Back in March, 2017, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was described by the international media as being broad and comprehensive, involving policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people connections.

Notwithstanding, many foreign analysts claimed that this initiative is Chinese president Xi Jinping’s attempt to gain political leverage over his neighbours, including the fast-growing Southeast Asia region.

Through the BRI, we can see that China aims to build a massive network of infrastructure including roads, railways, harbours, airports, pipelines and even fibre optics across different continents. These infrastructure projects might be demanding for a developing country like Vietnam.

Vietnam’s 2011 - 2020 Socio-Economic Development Strategy highlights the need for structural reforms, environmental sustainability, social equity and the emerging issues of macroeconomic stability such as interest rates and national productivity as mentioned by The World Bank. This can also be defined in three ways; to promote skills development particularly for modern industry and innovation, to improve market institutions and for further infrastructure developments.

Vietnam hanging back

According to an analysis in March 2018 by the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies-Yusof Ishak Institute (ISEAS-YII), there is a huge demand for infrastructure investments in Vietnam and the country stands to benefit from the BRI. Nevertheless, Vietnam’s reaction to the BRI is ambivalent at best because of the complicated political, economic, and strategic relationship between the two countries. A good example of this would be the South China Sea dispute.

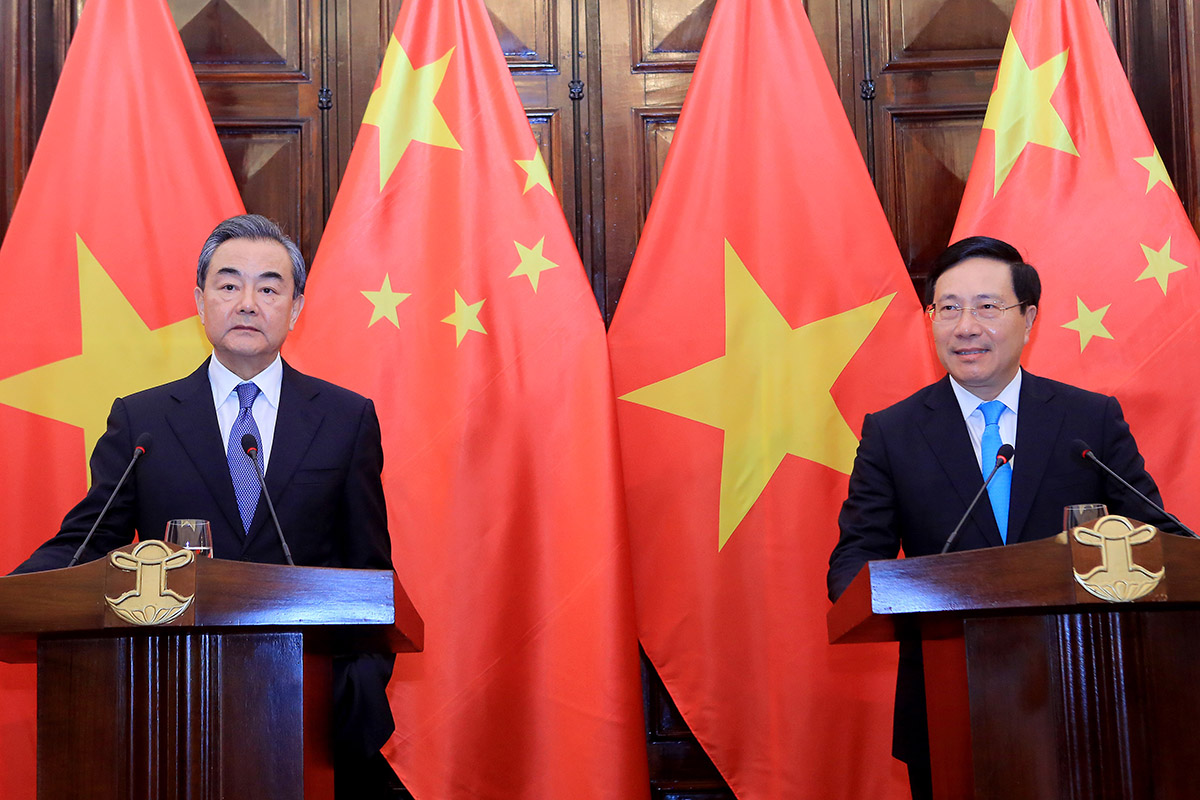

It took two years for Xi Jinping and Nguyen Phu Trong, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam to reach a consensus with regards to the implementation of the BRI in Vietnam. According to Rumi Aoyama in the Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies which was published in March 2017, both nations agreed to establish an "infrastructure cooperation working group" and a "finance and currency cooperation working group”. In addition, it is believed that Vietnam would be one end of the 21st century Maritime Silk Road.

Why is Vietnam agreeing to China’s plan?

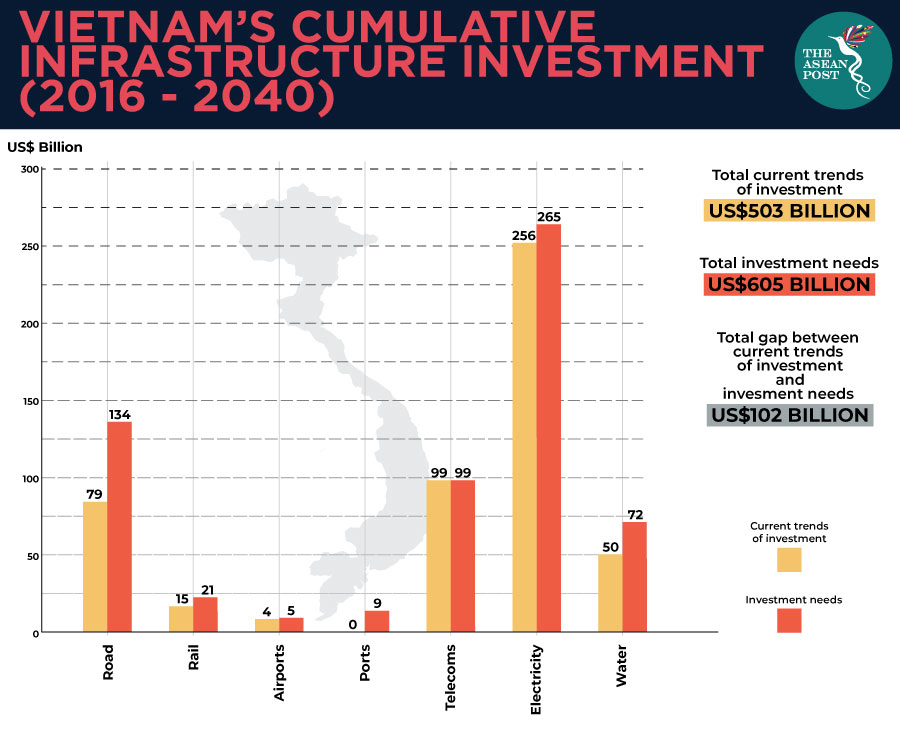

The Global Infrastructure Outlook 2017 by Global Infrastructure Hub, clearly states that Vietnam needs a total of US$605 billion for its investment from 2016 - 2040. However, Vietnam only has US$503 billion and the gap is a staggering US$102 billion.

Therefore, Vietnam will have to seek for proactive measures to cover this gap and the BRI is definitely a crucial source of funding that it can tap into.

Tug of war

The two countries signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in November 2017 promoting the connection between the “Two Corridors, One Belt” (TCOB) framework and the BRI. However, the formation of the TCOB framework which was proposed by China in 2003 was not implemented until the end of 2013 when the BRI was introduced.

As stated by the ISEAS-YII, Vietnam is well aware of the BRI’s implications for the country.

“The signing of the MoU, however, does not guarantee that the BRI will see breakthroughs in Vietnam in the foreseeable future,” stated Le Hong Hiep, a Fellow at the ISEAS-YII.

Le’s statement is valid as Vietnam is keen to maintain control over the TCOB plan. Aside from that, Vietnam does not want the TCOB to be branded as a part of the BRI, at least not publicly.

Although Vietnam might consider the possibility of tapping into China’s BRI as a source of funding, the country is well aware of what happened to Thailand in April 2016. At the time, Thailand dismissed the 2.5 percent interest rate offered by China for the high-speed rail line project because the rate was deemed too high.

Subsequently, Vietnam has another alternative for its funding. The Official Development Assistance (ODA) from Japan that offers services and equipment has more credibility than Chinese funding as stated in a recent analysis by the ISEAS-YII. This has pushed China to work even harder to convince Vietnamese authorities to accept the BRI.

Currently, Vietnam is still awaiting the outcome of the first batch of BRI projects before making any further decisions. Likewise, nations around the region and beyond are looking on to see if there are indeed significant benefits from working with China as it continues to steamroll the BRI.