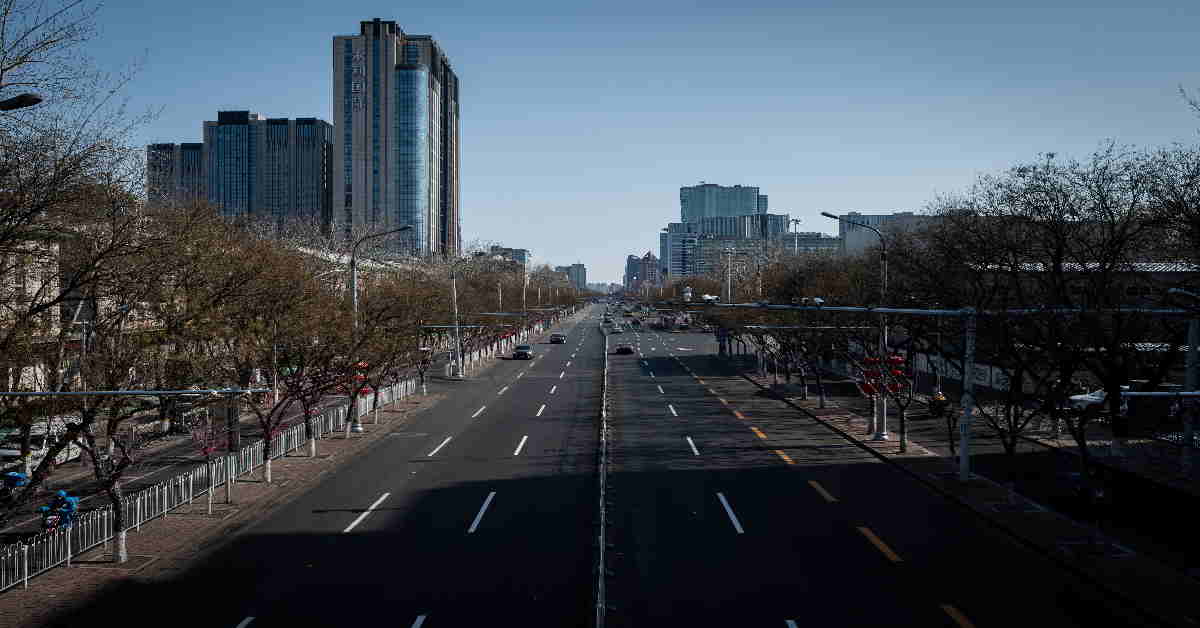

The coronavirus outbreak that began in the Chinese city of Wuhan has spread across the country and beyond its borders, leaving governments at all levels in China scrambling to limit further person-to-person transmission of the virus, now known as COVID-19. Wuhan, with a population of 11 million, is under lockdown. Many provinces have postponed the resumption of work at non-essential enterprises following the Chinese New Year holiday, with residents instead staying indoors in barricaded neighbourhoods. Much inter-city and inter-provincial transportation has been halted. And some local governments have even established illegal checkpoints to prevent vehicles carrying industrial products and materials from entering areas under their jurisdiction that contain factories.

Clearly, the outbreak and the extraordinary official measures to contain it have hit China’s economy hard. No one yet knows when the authorities will manage to overcome the epidemic, and what the eventual cost to the economy will be. But the Chinese people have, once again, shown courage and solidarity in the face of a national emergency. There is no doubt that China will win the battle against COVID-19.

When the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus hit the Chinese economy in the spring of 2003, everyone initially was pessimistic about the outbreak’s likely economic impact. But as soon as the epidemic was contained, the economy rebounded strongly, and ultimately grew by 10 percent that year. China is unlikely to be that lucky this time, given unfavourable domestic and external economic conditions. So, with the deadly coronavirus still on the rampage, the Chinese authorities must prepare for the worst.

Policymakers should respond to the current crisis in three ways. Their first priority must be to rein in the epidemic no matter what the cost. Because markets cannot function properly in emergencies, the state must play the decisive role. Fortunately, China’s administrative machinery is functioning effectively.

At the moment, one of the most serious economic obstacles is the interruption to transport caused by fearful local governments. While recognising local officials’ legitimate concerns about preventing the further spread of the virus, the central government must now intervene to facilitate smooth flows of people and materials, thus minimising supply-chain disruptions.

Second, the government should devise ways to help businesses survive the crisis, focusing in particular on small and medium-size services firms. While being careful not to create undue moral hazard, the government should cut taxes, reduce charges, and compensate hard-hit enterprises generously. It also should consider establishing pandemic insurance funds so that society as a whole can bear businesses’ virus-related losses.

Moreover, commercial banks should strive to ensure that there is no shortage of liquidity, including by rolling over loans to troubled enterprises and allowing them to postpone repayment. In addition, policymakers may need to resort to market-unfriendly measures such as targeted lending and moral suasion to steer the allocation of financial resources, as well as possibly loosening some financial regulations.

Third, the authorities should pursue more expansionary fiscal and monetary policies, even if such measures per se are not aimed at offsetting the negative impacts of supply-side shocks. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) should continue to lower interest rates as much as possible and inject enough liquidity into the money market. Although inflation has risen as a result of supply-chain disruptions and may yet climb further, tightening macroeconomic policy at this point would be counterproductive.

Likewise, although the government is unlikely to launch large-scale infrastructure investment projects before COVID-19 has been contained, the general budget deficit may nonetheless grow, owing to the epidemic-related increase in spending and decrease in tax revenues. In its fight to control the virus’s spread, the government should not worry too much about whether the budget deficit exceeds three percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

The battle against the coronavirus undoubtedly will be very costly, and will reverse some of the Chinese authorities’ recent achievements in reining in financial risks. For now, however, any potential problems related to debt, inflation, or asset bubbles are secondary. Policymakers can worry about them once the situation has calmed down.

Late last year, I sparked a heated debate among Chinese economists by arguing that the country’s policymakers should not allow annual GDP growth to slip below six percent, because expectations of a slowdown are self-fulfilling. In the light of the coronavirus outbreak, I concede that the six percent growth target must be reconsidered. But even if the epidemic lowers growth in 2020 by, say, one percentage point, this probably would not negatively affect people’s expectations, because the slowdown would be the result of an external shock rather than some inherent weakness in the economy.

Chinese policymakers’ most urgent challenge is no longer how to stimulate aggregate demand, but rather how to ensure that the economy functions as normally as possible without compromising the fight against COVID-19. Sooner or later, however, the epidemic will be conquered, and the Chinese economy will return to a normal growth path.

When that happens, the question of whether China needs more expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to achieve an adequate level of growth will return to the agenda. And the rationale for a looser stance will still apply. In fact, to compensate for the losses arising from the COVID-19 outbreak, the Chinese authorities may have to adopt even more expansionary policies than I (and others) had previously suggested.