Cambodia and Lao PDR have agreed to work together to resolve pending border demarcation disagreements between the two nations. The foreign ministers of both countries have agreed to have their respective border committees meet more often to settle the matter. They also agreed to set up a coordination mechanism to help facilitate these efforts.

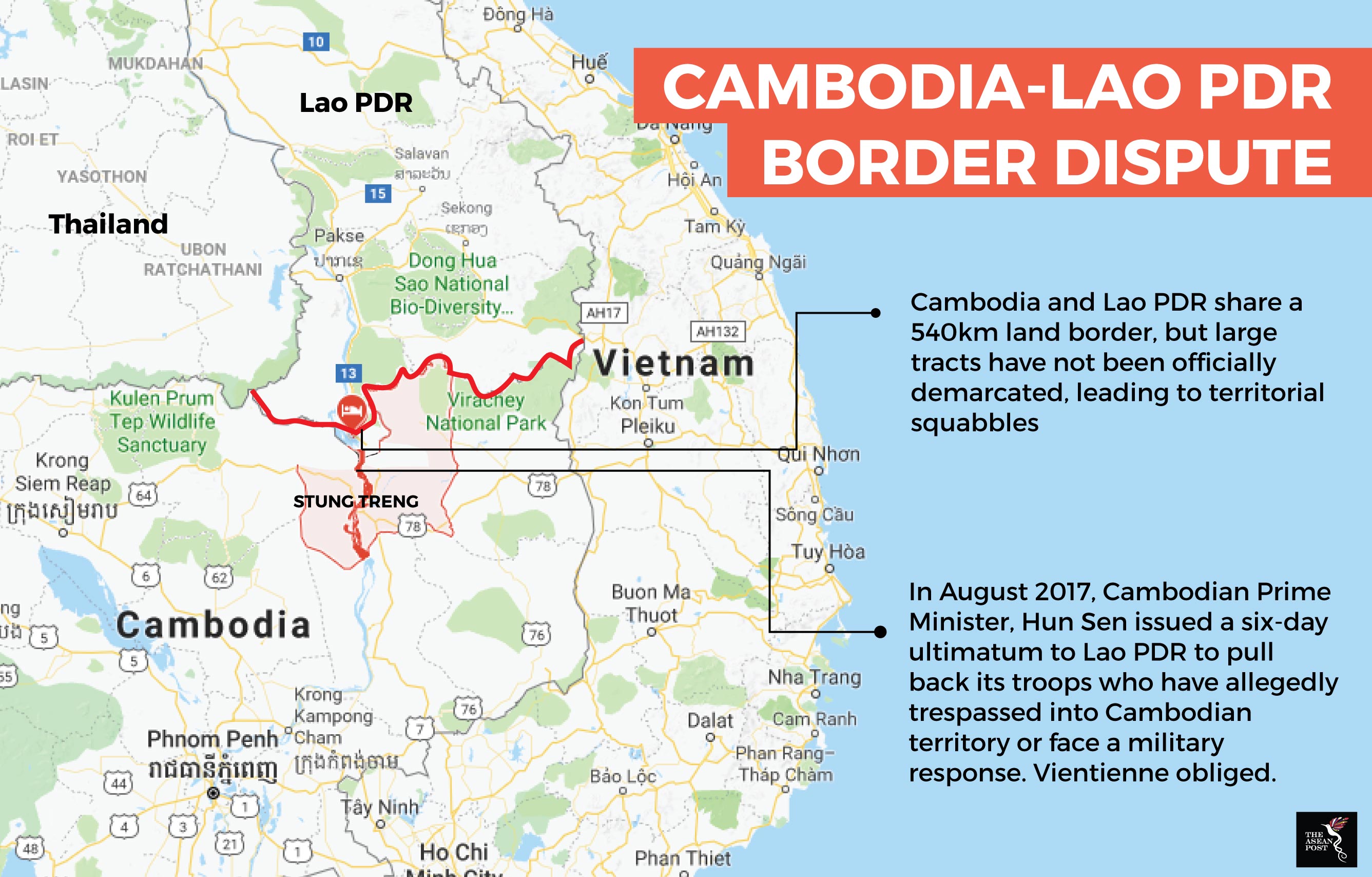

In February 2017, hundreds of Lao PDR troops breached a “white zone” to halt Cambodian military engineers who were constructing a road on what they claimed to be Laotian territory. A few months later, Lao PDR authorities shut down a border crossing in the area, claiming that their Cambodian counterparts were erecting a military outpost in an area that both nations previously agreed to keep clear of any military installations.

Four months later in August, Cambodian premier Hun Sen dispatched troops to the border to serve the Laotians with an ultimatum to withdraw after the latter’s troops were accused of crossing into Cambodian territory and refused to leave. Vientiane promptly agreed to withdraw from the area. Hun Sen also heightened tensions by citing a French colonial era map, claiming that parts of Lao PDR near the Cambodia-Lao PDR border should rightfully be part of Cambodia.

Hun Sen’s actions are widely understood by analysts as a move to flex nationalistic muscle on his side in order to gain brownie points with the Cambodian citizenry. However, events that took place throughout last year is evidence of a broader issue pertaining to the national and cultural identities of Cambodians and Laotians.

The administrative boundary separating Lao PDR and Cambodia has sustained relatively minor tensions since the independence of both nations circa the 1950s. Minor clashes and standoffs that have taken place, since, are best characterised as events rooted in irredentist feelings on both sides.

The oft-disputed area is the Cambodian province of Stung Treng, located in north-eastern Cambodia and south of Lao PDR. According to research published in the Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, many Laotians – especially the older generation – continue to assert Stung Treng as part of their country, bemoaning the decision of French colonial authorities who handed the province over to Cambodia 100 years ago at the start of the 20th century. Their claims are also substantiated by the large number of ethnic Lao first language speakers currently living there.

Source: Various sources

Khmers not only defend the technicality of Stung Treng as part of modern day Cambodia but some do contend that parts of southern Lao PDR should rightfully be part of Cambodia. Such claims are more anachronistic and date back to the Chenla and Angkor periods which saw a large presence of Khmer people in southern Lao PDR.

The research, conducted by Ian Baird, Associate Professor of Geography at University of Wisconsin-Madison attributed the border dispute to differing emphases and framings of history that has led “to irredentism and the development of identities in relation to the border.” Despite this, many ethnic Laotians living in Stung Treng now largely see themselves as Cambodians although they still hold to their cultural underpinnings. They do travel to visit friends and relatives across the border and no longer have to stifle their heritage as they did decades back during the Khmer Rouge era.

The difficulties with dispute resolution also alludes to problems arising from the demarcation of hard borders by colonial predecessors on societies that had no prior experience with such concepts.

Asian historian, Sumit Mandal explains that this is the main reason for the prevalence of disputes over territorial borders in Southeast Asia.

“State borders were imposed on fluid and interactive societies with shared histories that cannot be neatly separated. It is important that states recognise this past and the inevitability of border disputes and put their efforts into figuring out ways of resolving them,” he told The ASEAN Post in an email reply.

Resolving the Cambodia-Lao PDR border dispute will take a fair amount of political will, given that there is an ominous chance of the issue being hijacked and used to forward a nationalist narrative. With a sound understanding of the fluid nature of societies in the past and the incoherence of such notions with modern day concepts of national borders, the path towards dispute resolution should be clearer.