The World Bank estimates the global population to reach 8.5 billion by 2030 with two-thirds of this number living in cities. From that, an estimated 90 million people will move to cities in the ASEAN region, as reported in the 2018 ASEAN Annual Report.

This means that urban dwellers would reflect 45 percent ASEAN’s population where millions of people, especially those living in vulnerable places along river banks, canals and hill sides, will be exposed to the harmful effects of environmental damage. This vulnerable portion of the ASEAN population is expected to increase by 50 percent in the region’s major cities.

When disasters hit, it is always the poor who are most affected, as they are more exposed to environmental hazards and take longer to bounce back from a crisis. Cities are a melting pot of inequalities and climate risk will only exacerbate these inequalities.

Indonesia’s urban population is estimated to account for more than 50 percent of its total population and is projected to increase 65 percent by 2025. The fast-sinking capital city, Jakarta will be 95 percent submerged by then. Relocation of the country’s capital city to the central island of Borneo is expected to lift the burden on Jakarta, and perhaps slow down its imminent doom.

Hundreds of cities and communities are struggling with the impact of environmental crisis as well human threats – including conflicts, failures in governance and economic stress.

Although scientists had made accurate predictions about climate change as early as 1982, millions of dollars have been spent since on misinformation campaigns to sow seeds of doubt in the minds of the general public. Doubt is harmful as it often leads to inaction. And human inaction has led to our current predicament.

What is urban resilience

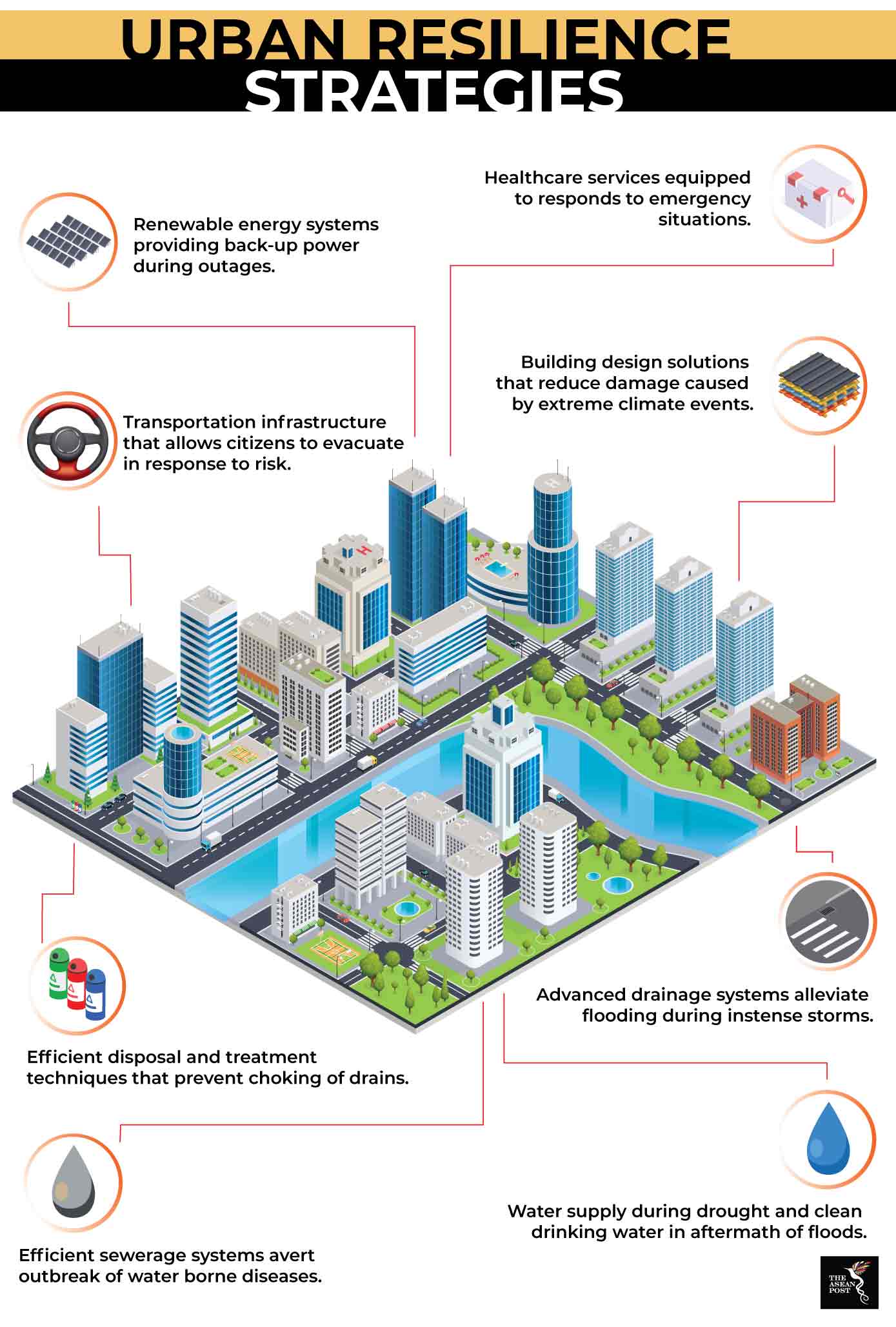

Urban resiliency means the strengthening of city systems to reduce risks posed by climate crisis with specialised tools such as building capable social agents to anticipate and develop adaptive responses and maintain access to supportive urban infrastructure. Building strong infrastructure also requires strong economic, social and governance systems to support physical and intangible resiliency.

Ahead of the Climate Action Summit 2019, the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General issued workplans for infrastructure and cities to ensure carbon neutrality by 2050, decarbonisation of the transport sector, localised/decentralised finance, resilient and zero-carbon buildings standards and codes and urban climate resilience for the most vulnerable.

Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat speaking at the FutureChina Global Forum held as part of the Ecosperity Conference 2019, said that the “world is facing major challenges in sustainable development.” He continued by suggesting ways to combat climate change through the collaborations of all segments of society; the government, businesses and individuals.

He invited companies to participate with Singapore in research and development efforts (R&D) to “create new knowledge and solutions in areas such as food resilience, water, energy and land management.” Singapore also implemented a carbon tax to reduce carbon emission in an economically efficient way. Heng also added that 2019 is designated as the “Year Towards Zero Waste,” for Singapore.

Climate crisis disasters can undermine decades of growth through a single catastrophic event, and supporting cities to be resilient is imperative in order to absorb the impact of such hazards. Yet, it is also vital to change the way we build and manage our cities.

City smart

For many, there is great promise in new technologies offering effective urban solutions. Armida Salsiah Alisjahbana, a UN Under-Secretary-General and Executive Secretary of the UN’s Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), said that “smart grids and district energy solutions, or real-time traffic management, to waste management and water systems, and smart technologies will enable our future cities to operate more effectively.”

Smart cities, energy systems and transportation solutions, along with changes in technology and citizen participation are offering alternatives to protect cities and the environment as well as reducing their contribution to global warming. An example is the ASEAN Smart Cities Network (ASCN), which is designed to mobilise smart solutions throughout Southeast Asia. Currently there are 26 cities, including Kuala Lumpur and Johor Bahru which are developing visions for their cities through technologies.

A new effort to build sustainable cities is degrowth, that focuses on transforming the city rather than consuming more. Scholars and activists have convincingly argued that degrowth in developed nations will need to be part of a global effort to tackle climate change, and to preserve the conditions to satisfy the basic needs of future generations.

Climate change, global warming or extreme weather – whatever the name you prefer – will have the same negative impact on cities. The downside of not investing in city resiliency is the detrimental effect not only on the environment but on the economy, society and political structure as well. The devastation will be unimaginable. How long before we realise that changing lightbulbs or eating plant-based diets is simply not enough without large-scale systemic change?

Related articles: