The Coral Triangle, a marine region stretching across Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Timor Leste, is endangered by extensive human activities. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), this marine region encompasses portions of two biogeographic regions: the Indonesian-Philippines Region, and the Far Southwestern Pacific Region, endowing it with the world’s richest marine biodiversity.

The Coral Triangle has the highest coral diversity and largest number of coral reef fish species globally, nurturing 76 percent of the world’s coral species (approximately 605 species) and 37 percent of coral reef fish species (approximately 2,220 species).

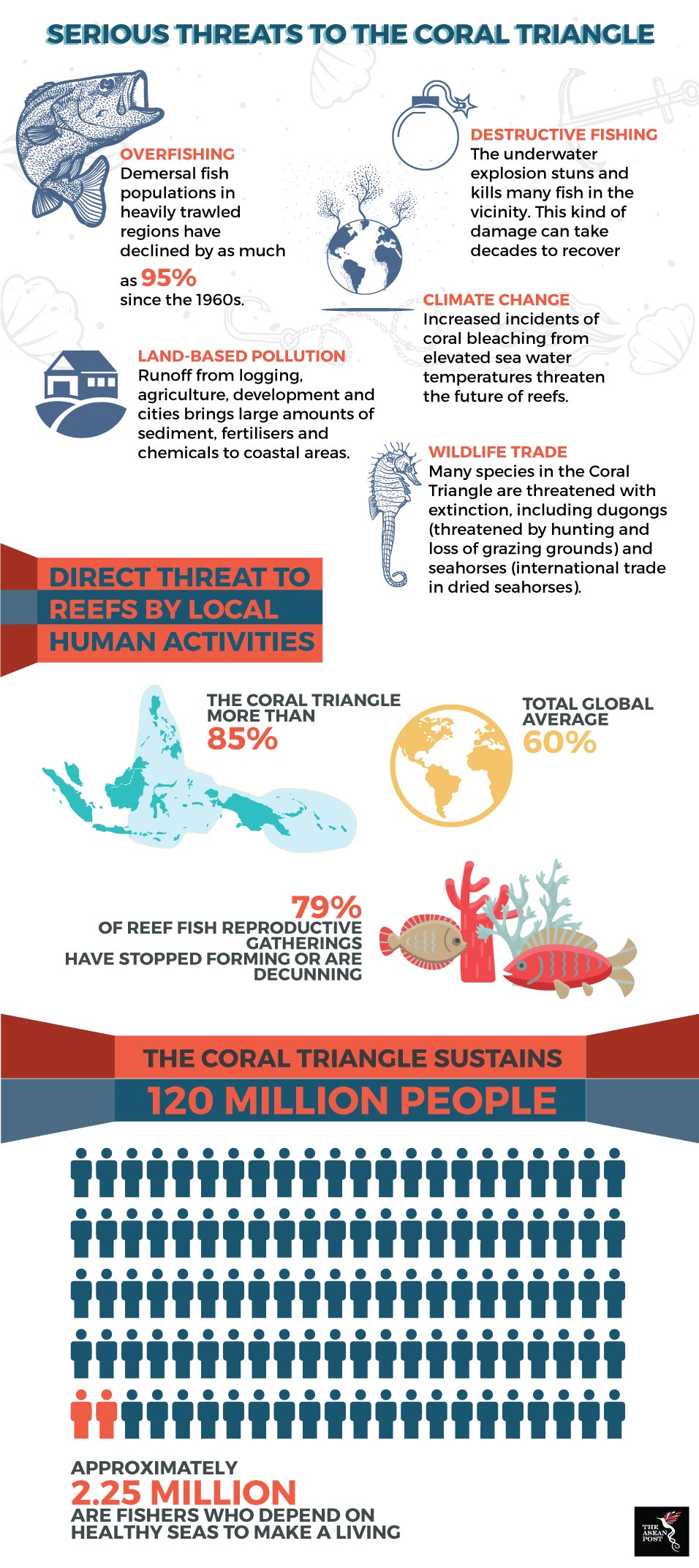

With such high marine diversity, the Coral Triangle sustains at least 120 million people in the region, 2.25 million of whom are fishers who make a living from it. WWF has also stated that the Coral Triangle is an optimal location for tuna nurseries and spawning, which drive the multi-billion-dollar global tuna industry. In addition, coastal communities have been tapping on the Triangle’s natural pull factors, which are valued at over US$12 billion annually in the growing nature-based tourism segment.

Threats faced by the Coral Triangle

Sadly, human greed is the primary cause of environmental degradation in the area, with over-exploitation and destruction of its marine ecosystem having adverse anthropogenic consequences. This is supported by numerous reports and analyses done by international agencies like the World Resources Institute, Asian Development Bank, World Wildlife Fund (WWF), The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the International Coral Reef Action Network (ICRAN), the United Nations Environment Programme - World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC), and the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN).

These reports outline five major threats to the Coral Triangle. First and foremost, overfishing is the most widespread local threat to the coral reefs in the region. which support a fishing industry easily worth up to billions of dollars annually. Species of tuna, shrimp and specific groupers sourced from the area have high demand globally. Hence, bottom-trawling, a method where nets are dragged across the sea floor capturing both, grown-ups and hatchlings, is still prevalent in the region, exacerbating the decline of fish populations, which have plummeted up to 95 percent since the 1960s.

In addition, dynamite fishing, which destroys the ecosystems of regions where it is practised, is spreading like wildfire throughout the Coral Triangle. This destructive method is popular due to the ease in which blasted schools of fish are collected. However, the underwater explosions employed frequently destroy the underlying habitats and reefs supporting local fish populations, leaving only a wasteland of dead coral.

The third major threat to the Coral Triangle is cyanide fishing, a relatively new practice among the area’s fishermen. Cyanide fishing entails the distribution of liquid sodium cyanide into a reef where fish are hiding, stunning them and facilitating subsequent retrieval. Affected reefs are frequently physically damaged during the retrieval process as appropriate equipment is often unavailable, while the sodium cyanide employed poisons living reefs as well.

Climate change and disrupted weather patterns are the fourth major threat to the Triangle, increasing the incidence of coral bleaching from elevated sea water temperatures. The rise of temperatures and seawater acidity worldwide threatens the global ecosystem as whole, while disrupting the balance of the world’s marine life.

Aside from that, rapid urban development has increased the scale of logging activities across the board, which directly contribute to deforestation and forest degradation. This in turn flushes large amounts of sediment, fertilisers and chemicals to coastal areas, altering the pH value of seawater while feeding uncontrollable algal blooms on reefs which compete with existing coral populations.

Finally, six out of seven of the world’s marine turtle species, including the leatherback and green turtle, can be found in the Coral Triangle. However, these are now facing extinction, even though local authorities have taken steps to control and eradicate wildlife trade in the area. Turtles are hunted for their eggs, shells and meat, which fetch high prices on the black market. To make matters worse, land-based pollution is destroying turtle nesting beaches in the region.

Conscience as the key

International and local authorities like the WWF have launched various campaigns, strengthening and enforcing fishing regulations in the Coral Triangle, yet these steps seem to be ineffective in raising awareness among the public regarding the importance of Southeast Asia’s marine ecosystems. ASEAN should consider addressing this issue, perhaps through multilateral accords similar to how the United Nation Framework Convention Centre (UNFCC) initiated the Paris Agreement in 2016 to counter climate change.

Lack of media coverage and information about the extent of damage to coral reefs in the region are also concerns, highlighting a focus on diplomatic policy at the expense of fundamentals such as environmental sustainability.