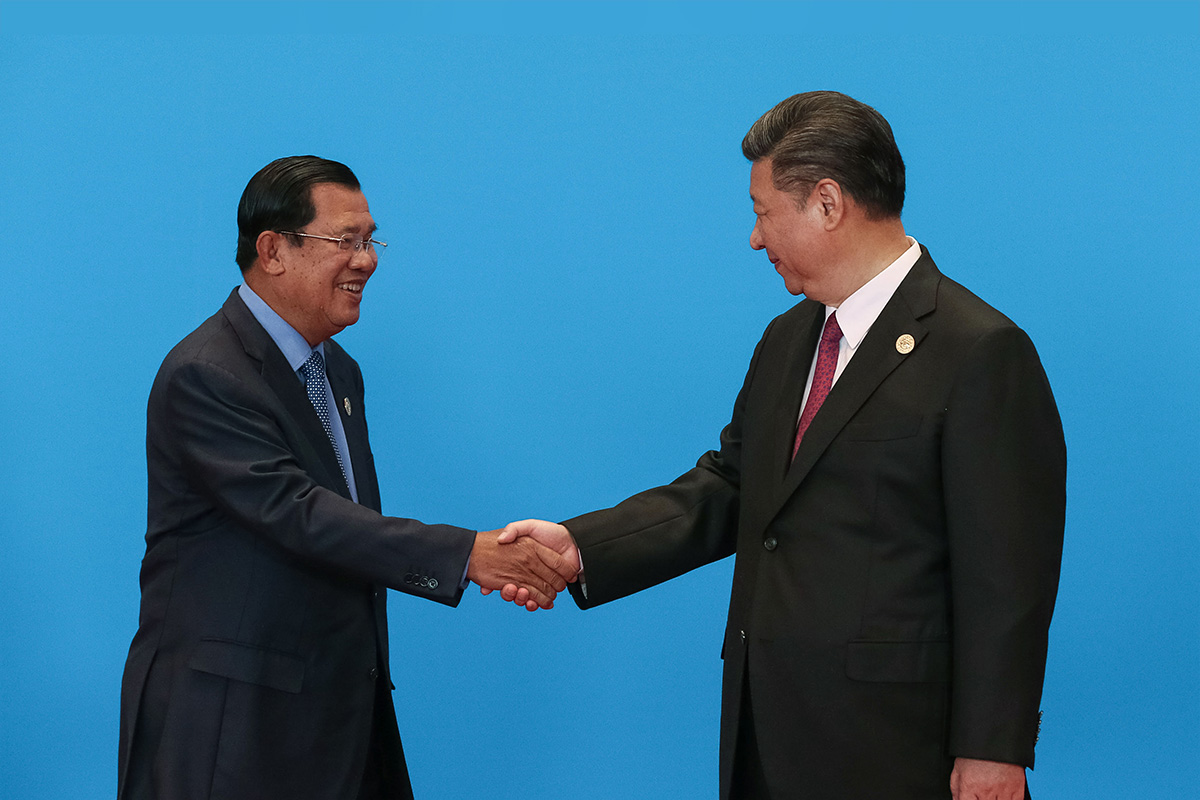

Cambodia and China recently marked 60 years of the establishment of diplomatic relations with a grand gala dinner. Presiding over the event were Cambodian Prime Minister, Hun Sen and Chinese ambassador to Cambodia, Xiong Bo.

Both countries established formal diplomatic ties in July 1958 and have since elevated ties to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Cooperation in 2010. Phnom Penh’s close relations with Beijing has its roots in the 1990s, in the aftermath of the Cambodia-Vietnam war.

China initially backed Hun Sen’s opponent, Norodom Ranariddh, President of Cambodian royalist party, FUNCINPEC. However, when Ranariddh began to cosy up to Taiwan, Beijing grew friendlier towards Hun Sen who eventually ousted Ranariddh.

At the time, Hun Sen was faced with increasing international isolation after his coup and turned towards China who opposed the sanctions by Western democracies on Cambodia. He suspended diplomatic relations with Taiwan and threw his support behind the One China policy which sees Taiwan as a breakaway Chinese province that would be reunified with mainland China one day.

Western sanctions lasted for 10 years and ended following the decision by the Obama administration to normalise relations with Cambodia during his first term in office. Nevertheless, that did little to change Hun Sen’s negative perception of the United States (US) and the West in general for their tendency to act on a moral high ground with regards to human rights and basic freedoms.

Hun Sen hailed his relationship with China, calling them Cambodia’s “great friends” and enjoys Beijing’s continuous backing amid his domestic crackdown on dissent. Western countries like the US and France have been critical of Hun Sen’s spate of rights abuses over the past few months which has seen the dissolution of the main opposition party as well as the jailing of key opposition figures and the stifling of press freedoms.

In a recent speech, Hun Sen singled out the US and France stating that if they were unhappy with human rights conditions in Cambodia, they should stop sending aid to the country. He also chastised the democratic principles of the US for the cost of human lives they exacted during the Pol Pot era in the 1970s and stated that they should rightly pay Cambodia US$20 billion in compensation.

Chinese aid and investments

Over the years, Phnom Penh has been receiving foreign aid from Beijing. The latest came in the form of US$100 million to help modernise Cambodia's military. Such financial assistance comes with no strings attached, as compared to Western aid which is usually given on the guarantee that the recipient adheres to a particular set of democratic values.

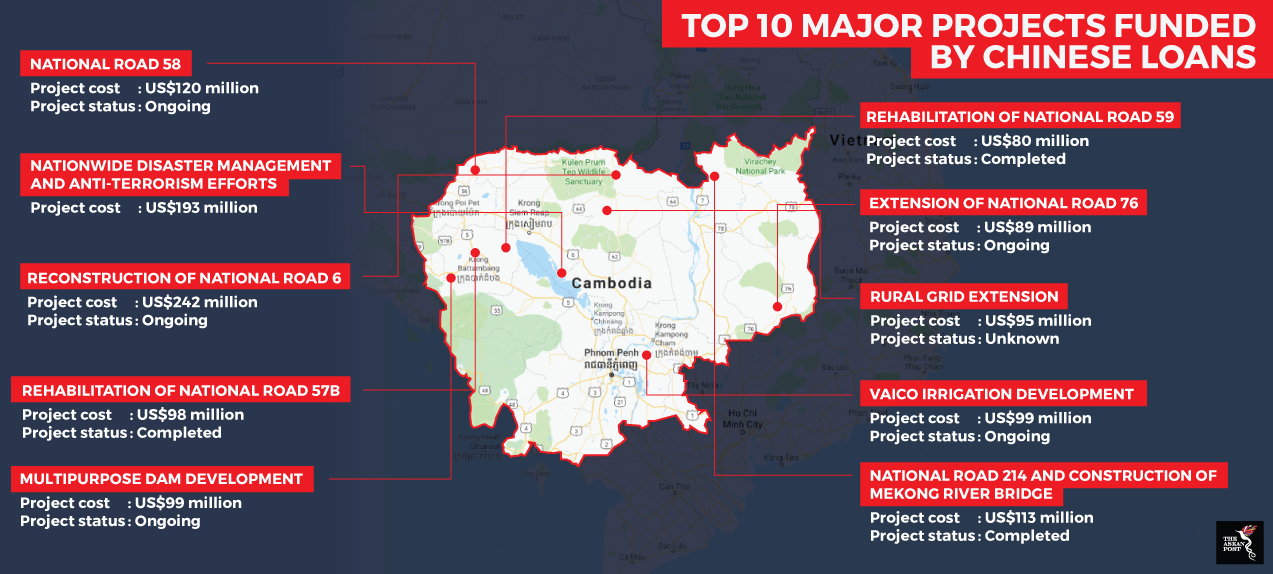

Source: Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC)

Cambodia is also a key beneficiary of infrastructure projects under China’s trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). These projects are financed by Chinese loans and executed by Chinese companies. Some observers have viewed this way of doing business as China’s way of maintaining leverage in the event countries are unable to service their loans from China.

However, Cambodia remains unfazed over the prospects of being ensnared by China’s “debt-trap diplomacy.” The BRI is said to complement Cambodia’s own five-year strategic development plan, called the Rectangular Strategy. Together, both agendas are set to accelerate Cambodia’s economic growth as well as provide opportunities for Chinese companies to invest in and develop Cambodian industries.

Since overtaking Japan as the largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI) – by investing around US$12.6 billion by end-2017 – China’s influence has only increased in the country. Chinese money is being used to develop national roads, power plants, and special economic zones dedicated to technological innovations.

In January this year, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang inked 19 agreements with an undisclosed value but is estimated to be worth billions of US dollars. It included deals to construct a new airport in Siem Reap and a highway to connect Phnom Penh to Sihanoukville which is increasingly becoming a hub for Chinese investment.

Phnom Penh’s ties with Beijing is set to only grow closer over the coming years given Hun Sen’s almost certain re-election in 2019. His opponents, some of whom have been wary of China’s intentions have been all silenced.

Nevertheless, Cambodian foreign policy is poised to be tested amid a challenging regional environment. The reduced presence by the US in Southeast Asia should not serve as an invitation to completely shift its foreign policy posture towards China. Instead, it calls for a rethinking of traditional diplomatic strategies in order to adequately accommodate present-day diplomatic realities but not step on the toes of any one power or ally.

Cambodia is on a risky path – having already been branded by many as a Chinese client state. This could have repercussions on neighbouring Southeast Asian nations, many of whom still hold steadfastly to the principle of centrality, a principle which is fast disappearing in Cambodia under Hun Sen’s rule.