In the face of growing economic protectionism, undergirded by a trade tiff between the United States (US) and China, Southeast Asian economies are bracing for the impact from a possible economic fallout. Over the past few months, US President Donald Trump has not minced his words when commenting on the trade deficit between the US and its key trading partners.

The latest blow will be dealt on Friday 12:01 (Eastern Time) when tariffs on US$34 billion worth of Chinese imports are due to go into effect. This represents a small sum compared to the US$450 billion worth of Chinese goods that Trump has in his tariff crosshairs in the event Beijing decides to retaliate.

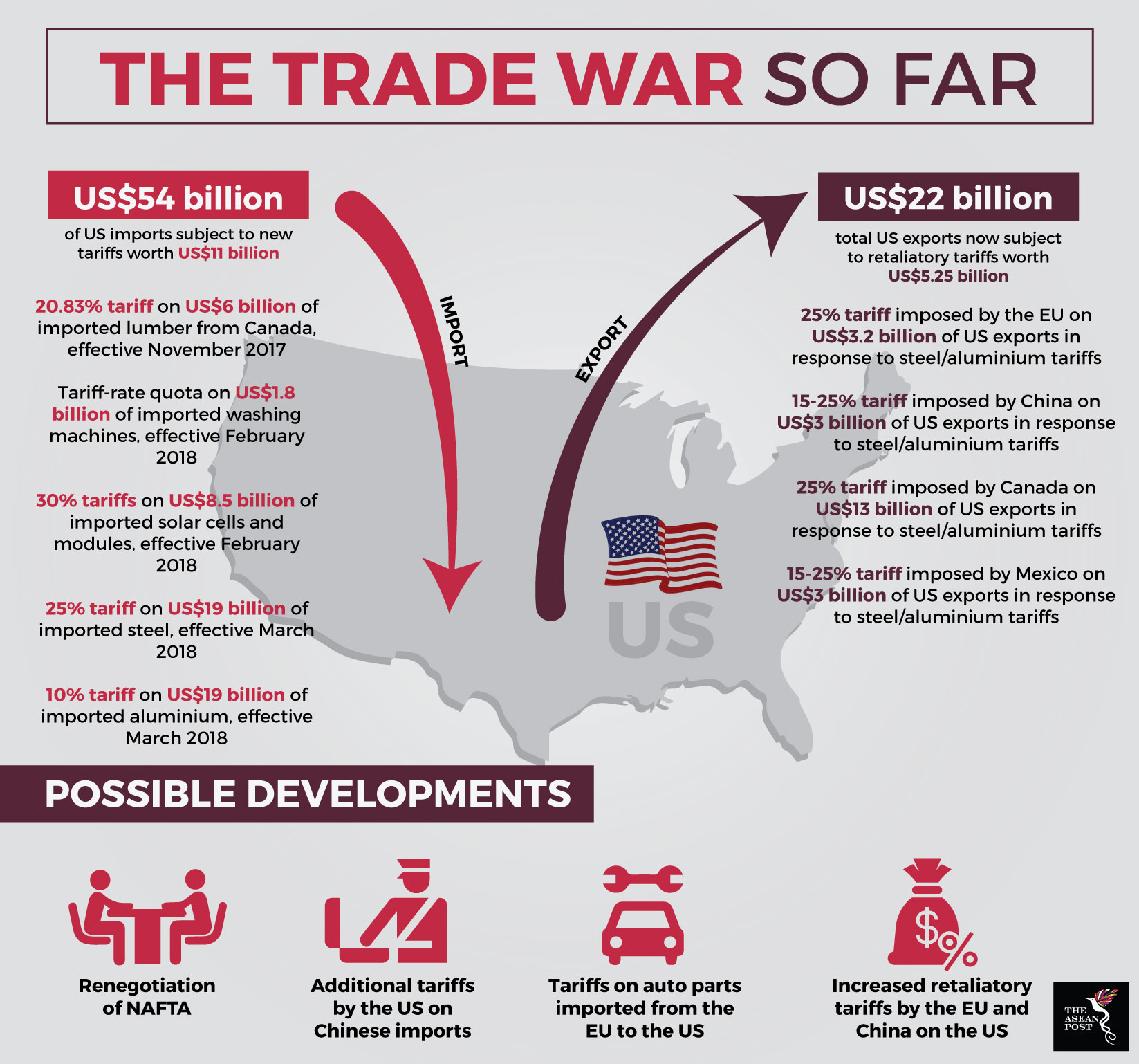

China is expected to respond soon and this, according to Christine Lagarde, head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), would begin a tit-for-tat cycle which would only create “losers on both sides.” The European Union (EU) has also been dragged into this tariff spat with the US, with Trump levying duties on steel and aluminium from the EU with future plans to impose similar duties on European cars.

The economic implications of tit-for-tat tariff measures are global and will especially be felt by Southeast Asian markets that are fairly reliant on China in terms of trade. Countries like Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore would be relatively more affected by US tariffs on Chinese goods as they are intermediaries within the global supply chain.

Previous warnings from China that the interconnected nature of global liberal markets and supply chains would eventually harm US markets have not been heeded by the Trump administration. Nevertheless, China’s apprehensions are accurate. Across Asia there exists a sprawling production network that is heavily integrated with Southeast Asian countries providing intermediate goods to China which is then assembled and exported to predominantly western markets. Because of this characteristically export oriented nature, the spill over effects of a US-China trade war could have drastic implications on Southeast Asian economies.

Source: J.P. Morgan

According to a 2017 report by the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, intermediate goods account for upwards of 50 percent of Southeast Asian exports and imports with China. Even if Beijing decides to reduce its dependence on imported intermediate goods, it must also keep in mind its other economic priority with Southeast Asian countries – investment.

China’s mammoth Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has firmly entrenched its footprint in the region. Its investments in energy, transport and real estate in Southeast Asia accounts for 78 percent of its cumulative investments in the region. This trade-investment relationship is one that China would be hesitant to break and as a result, places downward pressure on its economic growth which would have a domino effect on Southeast Asian economies.

The hardest hit market in the region would be the Philippines with exports to China forming 16.9 percent of its total shipments as part of the value chain. Comparatively, Malaysia and Vietnam export 11.4 percent and 2.2 percent, respectively.

Hence, policymakers throughout the region are shifting focus in an attempt to bolster local markets and negate the impacts of the tariffs. Indonesia, the largest economy in the region is driven mostly by consumption and its Finance Minister, Sri Mulyani Indrawati told Bloomberg recently that Jakarta is looking to “diversify economic growth beyond exports.”

Going forward, it is important for economies in the region to improve domestic demand so as to fuel growth and reduce dependence on exports that have been slapped with tariffs. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates that strong investment and domestic consumption will accelerate growth in the region specifically in markets like the Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand while more industrialisation will boost Vietnam.

Besides that, ASEAN member states must continue to strengthen economic linkages amongst themselves to weather the imminent trade war storm. It would also help if non-tariff barriers and regional trade deals like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) are sorted out swiftly as they could be useful counterweights in a looming trade war.