The concept of centrality has seen a resurgence in use during the past few days, featuring prominently in the speeches and comments made during the recently concluded Shangri-La Dialogue (SLD). The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) defence ministers probably used it during discussions relating to the great power tussle between the United States (US) and China.

The landscape of Southeast Asian geopolitics has taken some interesting turns of late, but the crux of the matter has all but changed. Increasingly, Chinese assertiveness in the region – especially vis-à-vis the South China Sea – has not been taken too kindly by the US.

US Secretary of Defense, James Mattis slammed Beijing for continuing to militarise maritime features in the disputed waters and warned of “consequences” if Beijing continued its actions. Chinese Lieutenant General He Lei then issued a fiery retort, stating that Beijing’s actions were “for the sake of defending ourselves” and that China will not hesitate to take “firm measures” on countries encroaching what it considers to be its territorial waters.

According to Thomas Daniel, a foreign policy analyst with Malaysia’s Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS), the US will not give up its presence and direct involvement in the region. He added that the US’ track record had shown that its administrations are wary of the consequences of a US retreat from such strategic spaces which could be quickly occupied by other actors.

“The rhetoric coming from the US at the SLD also indicates that it will more aggressively work to defend its interests in the Asia Pacific. Nevertheless, there is also a realisation that the US cannot, and should not, do this alone,” he said in an email reply to The ASEAN Post. “Working together with other like-minded countries is an important part of the approach to the Asia Pacific – or rather the “Indo-Pacific” as they like to call it.”

The term, has gained significant currency since it was articulated by Trump during his visit to the region last November. A “free and open Indo-Pacific” has been the frequent buzz-phrase of this administration and is representative of US strategy in Asia as opposed to Beijing’s revisionism in the region.

US policy attitude towards China has taken on another layer, with the entry of India into the geostrategic play.

Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi delivered the keynote address at the summit where he attempted to carve out India’s role within the dynamics of the emerging regional security architecture. Known for his populist tough talk back home, his tone was relatively subdued as he cast himself as a global statesman, sticking to India’s long tradition of non-alignment.

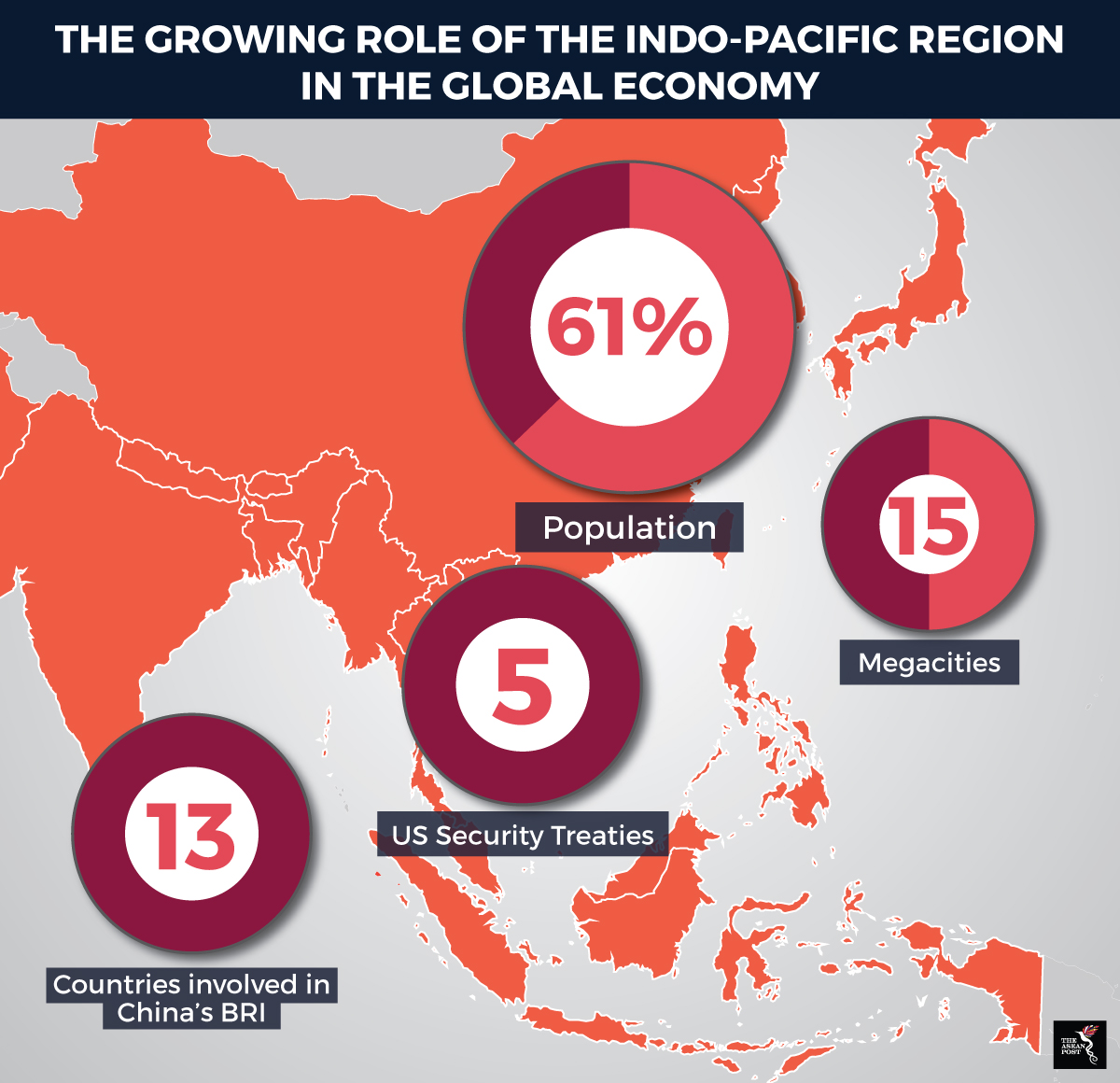

Source: Various sources

As such, he was in a unique position of being able to criticise the increasingly protectionist undertones of the US as well as Beijing’s assertiveness in the South China Sea. In his speech, he placed ASEAN at the heart of the Indo-Pacific agenda and alluded to the association’s leadership capacity amid changing geopolitical realities. Modi also hailed cooperation with China which he believed to be key to greater prosperity in Asia.

Such comments marked a centralist tone and were very much welcomed by ASEAN ministers who prize that attribute above anything else when it comes to great power politicking in the region.

According to Daniel, who’s area of expert analysis includes great power rivalry in Southeast Asia, managing big power relations has always been a major challenge for ASEAN. Now, even more since these major powers – China, India and to an extent, Japan – are increasingly closer to home.

“ASEAN centrality amongst its members is very important – but this itself is in question. The more these major powers decide to influence ASEAN, the more fractured it’ll be. It is a very delicate balance and one whose outcome is very speculative,” he added.

However, the onus lies on India in ensuring Modi puts his money where his mouth is. India and China both have had a resounding influence on Southeast Asia – either by proximity or design.

“India-ASEAN relations, though longstanding, have always been marked by a real gap between intentions and eventual actualisation. This is where China differs,” Daniel explained. “It has a much better track record of not just discussing avenues of cooperation but actually delivering on them – especially in terms of development – a major issue to most developing Southeast Asian countries.”

“China merely needs to ensure that it continues to deliver on this front. India on the other hand, is playing catch-up,” he further remarked.

The recognition given to ASEAN by the likes of the US, China and India will only continue so long as the cherished principle of centrality is upheld. Ultimately, the pursuit of great power could come at a cost for the smaller actor here. Hence, ASEAN needs to stay on it toes as geopolitical realities unfold in the region.