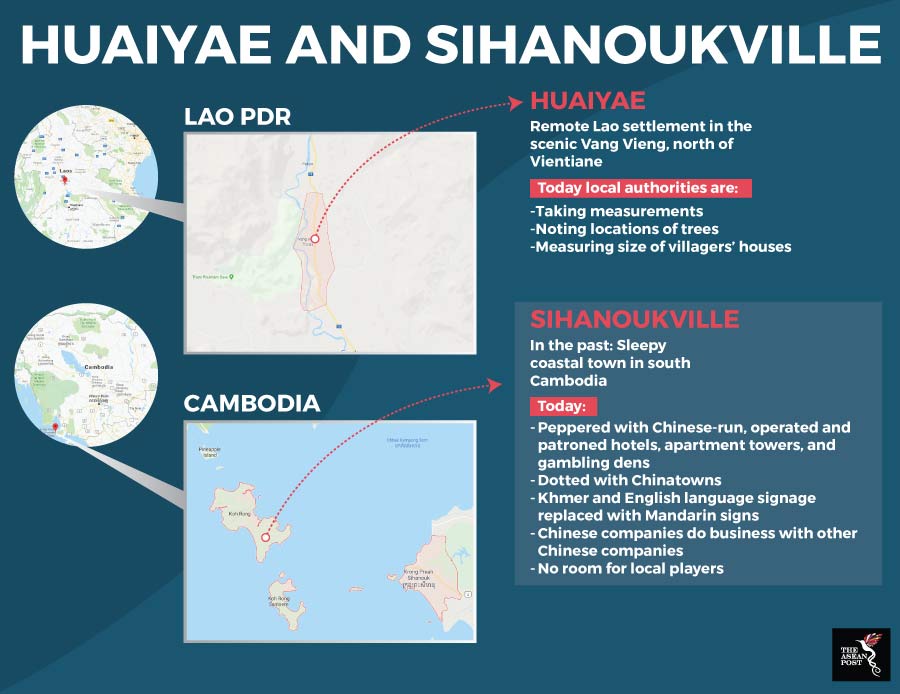

Recent reports have revealed that villagers in the remote Lao settlement of Huaiyae in the scenic Vang Vieng region north of Vientiane have expressed concern about the possibility of losing their land to a Chinese development project. This was after local authorities were spotted in the town taking measurements and noting the locations of trees.

Meanwhile, Vientiane provincial authorities have confirmed there is a Chinese firm looking to develop the Vang Vieng district where Huaiyae sits, but they say that land belonging to locals won’t be touched. Villagers, however, remain sceptical.

Speaking to local media, one of the villagers who refused to be named, claimed that he had also seen authorities measuring the sizes of their houses, adding that no one from the village has signed any documents as yet. Another villager, however, said that some of them had already signed “certain” documents.

It was not revealed what these documents were but there is a possibility that they allude to the selling of the villagers’ houses. A third villager explained that if they were ever forced to sell their land for the project, they probably wouldn’t be properly compensated by the state which could claim that their plots of land were worth much less than they actually were.

The villagers in Lao have good reason to worry, especially considering developments in other parts of the region, especially in neighbouring Cambodia. One area in particular which seems to show signs of the devastation that sometimes comes with Chinese projects – at least for the locals – is the once sleepy, coastal South Cambodian town of Sihanoukville.

China in Cambodia

Sihanoukville was once known for its quiet, cosy beaches. An atmosphere that mostly attracted families, individual travellers, and backpackers. That was until the Chinese investment flooded in, driven by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

By 2018, the once-tranquil city was transformed. Sihanoukville today is an enclave of Chinese investments and is peppered with Chinese-run, -operated and -patroned hotels, apartment towers, restaurants and gambling dens. The area is also dotted with Chinatowns, festooned with neon signs in Mandarin taking the place of Khmer and English language signs.

The magnitude and make-up of its tourists has also changed with the new influx. Tourism increased more than 700 percent between 2012 to 2017. In 2017, Sihanoukville received one million local tourists and 470,000 foreign visitors, of which more than 25 percent were from China. Some of the long-term western tourists living in the city have either been pushed or kicked out to make way for better paying Chinese visitors. Some have moved out or avoid the area because of the loss of tranquillity.

Source: Various sources

Source: Various sources

With the massive influx of Chinese investments, loans, and aid, many observers have cautioned about China’s debt-trap diplomacy. The Chinese loan model, often characterised by opaque contracts, exorbitant interest rates, predatory loan practices, and corrupt deals, has left smaller countries debt ridden and in danger of losing their sovereignty.

The Chinese financial influx is also often ‘closed looped’, with few meaningful opportunities for local players to make money. Chinese companies often do business with other Chinese companies, bringing in Chinese workers. Chinese tourists, often travelling in groups handled by Chinese tourist agencies, want to stay at Chinese-run hotels and eat at Chinese restaurants. Local businesses and people are often forced out of any potential economic gain. The Chinafication of Sihanoukville has also stirred local resentment as more landless Cambodians are pushed out of Sihanoukville development deals as more Chinese workers are brought in to cater to the growing demand.

Unconcerned

Unlike the villagers in Huaiyae, the Lao government remains unfazed by China. In June last year, Lao prime minister Thongloun Sisoulith told the Future of Asia Conference in Tokyo that Lao was unconcerned about the potential debt burden from a Chinese-led high-speed rail project, describing the terms of the construction agreement as "favourable" to one of Southeast Asia's poorest countries.

The prime minister's comments downplayed the risk raised by Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in Beijing back in April. Lagarde had warned that BRI projects could "lead to a problematic increase in debt, potentially limiting other spending as debt service rises, and creating balance of payments challenges" for affected countries.

Thongloun added that given Lao's goal of graduating from least developed country status, it needed to "transform our landlocked country to a land-linked country," and that the high-speed rail project "has been of great importance" to its development.

The high-speed rail link, begun in 2016 as part of China's BRI, will connect Kunming in southern China and the Laotian capital of Vientiane, stretching through other Southeast Asian countries all the way to Singapore.

While Thongloun and the rest of the Lao government might not be concerned about Chinafication, it is obvious that the everyday Laotian is. Looking at what’s already happened to Sihanoukville but also in other parts of the region such as in the Philippines – which is facing a problem with the large number of illegal Chinese workers – it seems that the concerns of Huaiyae’s villagers may be well founded.

Related articles:

The making of new Chinese colonies