“To dignify what happened as “polls” is to give them too much credit. The Soviet Union also held elections. No-one believes they were free and fair.”

That was Associate Professor of Diplomacy and World Affairs at Occidental College, Los Angeles, Sophal Ear’s reaction towards Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen’s sweeping victory in last week’s Senate elections.

Cambodia has dominated the headlines over the past few months for a variety of reasons. Economically, it is on an impressive growth trajectory – upwards of 7 percent according to estimates by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). However, the country’s slide to absolute authoritarianism has sullied its name in the international fora.

Hun Sen’s onslaught kicked into high tempo towards the end of 2017 when he arrested opposition leader, Kem Sokha, shut down prominent English newspaper, Cambodia Daily, and disbanded opposition party, Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP). These events proved to be the final nail in the coffin for Cambodian democracy and ensured that Hun Sen’s 32-year rule would continue uninterrupted. When the international outpouring of outrage ensued, Hun Sen remained undeterred. The CNRP were gaining ground in previous local elections and with the Senate (upper house) and National Assembly (lower house) elections looming this year, he wasn’t taking any chances.

How important is Hun Sen’s win?

On the surface of it, the Cambodian Senate has no real legislative power unlike the National Assembly. Yet, the Senate election process is a foretaste of what is to come when general elections are held.

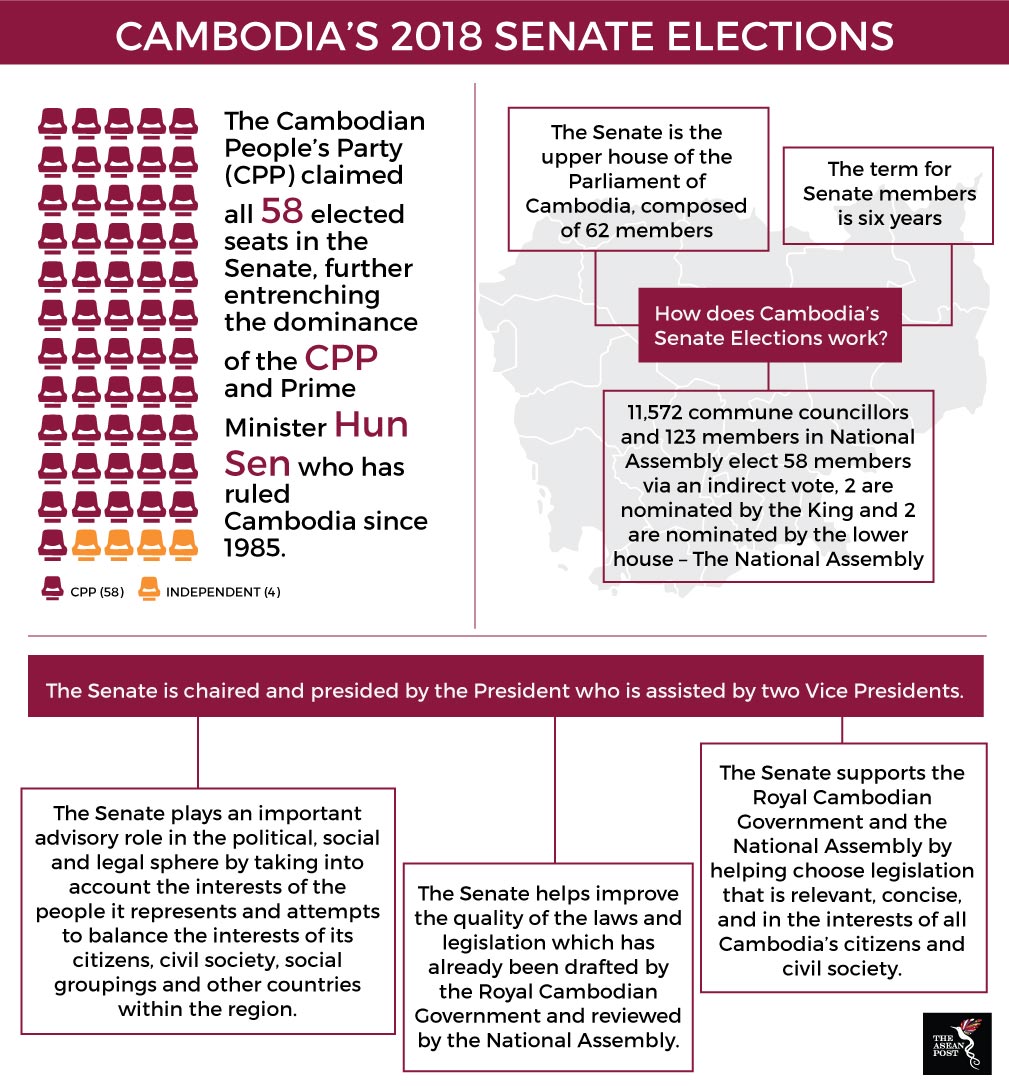

Cambodian senators are elected indirectly by local councillors whom themselves were previously elected by the masses during the local elections in June 2017. However, after the opposition was disbanded in November 2017, the opposition councillors were stripped of their positions. Their seats were distributed to the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) and other minor parties which are said to be under the thumb of the CPP.

According to David Hutt, a Southeast Asia-based journalist and columnist, if the opposition had not been dissolved, the outcome of the recent Senate elections could have been very different indeed.

“Mu Sochua, one of the CNRP’s vice-presidents, said that the Senate was the “crown prize” after last year’s commune election. What she meant, I think, was that if the CNRP hadn’t been dissolved then it could have taken a significant share of Senate seats. If this scenario had taken place, then the CNRP could have used the Senate as a bulwark against the National Assembly, something the Upper House has never really done before,” he told The ASEAN Post.

He concluded that these events confirmed that Cambodia is fast becoming a single-party state. The remainder smaller opposition parties are disenfranchised from the broader political scene and many other minor parties do seem to tow the CPP line.

He pointed out that no politician from FUNCINPEC – a royalist political party which was once the country’s main opposition party but has since forged close ties to the CPP – was elected to the Senate. Hutt had predicted that FUNCINPEC would be given a handful of seats to be kept happy. Instead, two of the party’s members were appointed to the Senate by the King. According to the Cambodian constitution, four seats in the Senate are by appointment – two by the King and another two by the Cambodian National Assembly.

Future of Cambodian opposition

Next on Cambodia’s political almanac is general elections – slated to take place in July. With no cohesive opposition to take on the CPP, it is very likely that Hun Sen will breeze through the elections as he did with this one.

Sebastian Strangio, author of Hun Sen’s Cambodia told The ASEAN Post that he remained doubtful that the Cambodian opposition could rebound after their dissolution in 2017.

“The Cambodian government is unlikely to permit the emergence of any opposition grouping that poses a potential threat to its power. Barring some kind of internal upheaval, or other ‘black swan’ event, Cambodia seems poised for a long spell of Chinese-backed authoritarian rule,” he said in an email reply.

Sophal Ear, who is also a policy analyst iterated most poignantly when asked of his opinion on the future of Cambodia’s opposition.

“I remain pessimistic; there’s no light at the end of this tunnel. They say it’s darkest before the dawn. Of course, it’s also darkest just before it goes completely pitch black,” he said.