The world has been taking a beating from environmental abuse by industries, particularly where waste management is concerned. In a traditional economy, mainly dominated by a linear model of take-make-and-dispose, not much consideration is given to the material’s end-of-life. Resources or inputs are harvested from the environment, manufactured into materials, and channelled into the industrial process to make products. Consumers then buy these products, which are soon disposed, either in landfills or in incinerators.

This is particularly true when it comes to the fashion industry, especially due to the new phenomenon of fast fashion, a term used to describe high speed and cost-effective catwalk-to-store delivery of high-fashion trends. The disposable nature of new fashion, alongside a growing disposable income, are key drivers of the doubling of clothing production in the last 15 years. Around the world, the US$1.3 trillion clothing industry employs more than 300 million people along the value chain.

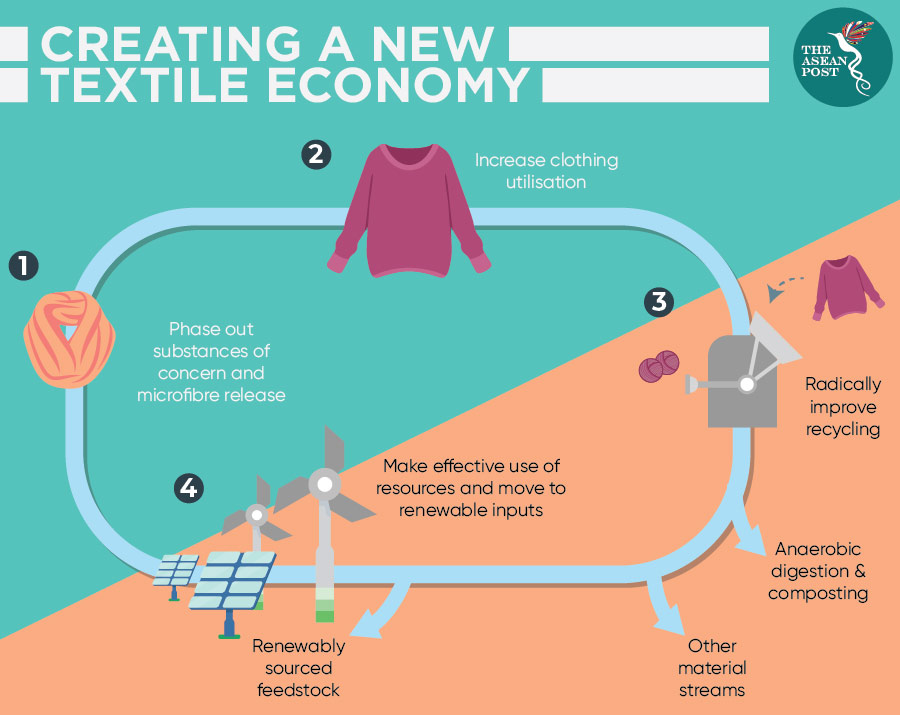

However, the quick turnaround of new style in the fashion industry is fast becoming one of the main drivers of pollution by the industry. A study by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation titled, ‘A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future’ estimates that more than half of fast fashion produced is disposed in under a year. Over the last 15 years, clothing utilisation or the average number of times a garment is worn has decreased by 36 percent. This can be seen in the United States (US), where clothes are only used for a quarter of the global average, and in China, where clothing utilisation has decreased by 70 percent.

There has been a fresh movement from within the fashion industry to counter the fast fashion phenomenon. A study by the Global Fashion Agenda and The Boston Consulting Group on the sustainability of fashion has shown that across the industry globally, progress has been made to improve environmental and social performance, especially from small and medium companies in the mid-price segment. Using a performance scoring mechanism called the ‘Pulse Score’ the study found that, overall, 75 percent of fashion companies surveyed improved their sustainability scores compared to last year.

Southeast Asia’s frontrunner

The textile and clothing industries continue to be the backbone of Cambodia’s export-driven economy, employing 800,000 people around the country, which is 86 percent of all its factory workers, and contributing 40 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP). Cambodia is also home to sustainability champion, Tonlé, one of the frontrunners in processing pre-consumer waste.

Tonlé’s sustainability strategy forms the core of its operations by rerouting and reusing materials which are part of the waste generated by the clothing industry that is usually dumped in landfills or burned. Through this strategy, fashion companies can reduce their massive carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, as well as reduce consumption of water, pesticides in agriculture, and chemicals used to dye fabrics.

“Most of the fabric we source is actually cut waste and quality control failure – so it is very much actual waste and not simply planned waste. We have also pioneered a zero waste design processes to eliminate any waste from our own production and, we are working on some initiatives to help customers deal with the end of life of their garments,” the company’s website stated.

The fashion company has diverted more than 16,000 kilograms (kg) of materials from landfills, reduced 495,000 kg of CO2 from entering the atmosphere – which is equivalent to keeping almost 33,000 cars off the road for a day, reduced consumption of almost 200 million litres of water, and reduced pesticide consumption by almost 12 kg.

The commitment and action by companies like Tonlé goes a long way to not only affecting real contributions, but also driving awareness about sustainable fashion further. The rest of the industry would do well to follow its lead. Active collaboration between various industry players is key to keeping this drive going. The industry needs to start prioritising its long-term impact on the environment and communities where it operates and where its products are consumed.

Related articles: