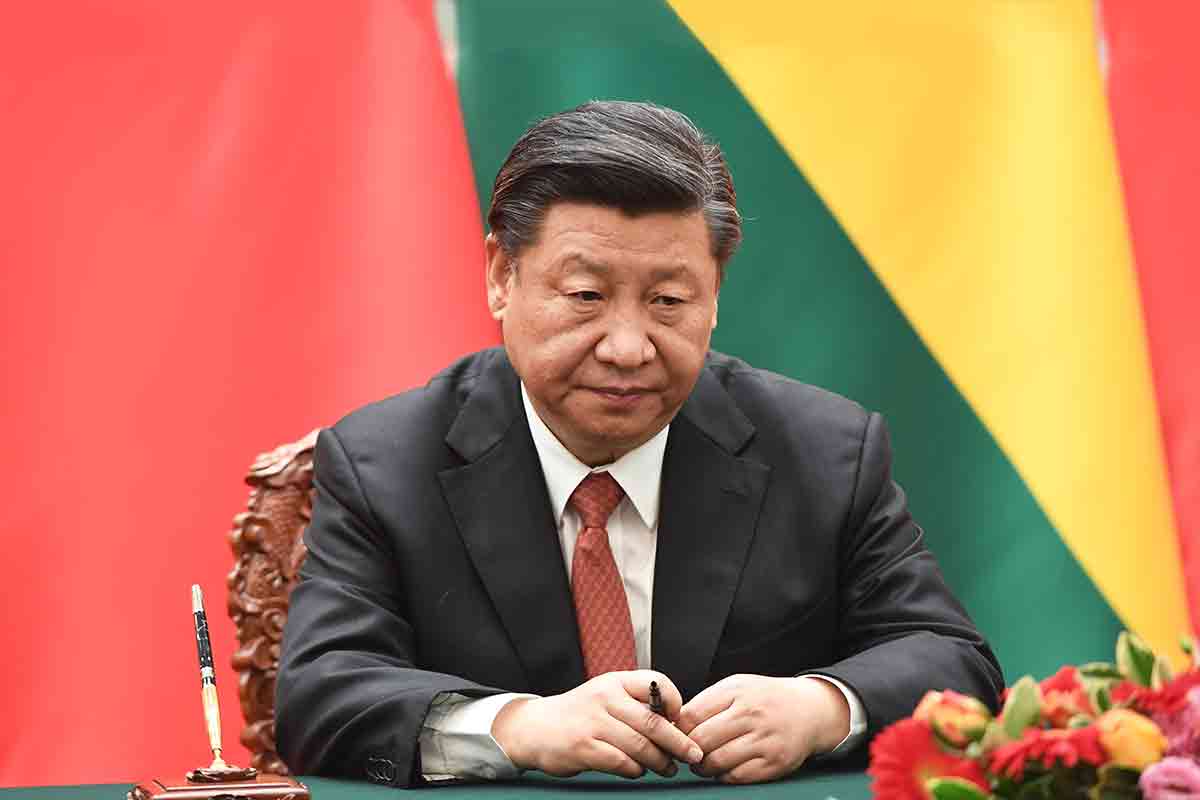

Politics has a nasty habit of surprising us – especially in a country like China, where there is little transparency and a lot of intrigue. Five months ago, President Xi Jinping jolted his countrymen by abolishing the presidential term limit and signalling his intention to serve for life. But the real surprise was to come later.

At the time of Xi’s announcement, the conventional wisdom was that his dominance inside the Chinese party-state was virtually absolute, and thus that his authority could not possibly come under attack. Xi is now facing the worst summer since he came to power in November 2012, characterised by a steady stream of bad news that has left many Chinese – and especially Chinese elites – feeling disappointed, anxious, angry, helpless, and dissatisfied with their increasingly powerful leader.

The latest piece of bad news, which broke late last month, was the discovery by government investigators that a pharmaceutical company had been producing substandard vaccines for diphtheria, tetanus, and whooping cough, and had faked data for its rabies vaccine. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese children nationwide have been given the faulty vaccines.

Of course, China has experienced many similar scandals before – from tainted baby formula to the contamination of the blood-thinning drug heparin – with greedy businessmen and corrupt officials held to account. But Xi has staked considerable political capital on rooting out corruption and strengthening control. The fact that a private company with deep political connections is at the centre of the vaccine scandal is painful evidence that Xi’s top-down anti-corruption drive has not been as effective as claimed. An unintended consequence of Xi’s consolidation of power is that he is accountable for the scandal, at least in the eyes of the Chinese public.

But the backlash against Xi began even before the vaccine revelations. Concerns were rising over the gradual creation of a personality cult. In recent months, Xi’s loyalists have spared no effort in this regard. The desolate village where Xi spent seven years as a farmer during the Cultural Revolution has been branded as a source of “great knowledge” and become a red-hot tourist destination. For some, this is all too reminiscent of the quasi-divine status attributed to Mao Zedong which, during the “Great Leap Forward” and “Cultural Revolution” resulted in millions of deaths and nearly destroyed the Chinese economy.

And, in fact, today’s economic news in China is grim, beginning with a 14 percent decline in stock prices this year. Three summers ago, in the face of sharply falling stock prices, Xi ordered state-owned companies to buy shares to prop up the market. But as soon as the forced purchases stopped, another market decline followed, this time against a background of depleted foreign-exchange reserves. Xi has not repeated that bit of economic illiteracy this time around, but what will come next for China’s stock market remains an open question.

And there is more bad economic news. The renminbi has reached a 13-month low, and while gross domestic product (GDP) growth is ostensibly on track to meet the 6.5 percent target for 2018, the economy is showing signs of weakness. Investment, real-estate sales, and private consumption are all slowing, prompting the government to halt its deleveraging effort and allocate more funds to propping up growth.

The worst economic development, however, is the unfolding trade war with the United States (US). Though its economic impact has yet to be felt, the clash over trade that US President Donald Trump has initiated is likely to be the toughest challenge Xi has faced so far, for reasons that extend far beyond the economy.

For starters, there is Xi’s promotion of the “China Dream,” which entails the country’s revival as a world power. But, as the trade war makes starkly apparent, China remains deeply dependent on US markets and technology. Far from a rejuvenated hegemon poised to reshape the global economy, Xi’s China has been exposed as a giant with feet of clay.

The geostrategic implications are difficult to exaggerate. In the 40 years since Deng Xiaoping began to lead China out of the Maoist dark ages, the country has achieved unprecedented economic growth and development. But that progress would have been impossible – or, at least, much slower – were it not for China’s policy of maintaining a cooperative relationship with the US. Xi has upended that policy during his tenure, not least with his increasingly aggressive actions in the South China Sea.

These developments point to a straightforward conclusion: China is headed in the wrong direction. This is not lost on China’s elites whose frustration is palpable – and rising.

Yet, despite rumours of pushback against his power by retired elderly leaders, Xi is unlikely to be overthrown. He remains solidly in control of the Chinese party-state’s security apparatus and the military. Moreover, he has no rivals with the courage or influence genuinely to challenge his authority, as Deng and other veteran revolutionaries did in 1978, when they pushed out Hua Guofeng, Mao’s hand-picked successor as leader of the Communist Party of China.

Nonetheless, the road ahead for Xi remains treacherous. If he stays his current course, so will China, with each stumble reinforcing negative perceptions of his leadership. Yet changing course could also hurt Xi’s reputation, as it would amount to an admission of flawed judgment – a problem for any leader, but especially for a strongman like Xi. And some of the new policies Xi would have to adopt conflict with his instincts and values.

The risks are real. But Xi probably doesn’t have much choice but to face them. As China’s summer of discontent clearly suggests, he needs a new game plan.

Minxin Pei is a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College and the author of China’s Crony Capitalism.