The truth is a bitter pill to swallow, but it must be admitted nevertheless. North Korea is now a nuclear power.

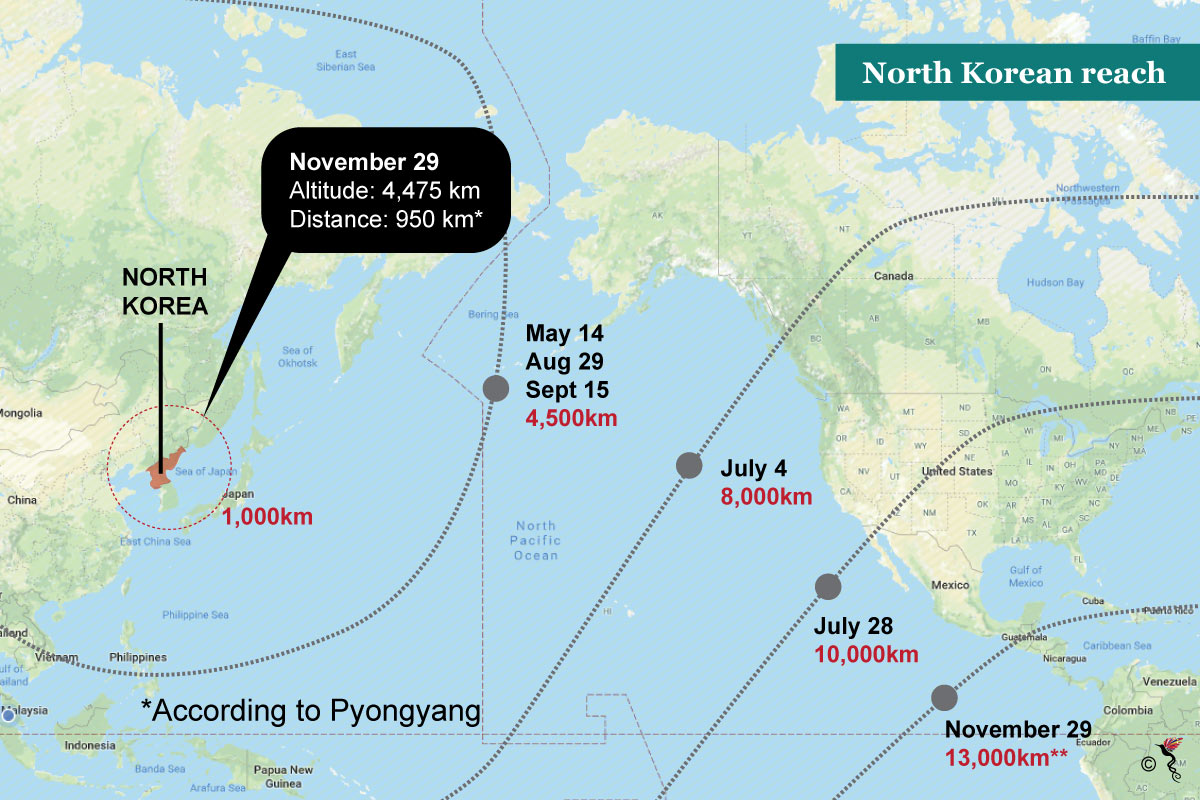

The recent missile test has demonstrated that Pyongyang is capable of launching an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) that could reach the continental United States – it is now a question of if the regime is able to mount a nuclear warhead to that or any other ICBM.

If that happens, we will likely see retaliatory measures resulting in an all-out thermonuclear war.

However, the North, however belligerent it may be, is still a rational actor when it comes to international relations. Kim Jong-Un’s actions have so far demonstrated – despite the buffoonery of his war of words with US President Donald Trump – that besides being a symbol of North Korean propaganda, his nuclear program also serves as a security guarantee and deterrent from foreign attacks.

Reach of North Korea’s missiles (Source: AFP).

“The leadership of North Korea is very concerned about regime survival. They would do everything to improve their bargaining power vis-à-vis the US. Once they have enough self-confidence that the US will not attack in a pre-emptive strike to demolish their nuclear weapon facilities, then they will most likely call for dialogue and negotiations,” said Termsak Chalermpalanupap, Fellow at the Regional Strategic and Political Studies of the ISEAS – Yusuf Ishak Institute in an email response to The ASEAN Post.

Can ASEAN manage the talking table?

The failure of the Six Party Talks – consisting of China, North Korea, the US, Russia, South Korea – has proven that without a proper mediator, the totalitarian regime will continue to stonewall dialogues till kingdom come, resulting in no palpable resolution.

Enter, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) with its colourful tools for dialogue and conflict resolution, steeped in the non-confrontation and consensus building values of the ASEAN Way. The list of acronyms associated with ASEAN’s tools for dialogue – the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), East Asia Summit (EAS) and ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting-Plus (ADMM-Plus) – are aplenty.

But can the association function as a dispute manager for this conflict?

According to Analyst at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS), Thomas Benjamin Daniel, ASEAN can mediate the crisis but only to a certain extent.

“There are several variables here. First, there is the question of North Korea’s preparedness to change the terms and preconditions before any negotiation starts. This currently appears unlikely as Pyongyang has consistently demanded direct negotiations with the US without preconditions – something Washington is unlikely to agree too. Second, ASEAN can only play a role if it is allowed to do so by the other key stakeholders in the Korean Peninsula dispute – the US, South Korea, Japan and most importantly, China.,” he said in an email response.

Nevertheless, he also offered a sobering reminder that, “ASEAN can continue to offer to mediate but better coordination amongst the various ASEAN stakeholders themselves is needed.”

It is this disunity amongst ASEAN member states that often comes in the way of the organisation’s actions. While countries like Malaysia and Singapore have been quick to follow through with sanctions led by Washington, the association is long overdue in converting its rhetoric into action.

Associate Research Fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Henrick Tsjeng believes that a united response involving palpable action will be severely constrained by member states that are unwilling to fully abandon relations with North Korea, as well as ASEAN’s longstanding principle of non-interference.

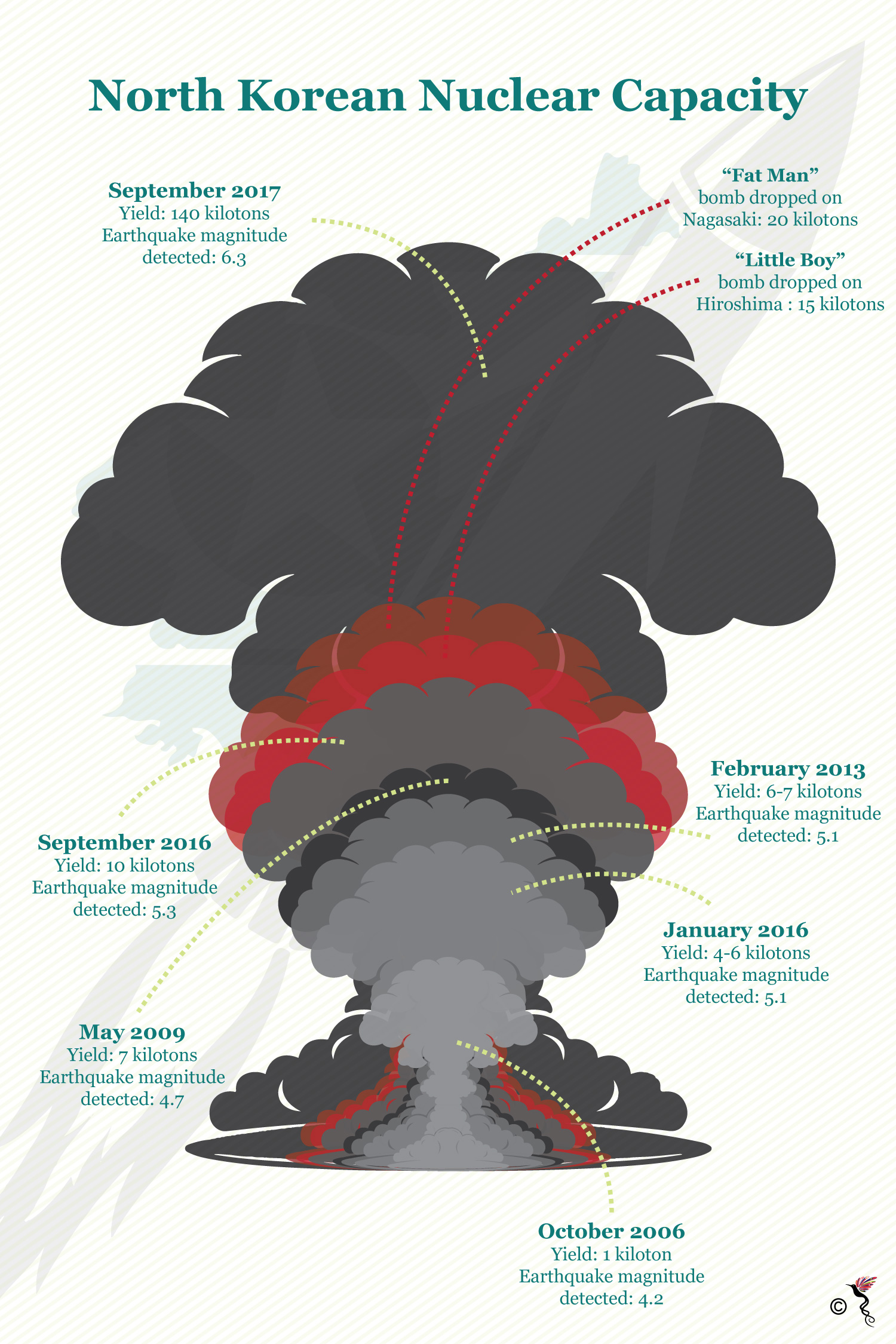

North Korean nuclear tests in comparison to the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

“ASEAN is hardly in a position to have a fairly unified response that entails concrete action, let alone mediate the crisis. Furthermore, any such mediation efforts would be made even more complicated by the likely involvement of both the US and China,” he told The ASEAN Post in an email response.

Rhetoric to action

After celebrating its 50th anniversary, it is high time for the association to play a greater role in mediating the situation developing in the Korean Peninsula as it can spill-over and affect the ASEAN region as well.

South Korean President, Moon Jae-in recently launched the New Southern Policy “to dramatically improve cooperative ties with ASEAN.” In his speech, commemorating the initiative, he expressed hope that both South Korea and ASEAN can strengthen defence cooperation to – among others – “jointly respond to North Korea’s nuclear and missile provocations.”

Senior Lecturer in the Strategic Studies and International Relations Program at the National University of Malaysia, Hoo Chiew-Ping holds that the ARF and ADMM-Plus can be better empowered to facilitate dialogue between relevant actors of the conflict.

“The ARF can be extended to hold a peace process on the Korean Peninsula, transforming the existing bilateral meetings arranged as a side-line to ARF summit into an ad-hoc but important initiative to bring the now-defunct Six-Party Talks outside of Northeast Asia. Cities in Southeast Asia can provide a perfect neutral ground to facilitate talks and dialogues between North Korea and the other powers,” she said in an email reply.

With regards to the ADMM-Plus, she added that it “is another important platform to engage and coordinate among the Southeast Asian states with China, Japan and South Korea to align their security interest and concerns. While the Plus Three members (China, Japan and South Korea) have been playing the assisting roles to the ASEAN member states, it would be a great leap for the ASEAN members to do the same for the Northeast Asian partners.”

Ultimately, ASEAN serves the best interests of its peoples. And unless one is a madman, nuclear warfare is not something the citizenry aspires for. What ASEAN does, at this juncture will be judged in the future – if there is ever one to look forward to.

Recommended stories: