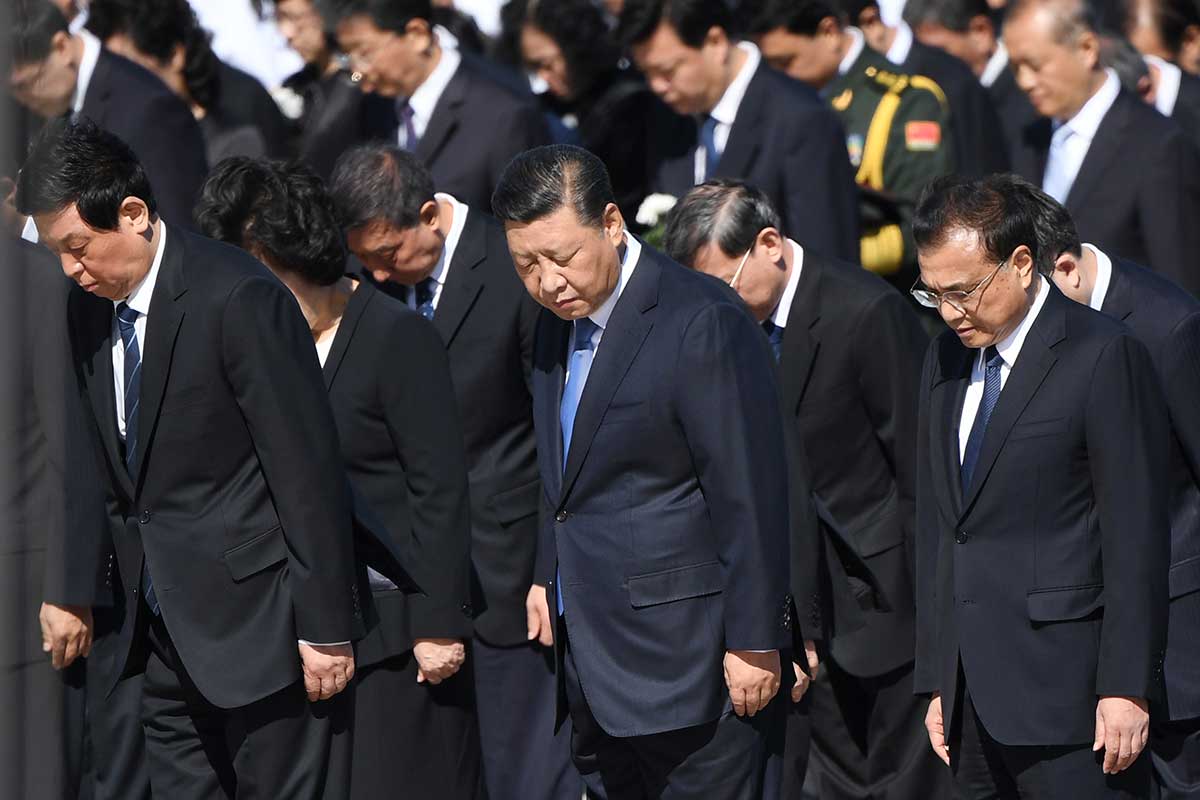

United States (US) President Donald Trump grabs the most headlines, but the cult of the strongman leader is most developed in Asia. The continent abounds with rulers – including Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and the strongest of them all, Chinese President Xi Jinping – who make a virtue of centralising power.

Obviously, leadership styles vary. But all of Asia’s strongmen share a key characteristic: they secure public support by preying on economic ignorance. In particular, they trade on the popular belief that leaders who concentrate political power are freer to guide economic growth. For the most part, people accept this claim, expecting that financial gain and “development” will be their reward.

Curiously, markets have also accepted this flawed reasoning. Global investors tend to overlook human rights, and to prefer stability and autocratic resolve to the unpredictability of democracy. Equity and currency markets regularly punish countries for even a hint of political upheaval, whereas rulers with more power and fewer checks and balances are assumed to be more capable of ensuring meaningful “reforms.”

And yet, with the possible exception of Xi, the perception that strong autocratic rulers deliver better economic results is wrong. The truth is that Asia’s strongmen are presiding over increasingly vulnerable states and even more fragile economies.

Until recently, these vulnerabilities went unnoticed. The world’s emerging markets recovered quickly from the 2008 financial crisis, and Asian economies were among the most dynamic. Only a few observers dared to point out that this rapid reversal was the result of credit bubbles fuelled by carry-trade operations hatched in overly liquid centres of global capitalism. Put another way, Asia’s post-crisis party (which was, to be honest, never that raucous) had to end sometime.

Since the start of 2018, the same emerging markets have been under intense pressure from a combination of factors, beginning with the US Federal Reserve’s tightening of monetary policy, which pulled capital back to the US. These stresses have been exacerbated by the ongoing trade war between the US and China. The resulting slowdown has exposed cracks in Asian economies that were once well hidden.

Most of the Asian leaders long feted by financial markets, it turns out, are really bad economic managers, and investors are beginning to recoil from them. But what is most striking is that it took markets so long to reach this conclusion. After all, the writing has been on the wall for years.

For example, in India, Modi’s disastrous banknote demonetisation in November 2016 should have been enough to alert observers. The move was politically successful for the ruling party but economically devastating, causing massive disruptions to the Indian economy and upending the informal sector, which employs some 81 percent of the country’s workforce.

As if that were not enough, the poorly planned and hastily implemented Goods and Services Tax should have impugned Modi’s economic stewardship. There have been other serious problems, too, like over-reliance on speculative short-term capital inflows to finance a growing current-account deficit, and inadequate attention to boosting productive employment and promoting wage-led growth possibilities. Even today, most of these shortcomings are barely being discussed.

What explains weak economic performances by Asia’s strongmen? Maybe untrammelled political power enables large-scale economic mistakes. Furthermore, while most autocrats show strength to their own public, they become meek in the face of global capital. Even when rulers rant against policies that will hurt their populist agendas – like high interest rates – they typically succumb to pressure from financial markets.

This is because the policies they have pursued have integrated their economies so completely into global trade and finance, on unequal terms. Despite their nationalist rhetoric, when the economic winds blow against them, it can be hard to change direction. The exception is China, where heterodox policies and significant state intervention have made the economy far less vulnerable to external shocks. But while Xi has thus far managed to deal with an increasingly complex and hostile external economic environment, many serious internal concerns could easily erupt into bigger problems.

Whatever the reason for Asia’s profusion of strongmen, people and markets have gotten it wrong for too long. Strongman rulers are bad for democracy, and they are really bad for the economy.

Jayati Ghosh is Professor of Economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi and a member of the Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation.