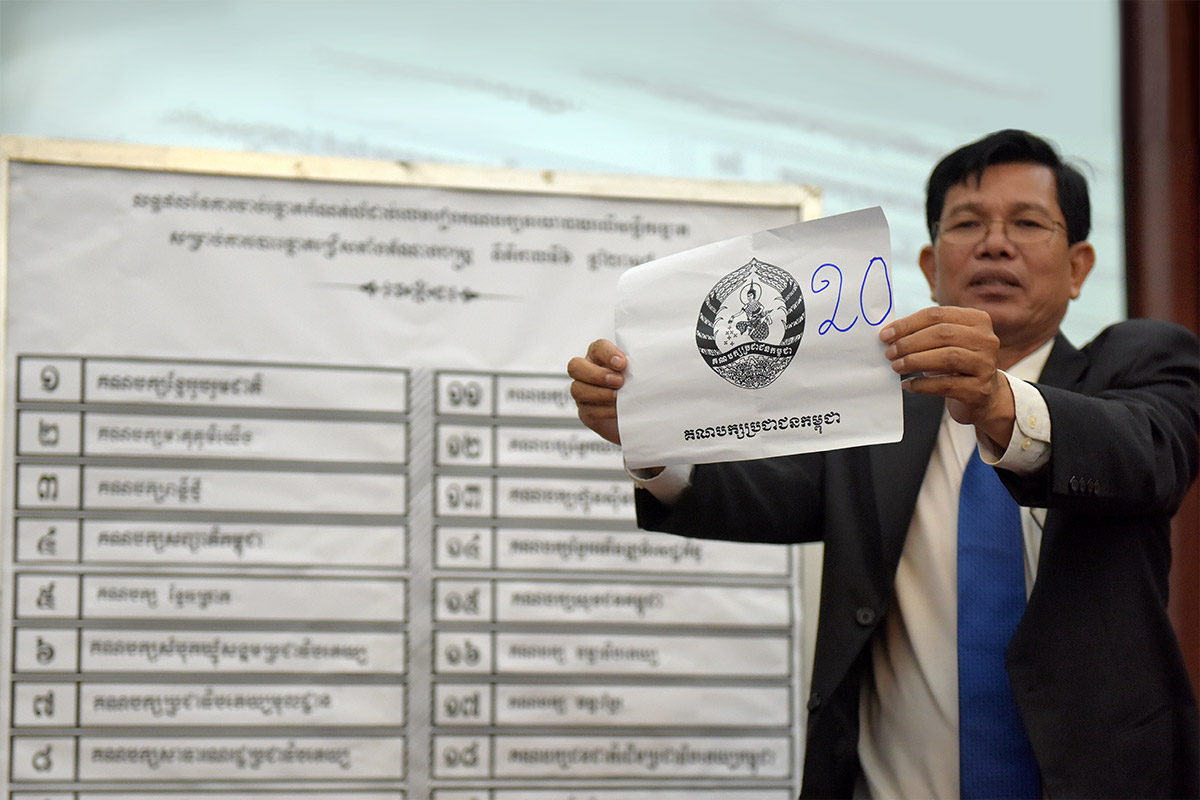

Cambodia’s ruling party, the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) threatened legal action against a campaign started by opposition members which called for voters to boycott a national election slated to take place in July. The ‘clean finger’ campaign represents a last-ditch effort by the now dissolved opposition party that has slammed the upcoming elections as a sham.

In recent weeks, several opposition figures have taken to social media to post up pictures of themselves holding up a “clean finger” as a symbol of the boycott. In Cambodia, voters must dip their finger in indelible ink after casting their ballot – a practice adopted by many countries in order to stymie electoral fraud.

The CPP has warned that the move to encourage voters to skip the polls was akin to “incitement to obstruct an election” which could be met with criminal charges.

“Courts can take legal action. According to election law, people who obstruct an election can be fined and face criminal charges,” party spokesman Sok Eysan told Agence France Presse (AFP).

Voting, however, is not compulsory in accordance with Cambodian law.

“We are calling on them not to dirty their hands in this fake election,” Sam Rainsy, a former opposition leader, now living in exile in France, said in a tweet earlier this week.

Rainsy also alluded to the near impossible task of the current group of small opposition parties to monitor the upcoming elections. The opposition in the past was able to field almost 40,000 observers in previous elections to flag electoral abuse, he said.

“It's impossible for the new small parties to do the same in the upcoming fake election. Don't Vote, Don't Monitor,” his tweet read.

Legal proceedings

Earlier this week, Justice Minister Ang Vong Vathana ordered the Phnom Penh Municipal Court prosecutor to initiate legal proceedings against Sam Rainsy under new lèse-majesté laws. This was in response to his comment on the veracity of a letter issued last week by King Norodom Sihamoni, urging Cambodians to participate in the vote.

Source: Various sources

In response to the government’s actions, a group of United Nations Special Rapporteurs focusing on human rights and basic freedoms released a statement calling for Cambodian authorities to respect the political freedom of its people, including the option of abstaining from voting.

“While both Cambodian and international human rights laws rightly prohibit intimidation or coercion of voters, a call for boycott of an election neither coerces nor intimidates, nor does it, of itself, affect public order. Instead, it leaves voters free to decide whether to participate or not,” the experts explained.

A group of regional lawmakers from the ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights condemned the CPP’s threats with one member, Tom Villarin, a Philippine Congressman saying that an election “without a viable opposition will be a farcical exercise.”

“In such a situation, refusing to vote must be recognized as a legitimate right and a form of affirmative political choice to show disapproval of the electoral process,” Villarin said.

The lawmaker, who also sits on the Philippine House Committee on Human Rights further called on international organisations and governments to refrain from sending observers to the elections which may then be perceived as lending credence to an illegitimate election.

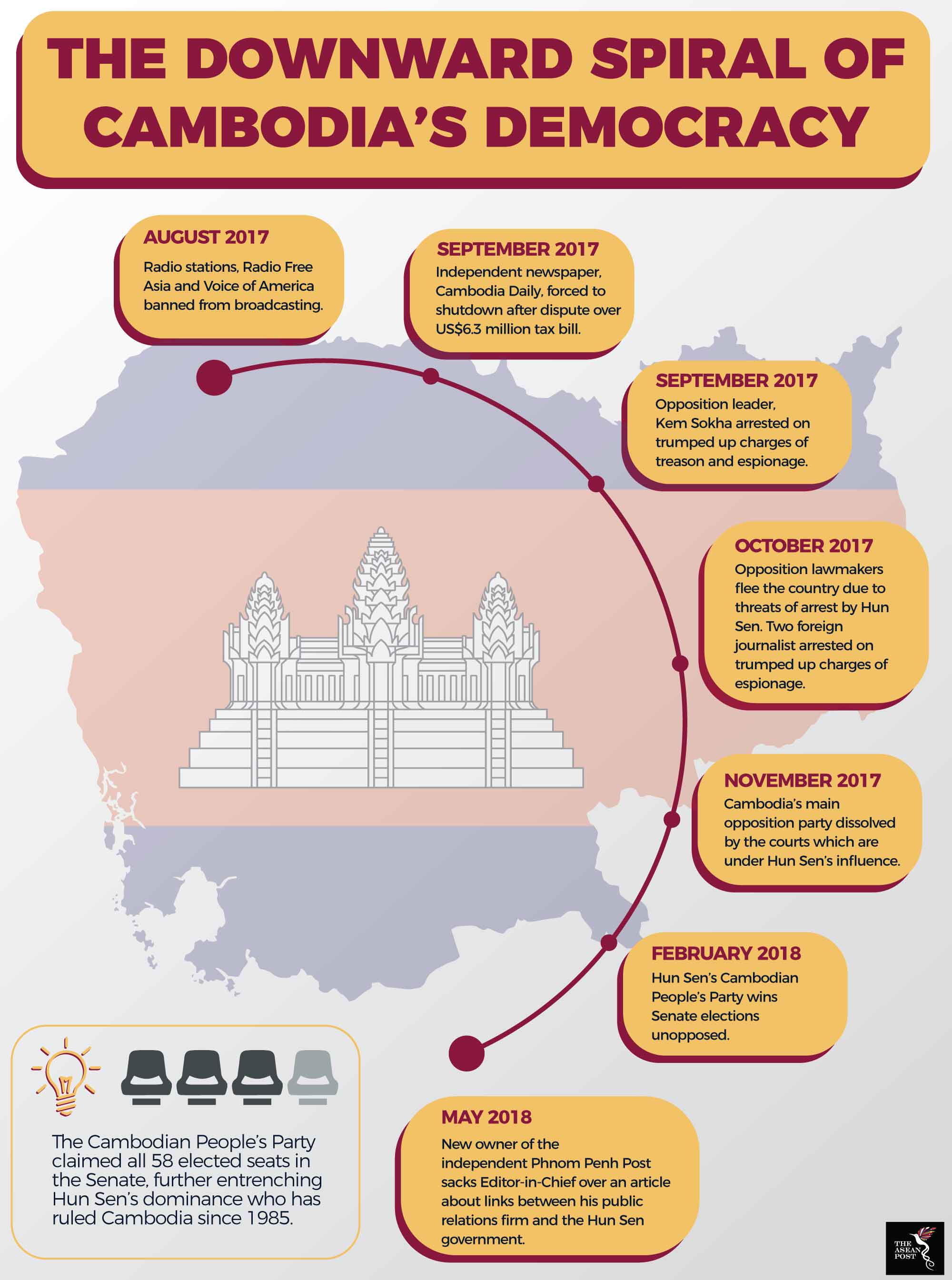

Cambodia has dominated the headlines over the past few months for all the wrong reasons. This young Southeast Asian democracy is only democratic on paper – having been under the 33-year iron fisted rule of Hun Sen, who had previously defected from the Khmer Rouge.

Hun Sen’s onslaught against his detractors kicked into high gear towards the end of 2017 with the arrest of opposition leader, Kem Sokha, the shutting down of The Cambodia Daily, a prominent English newspaper and finally the complete disbandment of the opposition party which had been gaining ground since May last year.

When the international outpouring of outrage ensued, Hun Sen remained undeterred, knowing well that he has the continuous backing of China. Chinese aid, which comes with no strings attached - unlike aid from the West - has been pivotal to Cambodian economic development as well as lining the pockets of Hun Sen’s family members who own most of the corporations in the country.

“Elections should be about fulfilling the hopes and aspirations of the people,” Villarin added. “The way things are proceeding in Cambodia, it would seem that the people’s aspirations are at the bottom of the government’s list of priorities,” he concluded.