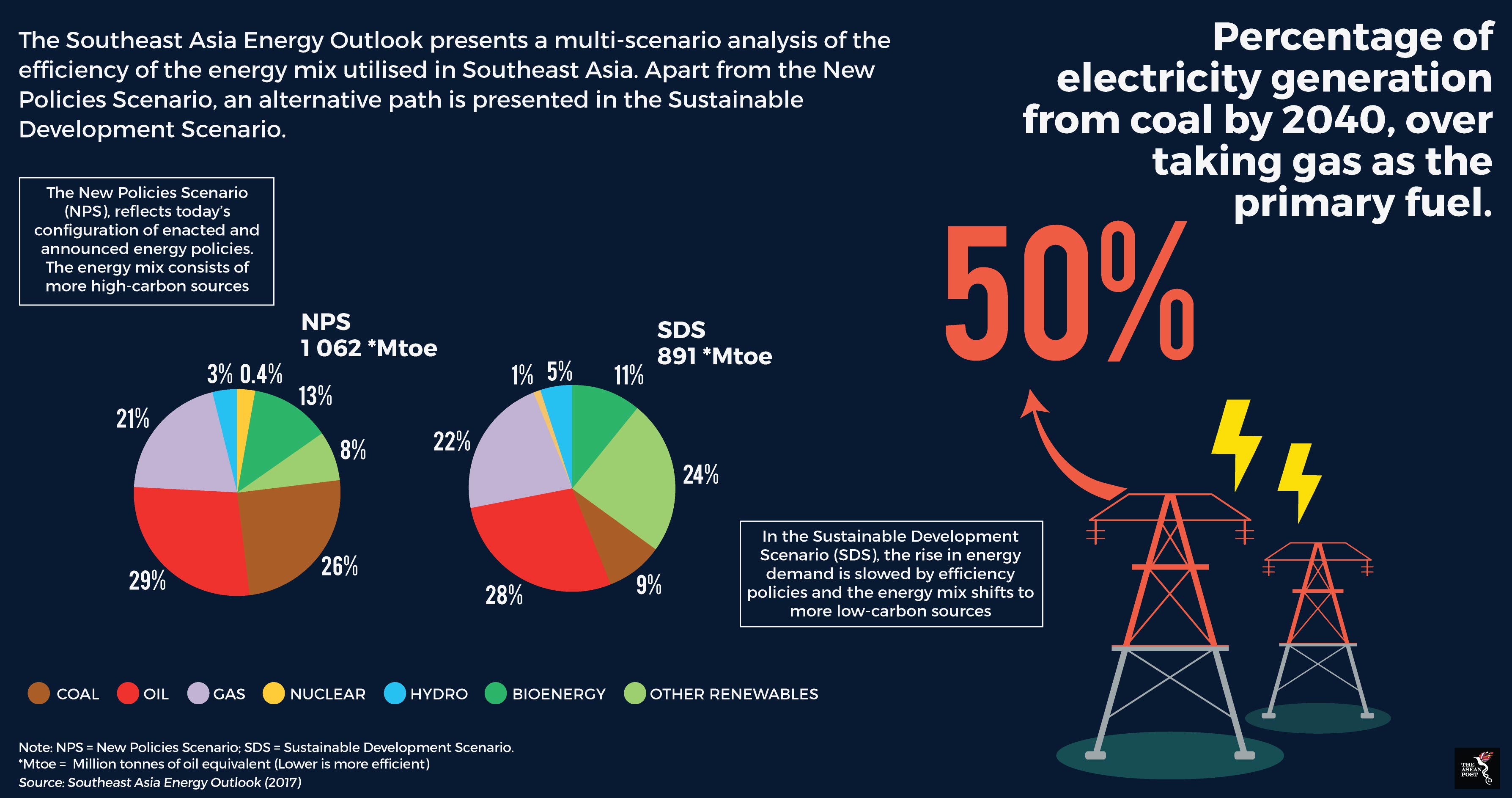

Southeast Asia’s energy demands are expected to increase by 60% in 2040 according to the International Energy Agency, with increasing electricity consumption driving up the demand for coal as well.

Coal will constitute 40% of this growth, to cater to Southeast Asia’s demand for 565GW of electricity by 2040, as reported by the International Energy Agency (IEA) in October 2017.

ASEAN has agreed that in order to ensure sustainable coal use in the region, clean coal technologies to curb the release of harmful carbon dioxide, sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides into the atmosphere must be implemented. This was outlined in the ASEAN Clean Coal Technology (CCT) Handbook for Power Plants by the ASEAN Centre for Energy in December 2017.

The handbook also acknowledges how CCT implementation within the ASEAN region has been slow to materialise.

According to Coral Davenport, a climate change reporter for the New York Times, the term ‘clean coal’ has no clear technical definition.

“Some advocates use it to refer to the burning of coal while using pollution-reducing technology that is already standard in most American coal plants. The term can also refer to technology that traps the planet-warming carbon dioxide pollution emitted by burning coal. It is not widely available commercially,” she explained.

More precisely, clean coal technologies include pollution control technology, high efficiency low emission (HELE) technology, and carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, as outlined by a joint report by the ASEAN Centre for Energy and the World Coal Association in 2017.

According to the 2017 report titled ‘ASEAN’s Energy Equation’, current trends indicate a move towards HELE technology, which is utilised in supercritical (SC) and ultrasupercritical (USC) coal power plants, as opposed to subcritical coal power plants. Shifting from subcritical coal power plants to ultrasupercritical plants would reduce carbon emissions by 1.3 billion tonnes, the report surmised.

Energy economist, Han Phoumin also points out that although USC technology is one of the best options to reduce emissions of nitrogen oxides and sulphur oxides, many developing Asian countries are still unable to afford the high upfront investment costs.

Ultrasupercritical coal plants like Malaysia’s Manjung 4 and Manjung 5 were developed at a cost of approximately RM6 billion each and remain ASEAN’s only completed USC coal power plants to date.

“Lowering these (upfront) costs is necessary and can be done through policy frameworks, such as attractive financial/loan schemes for USC power plants or through strong political institutions that can provide public financing for CCTs to emerging Asia, and international cooperation frameworks to ensure the deployment of CCTs,” said Han Phoumin.

While the need for long-term financing schemes is plain, for now, coal power plant projects in Southeast Asia could be relying on financial backing from foreign governments and banks. For example, according to reporting by the Guardian in 2017, Japan and China are the main financiers of 22 Indonesian-based coal power deals closed between January 2010 and March 2017. It outlined how the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) was part of five deals while the Export-Import Bank of China (Cexim) was involved in seven deals.

“Right now, several key countries supporting the Paris climate change agreement are actively undermining it by trying to expand the polluting coal-power sector in other countries,” commented Julien Vincent, executive director of Australian environmental research group, Market Forces.

Closer to home, Singaporean banks like UBS, DBS Bank and Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation (OCBC) are still funding a total of 21 coal projects worth a cumulative US$2.29 billion since 2012, according to Market Forces research using data from IJGlobal, an infrastructure and energy finance data service. These coal power projects are based mostly in Vietnam and Indonesia.

On the other hand, renewable energy projects may not be as financially viable to investors in Southeast Asia.

According to Allard Nooy, chief executive officer of infrastructure investment firm InfraCo Asia, only an estimated 45% of renewable energy projects in Southeast Asia are bankable, or financially viable. For instance, a draft solar power purchase agreement (PPA) template to Vietnam’s Ministry of Industry & Trade (MOIT) was rejected by the Vietnam Business Forum (VBF) consortium on the grounds of being financially unviable. According to analysis by Baker McKenzie, the draft PPA failed to address key issues such as how currency conversions and inflation would affect its feed-in-tariff (FiT) system and how project defaults, if they occurred, could be resolved.

While renewable energy continues to be deemed unbankable among some quarters in Southeast Asia, the jury remains out as to whether clean coal technology can offer a financially viable option. Which energy source individual nations decide to adopt may ultimately depend on government policy.

Recommended stories: