Across Asia, demographic trends are indicating a growing ageing population with the 65 and above age category projected to more than double, reaching close to 2.5 times the current figures by 2050. Similar patterns can be discerned in Southeast Asia.

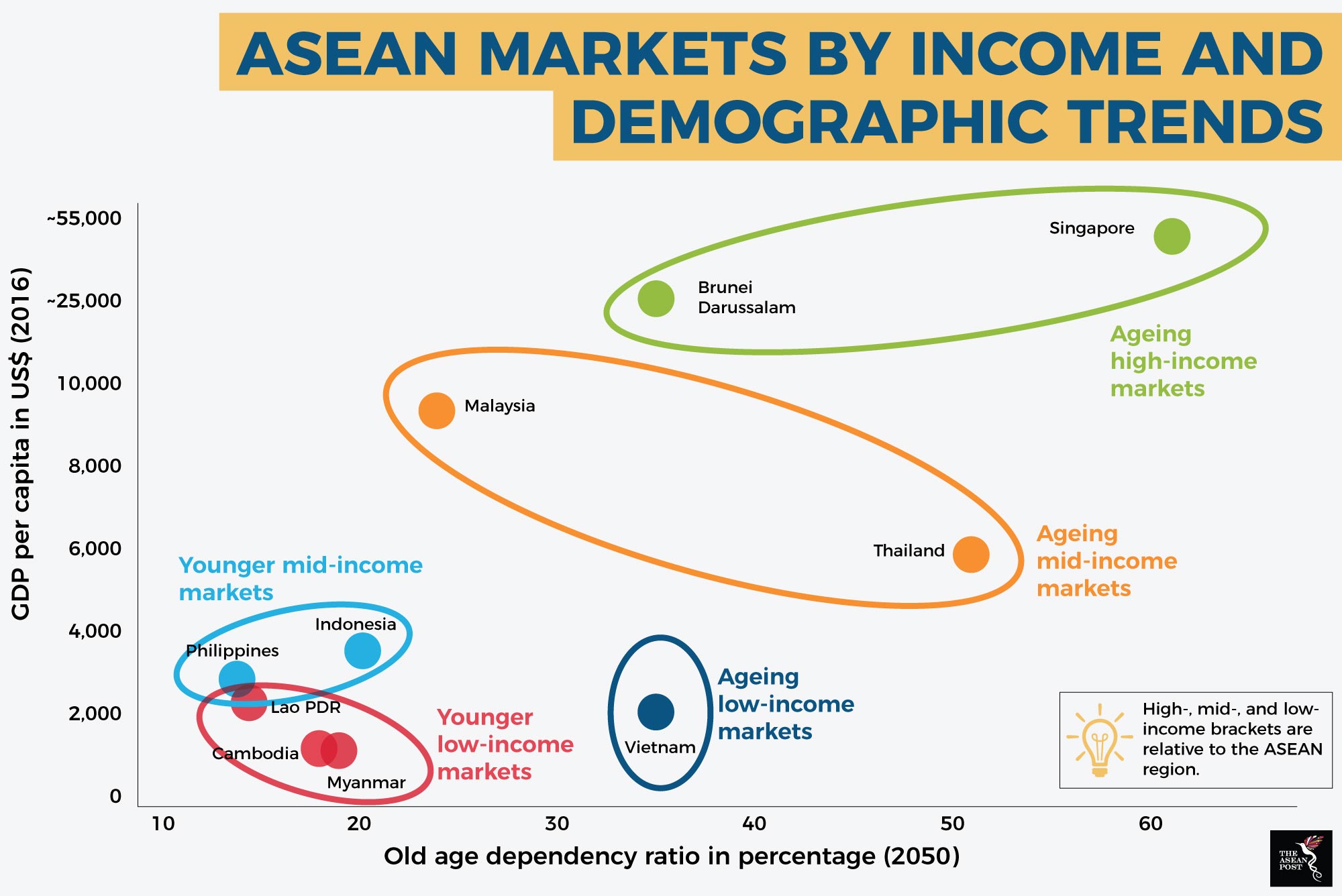

The ageing markets within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) can be divided into three separate categories – high-income, mid-income and low-income ageing markets. According to a recent report, Singapore and Thailand are the fastest ageing markets in the region. Other countries like Malaysia, Vietnam and Brunei are all ageing albeit at a more moderate pace.

Ageing high income markets

Singapore and Brunei fall under the ageing high income markets bracket which have limited demographic wiggle room to maximise growth potential. Singapore is projected to reach a high old age dependency ratio of over 25 percent by 2025 with Brunei reaching such levels by 2040. The old age dependency ratio is a measure of the number of elderly people as a share of those of working age.

However, both markets have the highest gross domestic product (GDP) per capita levels in the region – upwards of US$25,000 as of 2016 – which will help cushion their respective government’s welfare burdens. Nevertheless, the fiscal strain of an ageing population will soon have an effect there as the working age population decreases, leading to a reduction in the size of the labour force needed to drive economic growth.

Policy intervention is critical to stymie the effects of an ageing society on economic performance. Short-term steps include improving inward migration of a younger cohort of taxpayers to city centres and business districts which have a higher rate of economic activity. Longer term reforms will affect the structural make-up of the labour force, for example, increasing the participation of women in the labour force.

Ageing mid-income markets

Malaysia and Thailand fall within the ageing mid-income markets category and also suffer from a limited demographic window to maximise economic growth. Economically, both these markets are characterised as being the more mature emerging economies of Southeast Asia with moderate gross domestic product (GDP) per capita levels of between US$5,000 and US$10,000 as of 2016. Thailand is expected to reach an old age dependency ratio of above 25 percent by 2030 – enjoying only a slightly longer time frame for intervention than Singapore. On the other hand, Malaysia has more leverage given that it would only reach such ratio levels by 2050.

The impact of an aging population on these two economies are likely to weaken the prospects of an economic boost in the longer term. Coupled with strong increases in wage levels, there is an urgent need to improve worker productivity in order to balance out growing labour costs while still remaining competitive. Thailand and Malaysia have some of the highest minimum wages among ASEAN member states. Moreover, growing protectionist sentiments may pose additional challenges for these trade-reliant markets.

Source: Various sources

Amid a disappearing labour cost advantage, Thailand and Malaysia should adopt the Chinese model of implementing structural shifts towards higher value manufacturing and leave lower-value production to ASEAN’s frontier markets. Accordingly, the future workforce must be trained in the skills required for such higher value-add jobs which will help boost labour productivity levels. As such, both governments there have already begun investing heavily in technology and education to develop the necessary skills required.

Ageing low-income markets

Vietnam stands out as the only ASEAN member country within this market category with higher socioeconomic growth pressures linked to population ageing at lower income levels. Despite economic reforms which have uplifted many from poverty, it still has one of the lowest GDP per capita levels in the region. Moreover, the country is ageing at a steady pace and is slated to reach the 25 percent old age dependency ratio by 2040.

While short-term projections may paint a rosy outlook for its economy, the issue of an ageing population will affect Vietnam in the longer term. “Elderly poverty” would deal the government there a blow in two areas – namely human security and economic productivity – leading to increased welfare expenditure. This is a troubling outlook for a country which already has higher debt levels than other emerging markets around the world. Furthermore, Vietnam’s economy is heavily exposed to extra-ASEAN trade which could be jeopardised given the recent trend of economic protectionism.

Policy reforms should focus on shifting from labour intensive to higher value-add production in the manufacturing sector. Vietnam continues to enjoy positive foreign direct investment (FDI) in this sector and its government should enact more favourable policies which would further drive investment in manufacturing. Besides that, Vietnam should also improve its limited foreign reserves which are necessary to safeguard against short-term risks from capital outflow and debt repayment.

Regional integration

A broadly applicable remedy for an ageing regional population is to improve linkages between ASEAN member countries. Governments in the region must take adequate steps to remove barriers to trade and investment and boost intra-ASEAN trade and investment.

Moreover, advanced economies like Singapore and Brunei should take the lead in developing regional agendas for the reduction of non-tariff measures. This could lead to the building of stronger regional value chains in the future and increased cross-border worker mobility. In that way, ASEAN countries with an ageing population can benefit from other member states which have younger and more agile workforces.

When push comes to shove, no country is an island and the regional domino effect of an ageing population could harm the region’s prosperous economic future if it is not dealt with swiftly. There isn’t a one size fits all approach to handling this issue. Where the effects of national policies end, regional initiatives must pick up the slack.