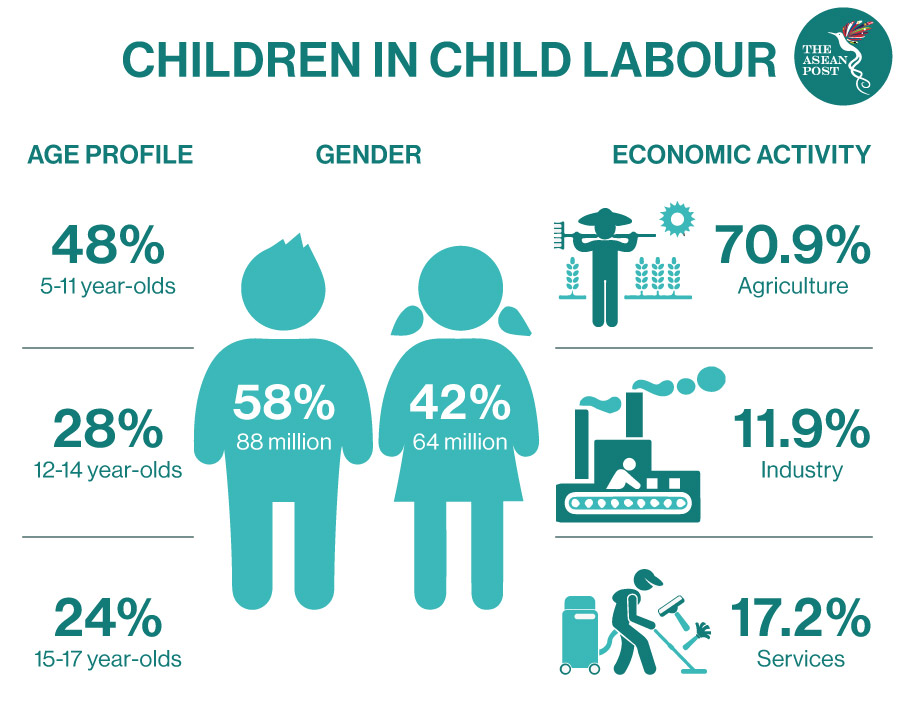

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), about 122 million children aged between five- and 14-years old work for their survival in Asia. Some surveys estimate that there are around 152 to 168 million child labourers across the world. The actual figure is unclear given the variations in the definition of child labour in different countries including variations in age of employability and nature of employment. Other than that, there is also the issue of invisible workers who are not included in research data and surveys.

ASEAN member states have made numerous efforts to improve the lives of millions of children. In 2019, ASEAN joined forces with the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) to launch a joint publication titled ‘Children in ASEAN: 30 Years of the Convention on the Rights of the Child’. The report highlights some action plans in ensuring the rights of every child across all 10 member states. This includes increasing coverage of quality services and continuing to strengthen areas like health, education, child protection and social welfare among others.

Nevertheless, child labour is still a problem in Southeast Asia. It is rampant even in the modern world – despite victims of child labour having decreased in number in many countries over the last few years.

Unfortunately, the ILO and UNICEF recently warned that the current coronavirus outbreak could create the first increase in child labour in more than 20 years. Earlier this month, non-profit organisation Save The Children and UNICEF stated that if urgent action was not taken, the number of impoverished children in low- and middle-income countries could rise by 15 percent to 672 million by the end of 2020.

COVID-19 Crisis

The pandemic has severely affected livelihoods, local industries and the global economy in general. According to the World Bank, the world economy is expected to contract by 5.2 percent this year, the worst recession in 80 years. Millions have already lost their jobs and the current crisis has resulted in increased stress and an economic slump. The World Bank has projected that the depth of the crisis will drive 70 to 100 million people into extreme poverty.

Dang Hoa Nam, director of the Department of Children’s Affairs under the Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs in Vietnam told local media that parents who have lost their jobs and sources of income tend to let their children work to earn some extra cash for their families.

“Poverty is the biggest cause of child labour,” said Nam.

“The pandemic could result in a rise in poverty and therefore an increase in child labour as households use every available means to survive,” explained Lee Hong Loan, chief of the Child Protection Section of UNICEF in Vietnam.

Schools around the world have been closed amid the virus outbreak and classes are now conducted online. A recent report by UNICEF titled ‘COVID-19 And Child Labour: A Time of Crisis, A Time to Act’ states that school closures have affected more than 90 percent of total enrolled learners, or about 1.6 billion students. Some countries such as the Philippines have even announced that schools will remain shut until a COVID-19 vaccine is discovered. Nevertheless, not every child has access to the internet or even computer equipment for distance learning, leaving many poorer students even further behind.

“Children of legal working age may drop out of school and enter the labour market with limited education and skills. Children below the minimum legal age may seek employment in informal and domestic jobs, where they face acute risks of hazardous and exploitative work, including the worst forms of child labour,” stated UNICEF in the report.

The full impact and length of the pandemic, and how different people will fare remains uncertain. But some of the consequences can already be seen happening across the world. Rights groups have urged governments to include everyone in their COVID-19 responses including refugees, people with disabilities and children. UNICEF has also advised authorities to design affordable, gender-sensitive policy responses to help keep children in school and to reduce reliance on child labour.

“Particular attention should be paid to the period shortly after lockdowns when schools reopen. This will be a critical window to prevent children entering paid work and community-level action is needed to ensure that every child returns to school. Children from disadvantaged backgrounds and those who lose a parent deserve special consideration and support,” the UNICEF further stated.

Related Articles: