Both by design and proximity, China has had an immense influence on the Southeast Asian region. The movement of Chinese people to parts of Southeast Asia has helped to facilitate this transference of culture and develop a notion of shared history between these two regions.

The first wave of Chinese emigration took place between the 10th and 15th century where many settled in modern day Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia (Java and Sumatera) and Borneo – marrying natives and assimilating with the local populous.

Soon after the fall of the Ming dynasty in the 17th century, the second wave of emigration began, with many Chinese settling in parts of what is now Cambodia and Peninsular Malaysia.

The third, and most recognisable mass movement of Chinese to Southeast Asia occurred during the British colonial era with a huge influx of Chinese men, attracted by the prospect of work in tin mines. Many of whom were also motivated by the shortage of food due to the Chinese civil war.

The footprint of the movement of Chinese people to this part of the world is evident in the sheer mass of numbers of their diaspora within Southeast Asia. Overseas Chinese populations in Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia alone represents more than one third of the total number of individuals of Chinese descent living outside mainland China.

In today’s globalised world, Chinese nationals are increasingly looking to Southeast Asia for employment opportunities. Economies of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) boast astounding growth rates and are looking to make massive strides in various industries including technology, energy, manufacturing and tourism. Already, Chinese tech giants, Alibaba and Tencent have projected Southeast Asia to be the next frontier of development after mainland China due to its proximity with the latter.

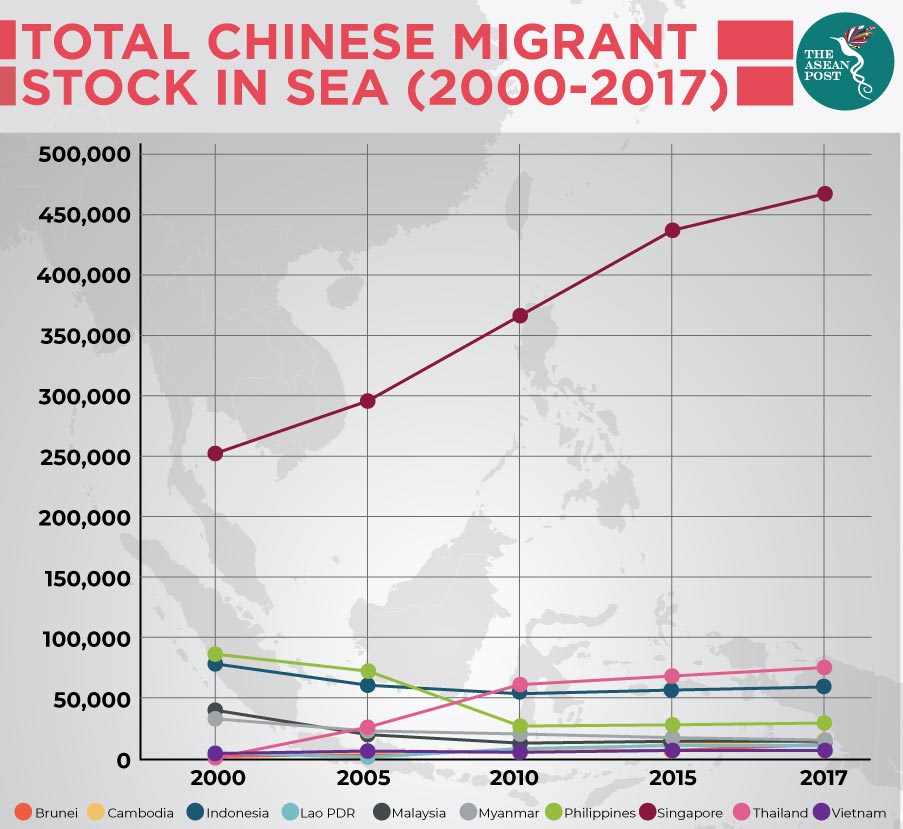

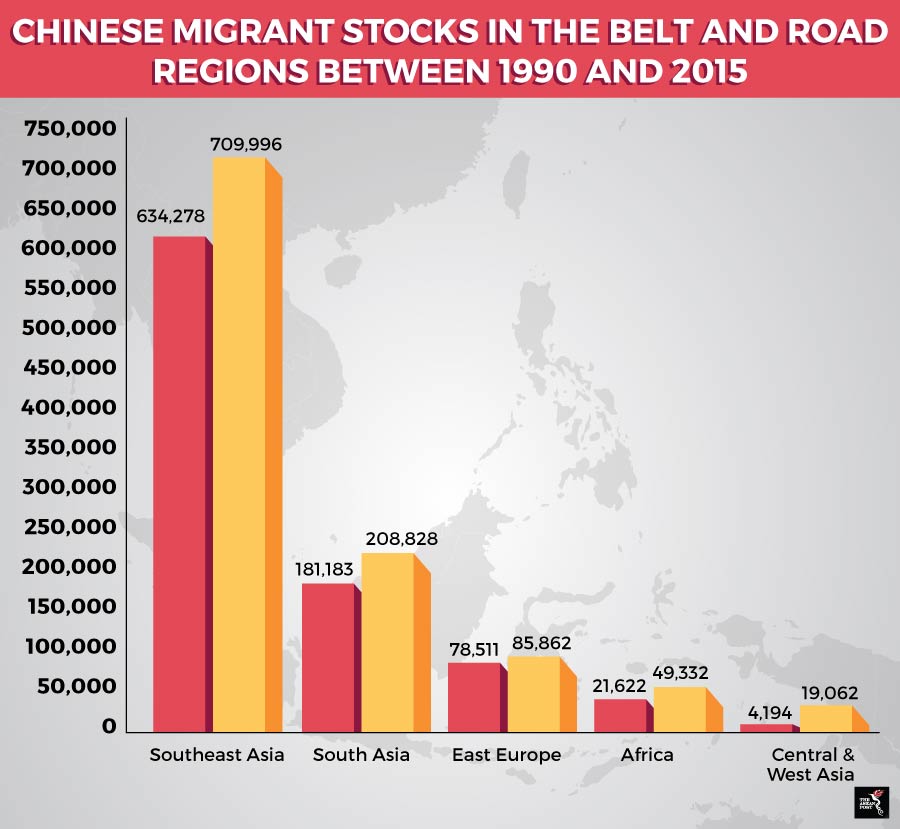

Estimates by the United Nations (UN) Population Division indicate that the number of Chinese migrants has been on a steady rise, driven by their numbers in Southeast Asia. In 2015, the number of Chinese individuals living abroad more than doubled from 4.2 million in 1990 to 9.5 million. Of that number, more than half can be attributed to migration to parts of Asia – primarily Southeast Asia.

Another huge factor prompting a new wave of Chinese emigration to Southeast Asia is the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Along with this flow of lucrative Chinese foreign direct investment into developing billion-dollar infrastructure projects in Brunei, Cambodia, the Philippines and Indonesia – just to name a few – comes the movement of state employees, workers, entrepreneurs and their family members to these countries.

According to Raya Muttarak, Director at the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital, public attitude towards Chinese migrants in BRI countries are dependent on the skill level of these individuals. This is not a far cry from the general pattern of attitudes towards immigrants – where those from lower rungs of the socioeconomic ladder are perceived negatively as opposed to more skilled labour.

Source: Various

In a journal article published last year, she concluded that unlike their predecessors whom were mainly poor and uneducated, this new wave of Chinese migrants are highly educated entrepreneurs. Many of them, seek investment opportunities in the region as a result of China’s overseas economic expansion plans which were set in motion in the 1990s.

Given the prevailing logic that skilled migrants by virtue of earning an income and accumulating capital, contribute substantially to tax revenue in the destination country, public opinion of these skilled Chinese migrants are overwhelmingly positive. However, mobility of Chinese labourers can potentially stir resentment among local low-skilled workers, particularly aimed at those brought in from mainland China as contract labourers to work in infrastructure development projects.

With plans for the BRI showing relatively no signs of slowing down, BRI countries in the region must expect a subsequent rise in Chinese migration to their shores. Judging by recent global experiences with migration, this could possibly open up a Pandora’s Box in terms of how these migrants will be integrated into local culture and societies. Whether the end product of Chinese migration serves to be a boon or bane to Southeast Asian nations may very well depend on this factor.

Related articles: