With the noble goal of pushing a country’s population towards healthier alternatives, the sugar tax is a much-debated topic. While critics deride the policy as ineffective due to consumers’ resistance to change, its supporters hail the tax primarily as a means to curb soaring obesity rates, tooth decay and non-communicable diseases (NCD) such as diabetes, heart attack and cancer.

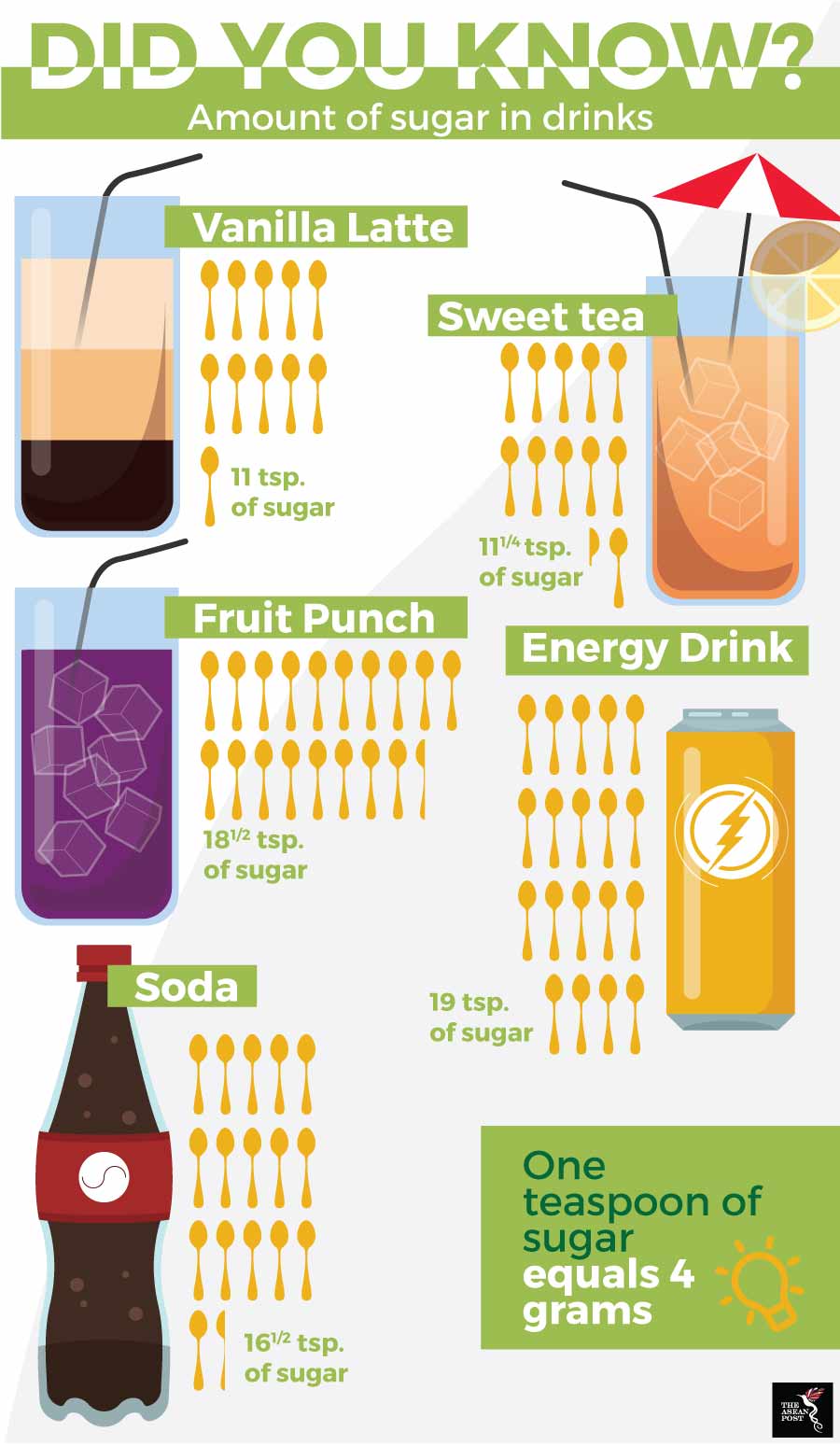

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends adults to limit their daily caloric intake from added sugar to not more than five percent, which equates to about six teaspoons of sugar per day. But with a can of soda containing up to 10 teaspoons and a bottle of juice containing up to six teaspoons of sugar, the lack of awareness by most people about these numbers has led to the rising prevalence of obesity and NCD. One teaspoon of sugar is roughly four grams.

With five countries in ASEAN already rolling out sugar taxes, and others in the bloc considering the move, Malaysia will be the latest country to attempt to put a dent in its citizens’ sweet tooth come 1 April.

Following studies which showed that more than half (51.8 per cent) the Malaysian population in 2017 was either overweight or obese, Malaysia’s Finance Ministry announced a tax of US$0.10 for beverages that contain sugar exceeding five grams (g) per 100 millilitres (ml) and juices that contain more than 12 g per 100 ml.

The healthcare cost of obesity related illnesses is enormous in Malaysia, with estimates ranging from US$1 to US$2.1 billion according to a 2017 study by the Asia Roundtable on Food Innovation for Improved Nutrition. This works out to be about 10 to 19 percent of Malaysia’s total spending on healthcare.

In a report entitled ‘Tackling Obesity in ASEAN’ released by the Economist Intelligence Unit in 2017, it was found that among the factors contributing to Malaysians’ growing waist lines and health problems were rising incomes, shifting lifestyles and lack of awareness about sugary drinks.

Sugar taxes have been implemented across the world and studies from the United Kingdom (UK), Chile and Mexico have shown that in the short term, young consumers were likely to reduce their sugar consumption by up to 80 percent – although older consumers were less prone to change their ways.

Mexico’s example is the most notable; the country witnessed a 6.3 percent reduction in soft drink consumption and a 16.2 percent increase in bottled water purchases after passing a 10 percent tax on all soft drinks in 2013.

Thailand began a phased sugar excise tax in September 2017 which will increase over the next six years, and in Singapore, the Ministry of Health (MOH), the Health Promotion Board (HPB) and relevant stakeholders concluded 10 dialogue sessions on Friday (25 January) and will now study comments from more than 3,000 members of the public before deciding to create laws which address high sugar consumption.

The Philippines’ sugar tax is US$0.11 per litre of drinks sweetened with either sugar or artificial sweeteners and US$0.22 per litre for drinks sweetened specifically with any amount of high fructose corn syrup. Brunei’s tax stands at US$2.95 per 10 litres of drinks with over six grams of sugar per 100 ml. The tax is five to 10 percent in Lao and 20 percent in Cambodia.

Source: Various sources

However, these taxes have only been implemented in the last two years and it is too soon to judge their impact. Clearly Malaysia’s inclusion in the “sugar tax” club is inevitable. The question is will it be effective?

In a country where eating is probably the national past-time, experts predict a mixed response to April’s upcoming sugar tax – which only targets a portion of the country’s problems of diabetes and obesity.

“A tax will save millions of teeth, lower the incidence of obesity and diabetes and improve our financial health by reducing the cost of healthcare besides adding to the treasury’s coffers,” said the Malaysian Dental Association.

But old habits die hard, especially in Malaysia – where it has been reported that one in three consume at least one can of soft drink every day.

“Older individuals and those who already have high-sugar diets for decades are unlikely to change habits and are relatively insensitive to price increases. In the long term, consumers will very likely be desensitised to the price difference, requiring additional tax increases in the future,” said Azrul Mohd Khalib, CEO of Malaysia’s Galen Centre for Health and Social Policy.

With this in mind, there are other initiatives the government can implement to tackle the problems of obesity and NCD which can be rolled out in tandem with the sugar tax.

Stricter marketing regulations – especially to children – have to be studied. Simplified nutrition information on drinks’ packaging – for example, labelling how many teaspoons of sugar a drink contains – and campaigns to highlight the risks of sugary drinks and NCDs as well as the benefits of a healthy lifestyle are also steps which all governments can take.

Taxation alone is not enough to curb countries’ addiction to sugar, and a more holistic approach will be key in encouraging a healthier population.

Related articles:

Governments must stand up for health