The current period of sustained economic growth in Southeast Asia is expected to continue into the foreseeable future. Analysts are projecting the cumulative growth of economies in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to be upwards of 5.1 percent for this year. This situation has rightly prompted a rise in energy demand within the region. According to the ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE), electricity demand in ASEAN is expected to grow by approximately 5.5 percent yearly between 2016 and 2020.

To meet the growing demand for energy, huge investments in power generation capacity will be required. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that it will cost ASEAN governments nearly US$990 billion to develop its power sector through to 2035. In order to fully maximise such a substantial investment, ASEAN governments understand that they cannot afford to take a siloed approach to the issue and instead have begun to plan for a regional power grid infrastructure.

Established in the late 1990s, the ASEAN Power Grid (APG) represents a forward-thinking vision to enhance cross border electricity trade in the region which would help undergird rising electricity demand. Tasked with realising this ambitious vision is the Heads of ASEAN Power Utilities/Authorities (HAPUA). Through the ASEAN Power Grid Consultative Committee (APGCC), HAPUA aims to develop a common ASEAN policy on power interconnection and trade which would subsequently lead to the realisation of the APG.

Progress on the grid

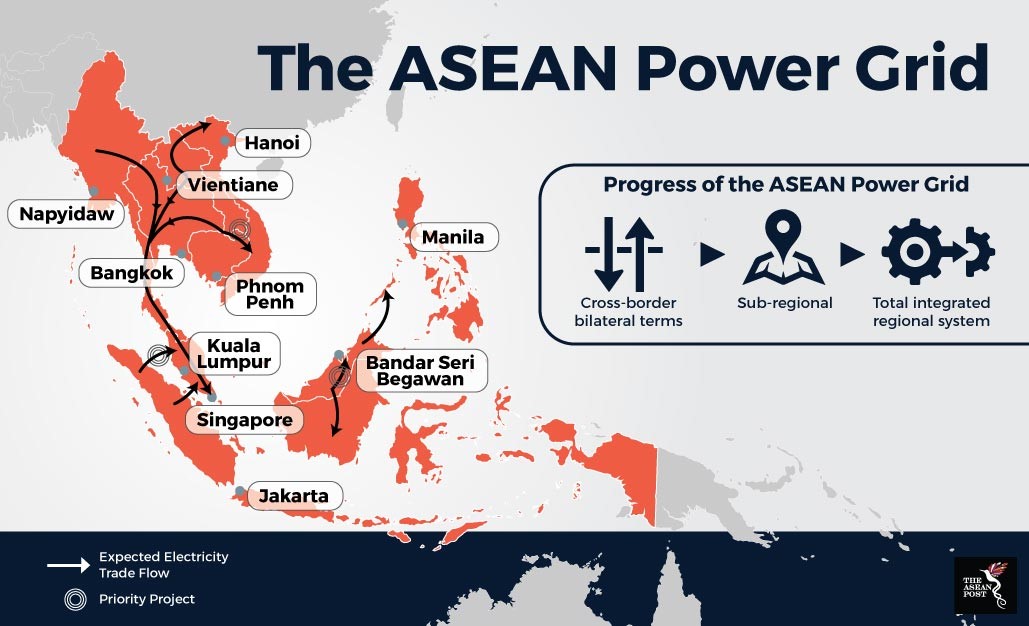

The final form of the APG will encompass all the 10 members of ASEAN, divided into three sub-systems. The Upper West System, located in the Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS) will encompass Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam. The Lower West System will cover Thailand, Indonesia (Sumatra, Batam), Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. The East System will include Brunei, Malaysia (Sabah and Sarawak), Indonesia (West Kalimantan), and the Philippines.

However, construction of the APG is reflective of a gradual and incremental development strategy. Power connections will first be developed on cross-border bilateral terms, then expanded to a sub-regional basis before being augmented into an integrated regional power architecture.

Thus far, the interconnection projects are on a cross-border bilateral basis. Eight out of 16 projects have been implemented with a power exchange and purchase of 5,200 megawatts (MW). However, HAPUA announced last September that three priority projects are being pursued which would double the exchange and purchase of electricity to 10,800 MW in 2020 – and beyond 16,000 MW post-2020. These planned projects will connect power grids between Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatera, the Malaysian state of Sarawak and Brunei in Borneo, as well as Lao PDR and Cambodia.

For the APG to truly resemble a regional power architecture, it must move beyond bilateral exchanges of power towards multilateral power interconnections. The implementation of the first phase of the “Lao PDR-Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore (LTMS) Power Integration Project (PIP)” in January this year is a step in the right direction.

Last year, Malaysia inked an Energy Purchase and Wheeling Agreement (EPWA) with Lao PDR and Thailand. The deal will see Malaysia purchase up to 100 MW of hydro power from Lao PDR via Thailand’s existing transmission grid starting this year. This would prove beneficial to Malaysia due to the competitive pricing compared to other sources. The purchased 100 MW would serve as a reserve source of energy which will also enable Malaysia to improve its share of renewable energy which currently stands at 22.5 percent of its total energy mix.

Challenges at hand

The main challenges to the APG are in terms of legality, technical expertise and financial modalities. Hence, HAPUA must swiftly develop a legal framework as a predominant guide towards realising the APG. Prevailing overlapping claims on territories are a hampering factor when it comes to promoting freer cross border energy trade.

HAPUA has also expressed its intention to cooperate with the ASEAN Energy Regulatory Network (AERN) to conduct various studies including areas like Taxation and Tariff for Cross-Border Transaction, and Regulation on Public-Private Participation. Such initiatives would prove to be important in financing large scale power projects. In this aspect, an adequate legal framework will also prove vital as the more developed countries within ASEAN can engage in knowledge and technical transfer with some of the lesser developed nations when it comes to APG projects.

HAPUA has already elicited success in its cooperation with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) to develop technical standards and financing models for countries to consider when advancing their respective power systems. It is important for such standards to be homogenised as interoperability would vastly improve the efficiency of cross-border electricity trade.

An integrated power grid within ASEAN would be a silver bullet that ensures reliable electricity access for its citizens. If done correctly, it not only would set the standards for regional cooperation within ASEAN but help member states reap the economic benefits that would follow.