states to set aside and share rice stocks during contingency periods, the ASEAN Integrated Food Security (AIFS) Framework, and the Strategic Plan of Action on ASEAN Food Security (SPA-FS). The latter plan was implemented by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) through the Global Rice Science Partnership (GRiSP). Launched in 2010, GRiSP represents the first time a single strategic work plan for global rice research was mobilised.

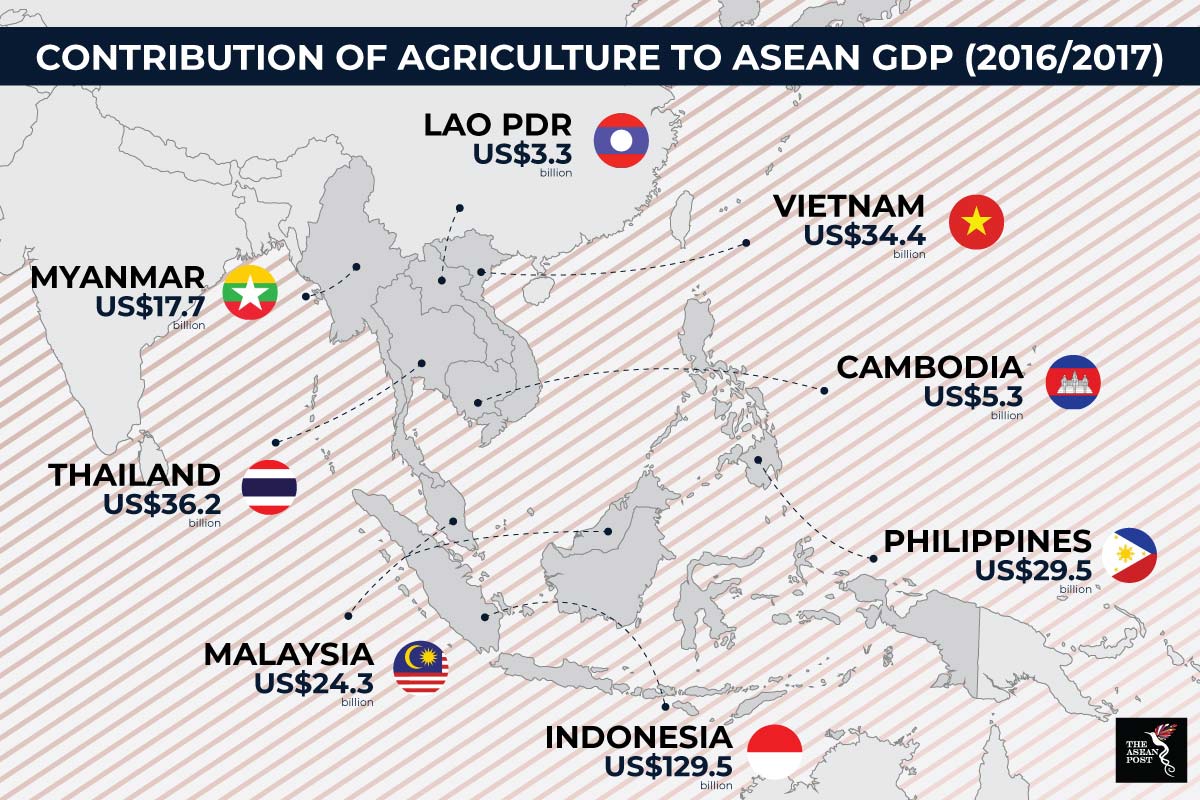

Source: Various sources

Source: Various sources

Transforming agriculture

Not only did GRiSP involve hundreds of scientists from around the world, but at the September 2013 ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Agriculture and Forestry in Kuala Lumpur, senior officials there agreed to work with the IRRI to secure the necessary resources to implement GRiSP across ASEAN.

A recent World Economic Forum (WEF) article stated that global food demand may rise as much as 40 percent by 2050. It goes without saying that increased investments, knowledge-transfer, financial inclusion and market access for farmers will increase Southeast Asia’s chances of profiting from a growing global demand. To these ends, the WEF has set up a program called Grow Asia, in partnership with the ASEAN Secretariat. The goal is to create multi stake-holder partnerships, with a particular focus on supporting smallholder farms.

To ensure sustained impetus, any brokering of partnerships between governments, companies, NGOs, civil society organizations, farmer organizations and researchers, must be led and supported by the respective agriculture ministries in the countries concerned. This is necessary to create a network of collaborations that are anchored to pragmatic KPIs, i.e. the number of farmers engaged within a given timeframe. However, due to ASEAN’s practice of ruling-by-consensus, it is sometimes difficult to take action when member states decide on a different path of action.

Consider also the numerous linkages between international trade and food security. Policies that affect exports and imports of food go a long and complex way to determining on-the-shelf prices as well as wages and incomes of workers in the domestic market. Trade, in itself, is neither a threat nor a panacea when it comes to food security, but all opportunities and risks should be assessed in detail to ensure mutually beneficial, long-term results.

Growth drivers

A 2017 report by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) stated that the ASEAN region as a whole has increased agricultural productivity at an average annual rate of 2.2 percent a year since 1991. A key driver has been the increased use of land. Across Southeast Asia, agricultural land has increased by close to 40 percent between 1980 and 2014. While these changes have contributed to increasing incomes for those employed in the agriculture sector, with positive effects on poverty and food security, this expansion has not been without significant cost to the environment.

Another important component is the role of agricultural research and development (R&D), and innovation systems. These will become increasingly important for the future of agricultural development over the next decade as higher volumes are demanded of scarcer resources. To this end, the FAO has stressed that the public provision of education and health services will be crucial for farmers to enable them to operate in an increasingly complex and knowledge-intensive industry.

With the exception of Malaysia, Southeast Asian countries tend to score relatively poorly with regard to agricultural R&D, farmer access to finance, and quality of agricultural infrastructure. Indeed, the results suggest that, compared with other sectors, agriculture in Southeast Asia may actually be underprovided for with public goods and other economic services.

Southeast Asia has the potential to become the food basket of the world. However, for this to happen there must be a concerted effort from all parties involved within ASEAN to ensure that mutually beneficial goals and targets are met.

This article was first published by The ASEAN Post on 26 July 2018 and has been updated to reflect the latest data.

Related articles:

Food security is key to SDGs success

Insuring farmers for food security