After the government disbanded the main opposition party, the Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP) last November, Cambodia’s opposition was thought to have quivered into nothingness, with no hope of a comeback. However, a resurgence is in the offing with the newly minted Cambodian National Rescue Movement (CNRM).

From the get go, one thing is obvious. As opposed to the CNRP, the CNRM is a political “movement” instead of a political “party” – which could mean that Cambodians may never see it on their ballot papers.

Its founder is Sam Rainsy, former president of the CNRP who fled Cambodia in self-exile, fearing arrest from the Cambodian government controlled by longstanding Prime Minister, Hun Sen. Rainsy, who was leader of the Sam Rainsy Party (SRP) joined forces with another opposition figure, Kem Sokha, leader of the now defunct Human Rights Party (HRP) and formed the CNRP in 2012 as a single opposition force to Hun Sen’s rule.

But the alliance has always been a marriage of convenience.

With Kem now languishing in prison, the CNRP dissolved and its legislators banned from politics, Cambodian opposition is literally dead. Or at least, a unified Cambodian opposition is dead. The formation of the CNRM has seemingly unpicked the patchwork cooperation between the two opposition leaders.

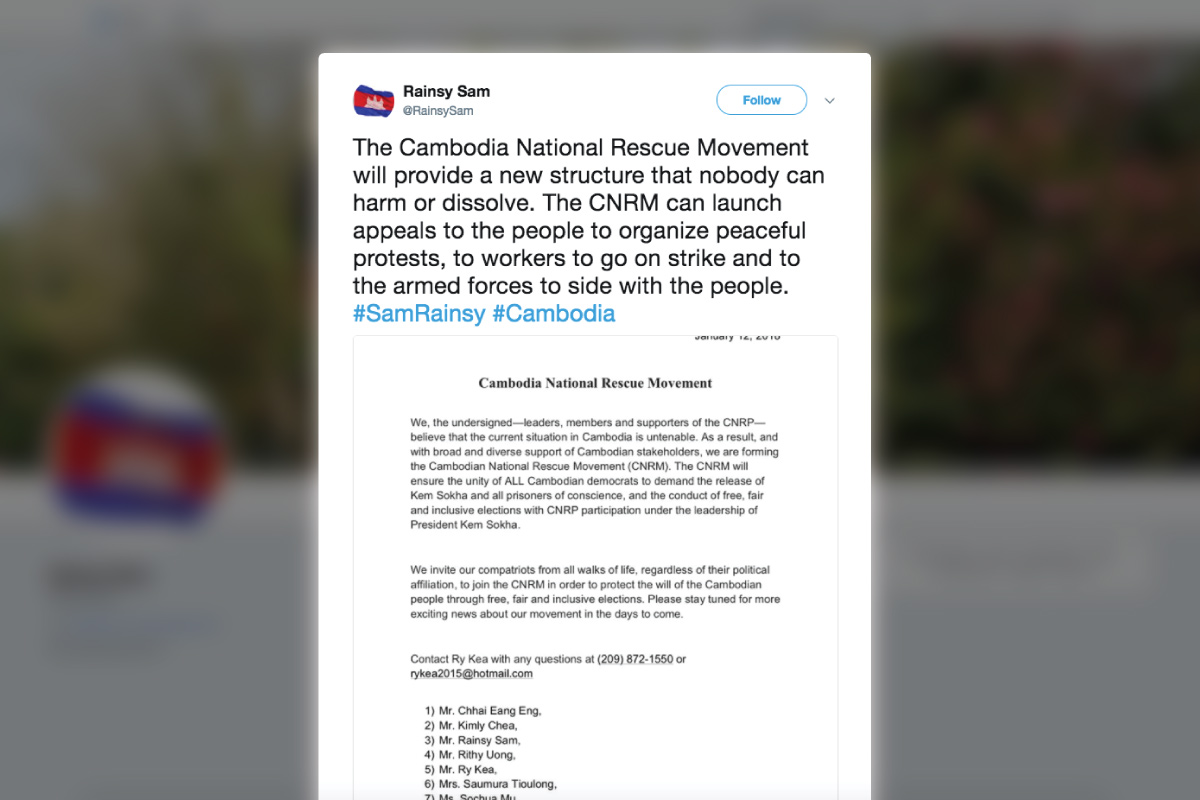

In a statement tweeted by Rainsy, the CNRM movement was described as an initiative by “leaders, members and supporters of the CNRP” whom, because of the unsound political situation in Cambodia, have come together to form the CNRM. The statement also called for the release of Kem and other prisoners of conscience and for free and fair elections to be conducted in the nation.

However, Kem has openly rejected the movement and according to his lawyers, will focus all his efforts from behind bars on the CNRP.

Whether the absence of any coordination between the two leaders of the opposition coalition was done purposefully or not, remains unknown.

According to Associate Professor of Diplomacy and World Affairs at Occidental College in Los Angeles, Sophal Ear, the situation now is one of “confusion and division.”

“Ex-SRP vs ex-HRP members of CNRP must now decide whether to join or not join CNRM. Seems the origin of CNRM suggests ex-SRP will join, and not ex-HRP,” he said in an email reply to The ASEAN Post.

Weighing in on the issue, Joshua Kurlantzick of the New York-based Council on Foreign Relations said that for a long time, both Rainsy and Kem have had trouble getting along so, an eventual split was “not impossible.”

“I don't know if it (CNRM) was formed per se to weaken the opposition, but it may well have that effect, at a time when the opposition surely cannot use any splits. It seems like many of Kem Sokha's supporters are not happy at all about the split for sure,” he told The ASEAN Post.

The CNRM which intends to hold workers strikes and peaceful protests have to be on their toes as the government is breathing down their necks. The Cambodian Interior Ministry decried them as “rebels” and an illegal organisation, sparking fears of another clampdown.

Ultimately, the brouhaha of an opposition movement for the sake of one – without cohesiveness to provide a unified front against Hun Sen – does not truly benefit the Cambodian people. It would in turn, provide Hun Sen a good opportunity to rupture the opposition once again and leave it for dead.

Ear, who is also a policy analyst, opined that whether the CNRM would be advantageous to the Cambodian populous is still unclear for now.

“If there is no unity in successor organizations to CNRP, then CNRM could end-up splitting things down the middle again. An opposition divided will be easily defeated,” he said.

But if the opposition gets its act together, the formation of the CNRM could be the first step towards a resurgent opposition in Cambodian politics. Only time will tell if that is the case.

Recommended stories: