Strategists in the West fear that China’s Belt and Road initiative (BRI) is a vast, well-laid and finely orchestrated plan to extend Chinese hegemony over much of the developing world. They should be afraid of something else: It’s nothing of the sort.

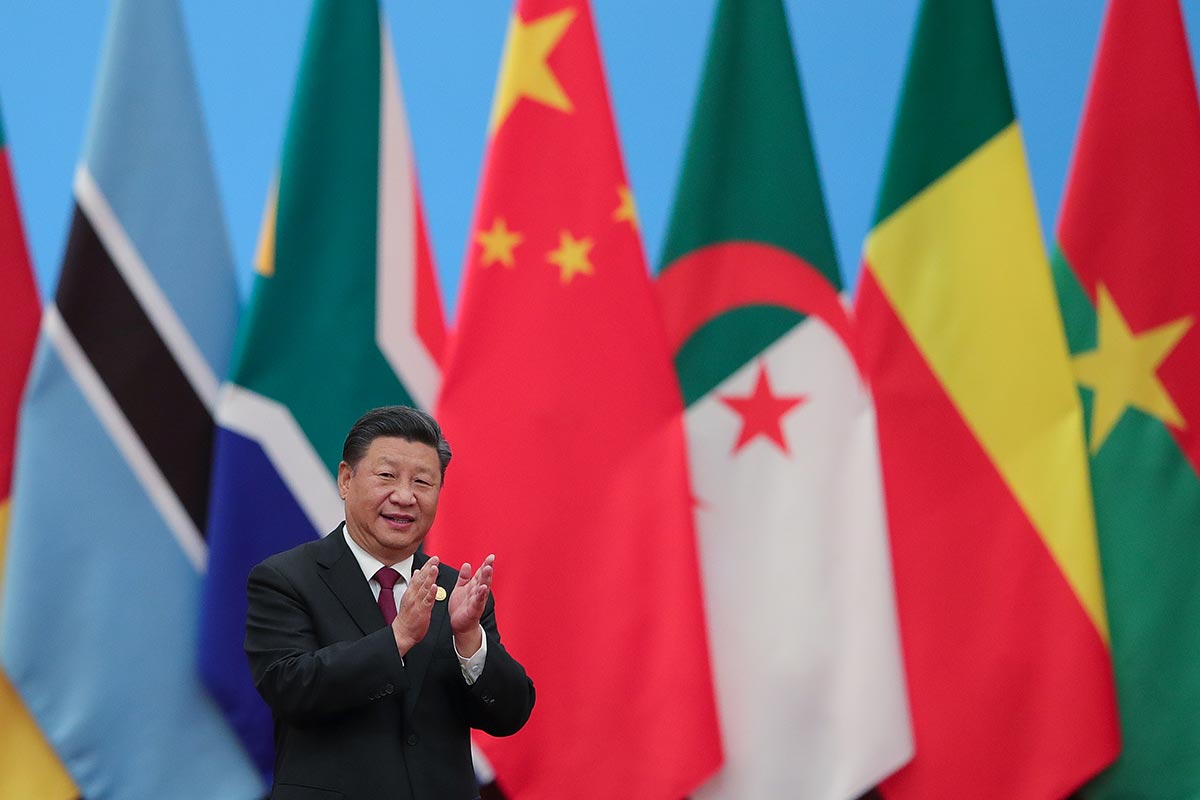

What many outsiders have missed is that the BRI is a vision, not a plan. When Chinese President Xi Jinping laid out the scheme five years ago, he proposed an ambitious transcontinental effort to link the economies of some 80 countries, covering two-thirds of the world’s population, through improved trade and transportation links. How to translate Xi’s vision into concrete deals was left to other parties, both within and beyond the Chinese government.

This modus operandi is typical in China, where the central government often issues broad directives and expects lower-ranking officials to figure out how to fulfil them. The hallmark of such communist-style mass campaigns is that everyone pitches in with frenzied enthusiasm and little coordination. Vast resources and human capital are mobilized toward one goal. Banks, businesses and officials across the country participate en masse, rather than dividing up responsibilities, as local governments rush to meet what they see as their superiors’ wishes (or, at least, to sneak through their pet projects).

Campaign-style implementation can produce remarkable outcomes. As one local official said, “A distinct feature of our political system is that we can get things done fast, especially great things.” For example, in the early decades of reform, coastal governments in China mobilized entire civil services to recruit investors using personal relationships. The effort brought in a tidal wave of foreign investment.

As often as not, though, such efforts can lead to low-quality and mismatched projects, duplication, conflicts of interest and corruption. While outsiders tend to credit Chinese leaders with long-term vision and exquisite strategizing, policy implementation has in fact often been fragmented and patchy. The negative side effects of rapid, large-scale mobilization are generally disregarded until they grow too serious to ignore.

The BRI bears all the hallmarks of just such a campaign. Five years after its inauguration, there’s still no ministry tasked to plan or monitor BRI activities. At the central level, a small “leading group” oversees the broad outlines of the project. But its “Action Plan (2015-17)” is, for an initiative that claims to involve US$1 trillion in investment — seven times what the United States (US) government spent on the Marshall Plan — stunningly thin. It’s only seven pages long, if printed in large font, and includes directions such as “share responsibilities and progress together” and “plan collectively but go where the demand is.”

This is hardly a blueprint for how to invest US$1 trillion, by when, for what priorities and by whom. Top officials still haven’t defined what constitutes a BRI project or who qualifies as a participant in the initiative. As a result, every investment project, whether public or private, profit-making or money-losing, honest or dishonest, claims to be part of the bandwagon. A recent New York Times report noted that BRI projects to “win friends” include ski slopes, spas and amusement parks.

What’s more, this particular campaign is a high-level, national effort on which Xi has staked his personal legacy. It’s therefore mobilized not only all segments of the party-state bureaucracy and media, but also Chinese society, including private companies, universities, think tanks and consultancies. Given the sums involved and China’s increasing diplomatic clout, it’s also drawn the participation of foreign companies, foreign media, international development agencies and governments around the world.

China has never expanded one of its campaigns overseas before and wasn’t prepared for the bureaucratic challenges it would face. Similarly, its international partners are for the most part novices at dealing with Chinese companies and banks. The result has been mass confusion coupled with hits and misses. Pressured by Belt-and-Road fever, state companies have taken on projects hastily and given out loans whether or not they’re financially viable.

Some deals have soured. Not all Chinese overseas investments are state-funded; private investors and even ethnically Chinese investors who aren’t from China are involved as well. Yet, most observers lump together Chinese-looking actors as “China.” So, if any of them blunders, the blame goes to China.

Western critics of the BRI have assumed that the failures are intentional, part of a strategy of “debt-trap diplomacy” to ensnare other countries in debt and seize strategic assets from them. “It is even better for China that the projects don’t do well,” Brahma Chellaney, the pundit who first used the term, has asserted. Proponents of this theory cherry-pick instances of failure as proof of China’s insidious intentions and ignore examples such as Cambodia, where borrowing has been prudent, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The real danger is different: The BRI has become a global investment campaign on steroids, where too many people are too eager to spend and build without sufficient care. The initiative may yet deliver growth opportunities for many developing countries. But, for it to encourage “common prosperity” instead of debt and bad publicity, China must exercise greater selectiveness, coordination and transparency. The BRI isn’t a master plan: It needs one. – Bloomberg