While at first glance the news that China has asked the Philippines to ban online gambling may seem like just another sign of its growing involvement in the region, a quick scan of regional newspapers soon makes it obvious that the Asian superpower needs all the help it can get to battle its own gambling problem.

Gambling is illegal in China, except in Macau, and gambling businesses are increasingly targeting the mainland China market by opening up shop in Southeast Asia. Eager Chinese punters are now flocking to online gambling sites across ASEAN, and Beijing is worried about capital outflow and money laundering.

On Tuesday, China’s foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang called online gambling “the most dangerous tumour in modern society.”

With accounts linked to online payment platforms, gamblers can play typical casino games like poker, roulette and slot machines in the vast and unregulated expanse that is cyberspace.

Allowing bets as low as 10 yuan (US$1.40), online gambling is especially appealing to lower-income Chinese who may not have the means to go to Macau or other places overseas where they can legally gamble – with the Philippines and Cambodia emerging as hubs to cater to this demand from mainland China.

Seemingly not satisfied with the Philippines’ recent decision to stop issuing new online gambling licenses, Geng said on Tuesday that “we hope the Philippines will go further and ban all online gambling.”

‘I think they like gambling’

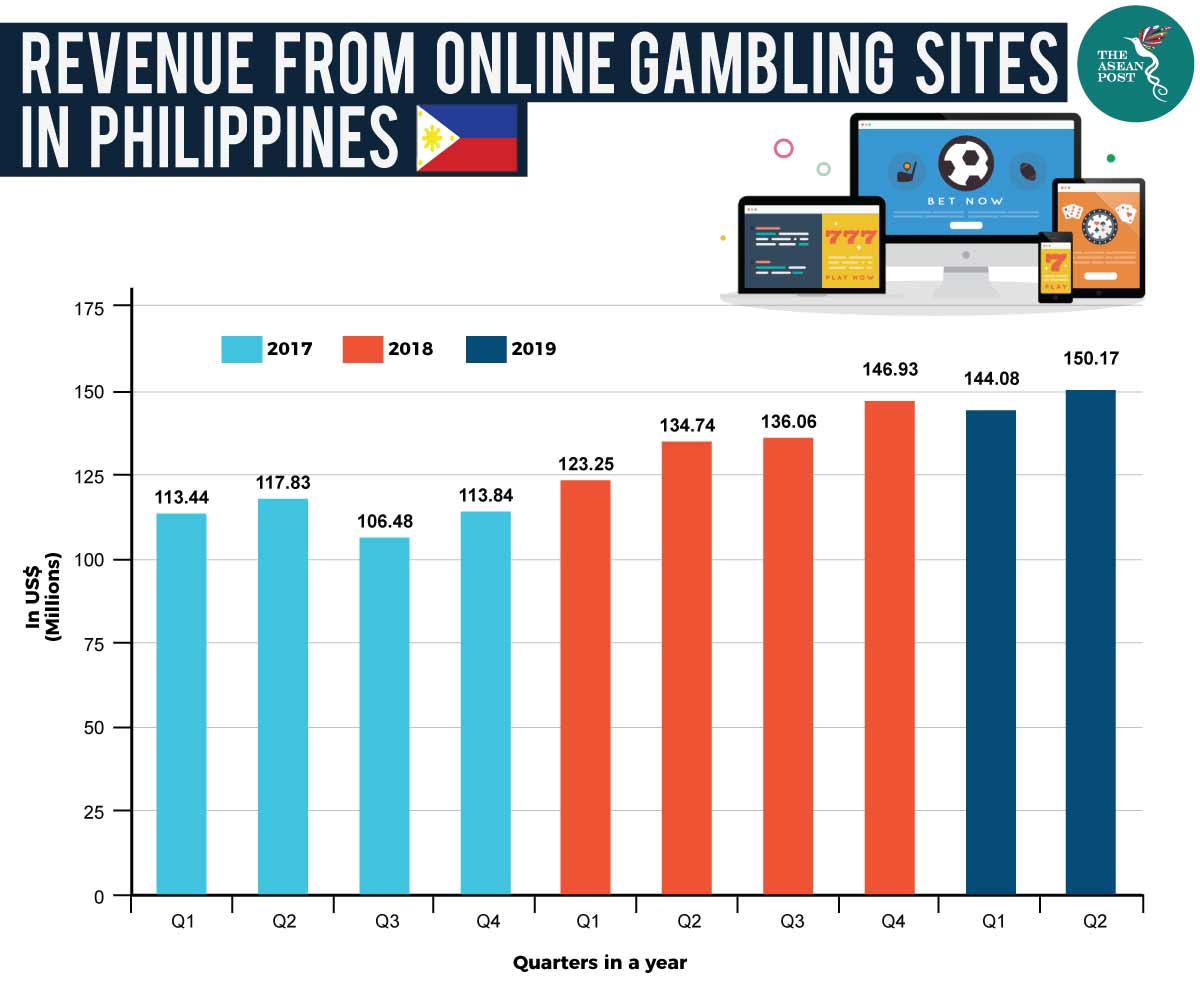

There are 60 licensed Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators (POGOs) in the Philippines and the industry is a lucrative revenue source for the government.

Eager to downplay China’s concerns, the Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation (Pagcor) said that no Chinese firms operate POGOs in the Philippines, POGOs do not stream in countries that have outlawed online gambling, and – interestingly – not all Chinese gamblers are from China.

“I think, in their culture, they like gambling. But it’s not automatic that if the players are Chinese, they are all from China. The players are mostly Chinese, but we are not sure if in fact, they are all from China,” Victor Padilla, senior manager of Pagcor’s policy and offshore gaming licensing division told Philippines media on Friday.

The question of whether these gamblers are from China or not has not stopped the rest of ASEAN from clamping down hard on online gambling.

Headache across ASEAN

Last Sunday, Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen announced the country would ban online gambling by next August as it was used by foreign criminals “to cheat and extort money from victims, domestic and abroad, which affect the security, public order and social order.”

Cambodia relies heavily on China for aid and investment, with the transformation of its fishing town of Sihanoukville into a hub of hotels and casinos regularly cited as an example of Chinese development in the country.

In July, Vietnamese police detained more than 380 Chinese nationals for allegedly running an illegal gambling operation in Haiphong City, 100 kilometres east of Hanoi. Police claimed the ring – which was operating with over 2,000 smart phones and 530 laptops across more than 100 rooms in a gated-community – had processed transactions worth more than US$435 million.

State-run Vietnam Television said the case was the biggest ever in terms of scale and “the number of foreigners breaking laws on Vietnam’s soil.”

Meanwhile in Malaysia, police arrested 97 Chinese nationals for allegedly working for an online gambling syndicate on Wednesday. Operating from an upscale residential area in Kuala Lumpur, authorities believe the syndicate raked in more than US$17,000 daily and solely targeted mainland China gamblers.

Dangers, cooperation

Although Chinese online gamblers may not be at the top of many people’s list of criminals to watch out for, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) stressed in a recent report that ASEAN’s expanding network of casinos – many of which are lightly or not at all regulated – has emerged as a perfect partner or offshoot industry for organised crime groups that need to launder large volumes of illicit money

Concerns of Chinese being coerced to work in ASEAN casinos have recently surfaced, and China’s embassy in Manila has said that dozens of its citizens have been kidnapped, tortured and physically abused by local employers who confiscated their passports.

With gambling now just a click away, ASEAN should be aware of the threat that this can pose to society – whether it is the Chinese behind the screens or their own citizens.

Apart from family and relationship problems, research from the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation also identified emotional and psychological issues – including depression, violence and suicide – as other potential harms of gambling.

Bankruptcy, crime, homelessness, lost productivity and other work-related costs were other harms included in the study titled ‘The social cost of gambling to Victoria’ published in 2017.

China’s Public Security Minister Zhao Kezhi last month called for strengthening of international cooperation to combat online gambling, promising to clamp down on online payment platforms that facilitate cross-border online gambling and the companies that provide technical support for such platforms.

While China and ASEAN might have their fair share of differences, they will have to be on the same side when battling the scourge of online gambling.

Related articles:

How China changed Sihanoukville