Dealing with fake news is a balancing act. On the one hand, fake news can be a serious problem as seen in India where fake news has led to numerous lynching incidents. On the other hand, there’s the question of limiting the freedom of the press and hampering its ability to play watchdog.

Member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have gained notoriety for their lack of press freedom over the years. As a result, the most recent results from the 2018 World Press Freedom Index come as no surprise.

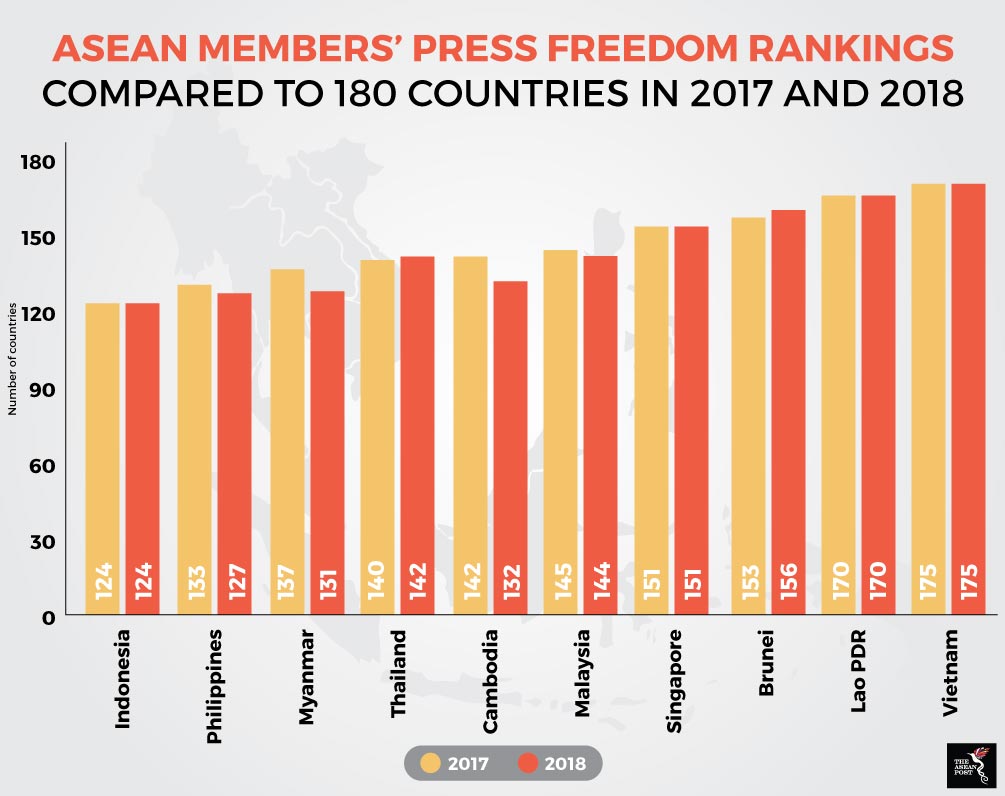

Based on a sample size of 180 countries, Indonesia, Singapore, Lao PDR, and Vietnam have maintained their positions at 124, 151, 170 and 175 respectively, with Vietnam being adjudged to have the least amount of press freedom in ASEAN while Indonesia has the most. Countries that saw improvements were the Philippines which moved up the ladder from 133 to 127, Myanmar from 137 to 131, Cambodia from 142 to 132, and Malaysia from 145 to 144. Countries that actually declined with regards to press freedom were Thailand which moved up from 140 to 142, and Brunei from 153 to 156.

Source: 2018 World Press Freedom Index

ASEAN governments for the most part, have continued prioritising concerns about the spread of false news as opposed to the freedom of the press. In fact, false and misleading news was among the chief topics at the 14th meeting of the ASEAN Ministers Responsible for Information (AMRI) in May. The ministers issued a declaration on a framework to minimise the harmful effects of fake news and agreed that member-countries should work together to improve digital literacy, encourage relevant agencies to develop guidelines for responding to fake news, and to share best practices.

Many ASEAN countries have even gone to the extent of using legislation to stop the spread of fake news. Singapore and the Philippines are in the process of writing their own anti-fake news laws while Thailand has already criminalised the spread of allegedly false information on the internet.

Lao PDR too has an internet law that enforces stricter control over its media. Article 9 of the decree has outlawed the posting and sharing of content that features false and misleading information against the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party and undermines the peace, independence, sovereignty, unity, and prosperity of Lao PDR, as well as information that encourages citizens to become involved in terrorism, murder, and social disorder amongst others.

Malaysia, however, seems to be taking a more proactive role in improving its score on the World Press Freedom Index. On 17 August, the Malaysian lower house or Dewan Rakyat, repealed its Anti-Fake News Law (AFNL). The house voted to repeal the law after a three-hour debate.

ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) Board Member Teddy Baguilat commended the move, saying it showed that the Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan)-led government there was serious about repealing controversial laws which had been passed during the previous government’s rule.

“It also sends a signal to the wider region that positive human rights change is within reach. This is a law that was clearly designed to silence criticism of the authorities and to quell public debate – it should never have been allowed to pass in the first place,” he said.

Fake news is no joke

It would be a mistake, however, to assume that fake news is not a serious problem and that the term is little more than a political tool. Apart from cases of lynching in India, fake news has divided Indonesia ever since the Jakarta elections in April where governor candidate Basuki Purnama, better known as Ahok, was the victim of thousands of allegedly false reports including some that claimed he insulted the Quran.

Several ASEAN member states already have initiatives in place to combat false news. A civic group in Indonesia called The Anti-Fake News Society of Indonesia (Masyarakat Anti Fitnah Indonesia) has set up a Facebook page where people can report and discuss suspected false information. The group consists of six full-time fact-checkers and a search engine listing legitimate news sites. Malaysia also has the government-run sebenarnya.my. If ASEAN is indeed serious about balancing freedom of the press and stopping fake news in its tracks then perhaps fact-checking initiatives like these are the way forward and not legislation.